ESG steps forward in rating-agency analysis

The global green, social and sustainability (GSS) bond market grew to more than US$200 billion of aggregate issuance in calendar 2018 without developing a specialist niche for the main international rating agencies. While the majority of GSS transactions come from rated issuers, only a relatively small proportion have a rating-agency contribution to their GSS aspect.

Laurence Davison Head of Content and Editor KANGANEWS

The global green, social and sustainability (GSS) bond market grew to more than US$200 billion of aggregate issuance in calendar 2018 without developing a specialist niche for the main international rating agencies. While the majority of GSS transactions come from rated issuers, only a relatively small proportion have a rating-agency contribution to their GSS aspect.

For instance, Environmental Finance data suggest about 11 per cent of GSS deals completed in 2018 had an external review completed by either S&P Global Ratings (S&P) or Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s), while Fitch Ratings (Fitch) was not active in this space. For comparison, the market leader in 2018 – Sustainalytics – provided external review on nearly 20 per cent of GSS bonds.

External review is a crowded field and the traditional rating agencies are staking their claim to market share. But it is the emergence of entity-level – rather than transaction-specific – ESG analysis and scoring that allows rating agencies to deploy their expertise in ESG risk analysis as part of their core business offering.

The rating-agency sector is rapidly moving toward ESG being a fully integrated component of credit analysis, and the pace of evolution is quickening as the time horizons for climate risk, in particular, become increasingly relevant to debt investors. All three main rating agencies say investor demand for this evolution has picked up in the last year or two.

Fitch made a notable move in this space in 2019, by incorporating ESG scoring into all its mainstream credit reports. It describes itself as “the only rating agency at the moment that transparently displays the relevance and materiality of ESG issues in all the ratings we release”. Moody’s and S&P are far from absent from the ESG space, though. Both have updated the contribution ESG factors make to their overall rating process.

The biggest challenges to full incorporation could be the difficulty of assessing materiality over a medium-term timeframe – especially when public policy is volatile or not fully formed – and the availability and consistency of disclosure.

ESG inclusion rationale

All three rating agencies say their moves to greater incorporation of ESG into the mainstream rating process are driven primarily by an increasing understanding that these factors can provide material financial risks in a meaningful timeframe.

For instance, while S&P has been thinking about ESG issues in credit analysis for at least the last 8-10 years, its Sydney-based senior director and sector lead for Pacific corporate and infrastructure ratings, Richard Timbs, says the impetus has clearly grown. He tells KangaNews: “Over time, as there has been more evidence about climate change and evolution of social and community expectations, the impact of environmental and social factors on credit has become more regular and more pronounced. For instance, climate-change events are happening more frequently and the impact of these events is more severe.”

S&P did a study in 2018, covering the period June 2015 to June 2017. This looked at a sample of about 7,500 global corporate credit ratings and identified occasions when a credit review or report referred to ESG. The study found that about 15 per cent of the sample had some form of ESG factor and in about 3 per cent of cases an ESG issue was an explicit driver of change in a rating or outlook. About 60 per cent of the changes were negative.

Of the 15 per cent, Timbs says slightly more than half were references to the environment. Within the 3 per cent that were explicit rating drivers, again, half were environmental and about a third related to governance.

Investor demand

The materiality of ESG risk is climbing. It is no surprise rating agencies are also experiencing buy-side demand for more, deeper, more quantifiable and better-embedded ESG analysis. Following a trip down under in July 2019, Andrew Steel, global head of sustainable finance at Fitch in London, told KangaNews the catalyst for integrating ESG analysis into its rating process came from the UN Principles for Responsible Investment’s initiative for ESG in credit risk and ratings.

This aims to enhance the transparent and systematic integration of ESG factors into credit-risk analysis. “The message that emerged loud and clear was that rating agencies were not displaying subcategories of risk sufficiently clearly,” Steel said.

Fitch then spent several months in consultation with asset managers globally to try to ascertain whether they would like to have this information on a permanent and ongoing basis. Steel continued: “We quickly reached the conclusion that calls for this data were not a fad, rather the data forms part of asset managers’ requirements and will continue to do so.”

There is some debate about whether investor demand for rating agencies to present ESG analysis in their mainstream process is as prevalent in Australia as in, for instance, Europe.

Steel told KangaNews his impression was that Australia’s buy side is more focused on product, including GSS bonds and sustainability-linked loans, whereas investors globally are further progressed with embedding ESG analysis holistically.

On the other hand, Ilya Serov, associate managing director, structured-finance group and chair, Asia-Pacific ESG working group, at Moody’s in Sydney, says: “When I got involved in the ESG field three or four years ago, ESG-related questions from investors came up only infrequently and tended to be pretty high-level. We are now at a point where I’d say probably the majority of investor conversations have an ESG component to them and every organisation we deal with is engaged with the topic.”

How to deliver ESG analysis

The way rating agencies deliver ESG analysis varies between the providers. But there are common themes. Naturally enough, the focus is always on risk factors and rated entities’ planned response to them. The rating agencies have generally elected to view this through both a sector-level and an entity-specific lens.

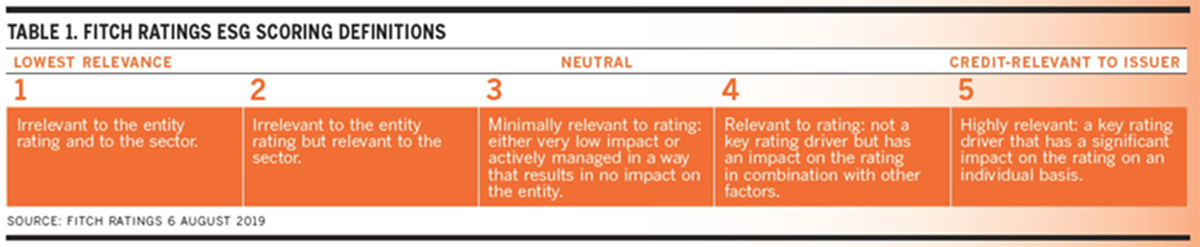

Fitch, for instance, reports ESG risk on the basis of a 1-5 score that incorporates sectoral and entity factors (see table 1). Of the first 73,000 individual ESG scores Fitch published – on more than 5,300 publicly rated entities – between January and June 2019, 22 per cent of corporate entities had at least one score of four or five. “This confirms that, from a credit perspective, ESG risk factors are important and material to credit ratings,” Steel told KangaNews.

Moody’s works down from its own ESG taxonomy, to sectoral risk analysis – including estimating the timescale on which risk factors will emerge – to issuer-level assessment.

Moody’s has also introduced a specific carbon-transition assessment that ranks issuers on a 1-10 scale – with 1 being the best outcome and 10 the worst – where scores increase as individual entities’ ability to deal with regulatory and other environmental risks weakens.

In November 2019, Moody’s published the results of its carbon-transition analysis of the global automobile manufacturing sector. The median score was CT-6 – slightly below expected average – but Serov says the range of outcomes demonstrates the value of this type of analysis.

S&P looks at business risk profile, including industry risk, alongside specific financial risk factors for an issuer. The first part of this is the industry generally. S&P has been through an exercise of assessing and ranking sectors based on their exposure to environmental and social risks. It then tries to make an assessment of an issuer’s exposure to environmental or social issues relative to its peer group.

“The other area we assess is the financial risk profile,” Timbs explains. “Where we can make a reasonable assessment into the foreseeable future, we are looking for potential cash-flow impact – good or bad – from specific environmental or social reasons. It is a bit harder to make a material judgement on the social side.”

In November 2019, S&P acquired the ESG ratings business from RobeccoSAM. This includes the SAM corporate sustainability assessment (CSA) – an annual evaluation of companies’ sustainability practices. S&P says the CSA is “recognised as one of the most advanced ESG scoring methodologies, as it draws upon 20 years of experience analysing sustainability’s impact on a company’s long-term value creation.”

Timing challenges

The idea of a reasonable assessment into the foreseeable future speaks to the biggest challenge in ESG analysis as part of the rating process: judging the amount of time before a risk factor becomes material. Timing risks is important in any credit analysis, of course, but environmental and social risks are particularly time sensitive.

This also explains why the equity market has been quicker than fixed income to embrace ESG integration. Equity investors have a perpetual exposure and should therefore consider all factors material to future earnings. Debt investors have a fixed horizon for capital return and can, in theory, ignore risks that do not become material during their exposure period.

Timbs says some debt investors have started thinking about ESG risk from a long-term-hold perspective – they look through future refinancing, in other words. Others have a shorter-term focus. They might be thinking no further than whether an issuer will be able to get its next refinancing away and whether ESG considerations could have an impact on its ability to do so.

“We don’t have a hard-and-fast time horizon when we are doing a corporate credit rating,” Timbs reveals. “Some market users seem to assume it is three years, and this isn’t a bad guideline. But it’s still not accurate – it could be two years or it could be four or five. It’s really about the level of confidence we have about risk and cash flow over the period of time we are analysing.”

The position is similar for Moody’s. Serov explains: “The rule is generally that there is no fixed rule – we will consider anything we think could affect a company’s credit position. This also means we have no set time horizon, be it for ESG or any other factor.”

The challenge is that the further out analysis goes the harder it becomes to assess materiality. Serov continues: “We try to incorporate anything where we think there is sufficient visibility and certainty, even if it is a long-term factor. We give most value to factors on a 1- .to 5-year horizon but there is some weight given in the Moody’s scorecard to 6-15 years and beyond.”

Fitch’s approach is slightly more proscriptive. Steel told KangaNews that the “vast array” of ESG rating products, from more than 220 providers, are based on a range of very different time frames. But he added: “This can be confusing for asset managers as they try to work out the relative importance of different factors. To provide consistency, we decided to match our scores with our rating time frame – typically a 3-5 year forecast period.”

Adding to the complexity is the fact that public policy can have a massive impact on the level of risk ESG factors pose to issuers. It is easier to assess an energy company’s planning around emissions transition if it operates in a jurisdiction with a coherent energy policy and a well-established carbon-trading scheme, for instance.

“It is extremely difficult to factor in the vagaries of public policy, and in some cases it is not really possible at all,” Timbs comments. “Australian energy policy is a good case in point. It has been fluid for many years and still isn’t really clear now. It is extraordinarily difficult to build judgements about policy and pricing into the future or estimates of when certain impacts might occur into a credit assessment.”

Serov says “by far the biggest challenge” for ESG analysis is the relevance and quality of data and disclosure. “There are big questions about standardisation and consistency of disclosure across asset classes and jurisdictions. We are grappling with this, because of the extent to which we base our views on public data.”