Before the deluge

In mid-October, the EU embarked on a funding programme so large that European market participants say it could reshape the European market and have ripple-effect consequences for others. There is no suggestion that the supply cannot be digested by the euro market, but other issuers may adjust their funding plans around the EU’s jumbo issuance forecast.

Matt Zaunmayr Deputy Editor KANGANEWS

On 19 May, the European Council adopted the Support to Mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE) regulation. This is designed to provide loans to EU member states to help fund programmes designed to preserve employment during the COVID-19 crisis.

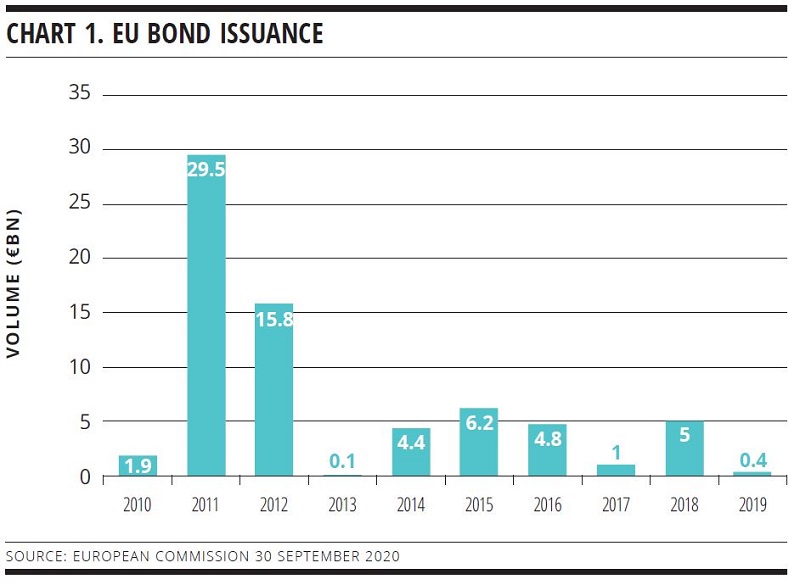

By the end of September, the EU had approved €87.4 billion (US$102.9 billion) of loans to 16 member states. The programme has a current limit of €100 billion that will be funded in the euro debt market. This marks a step-change in issuance for the EU, even compared with its previous period of emergency funding around the Eurozone sovereign-debt crisis (see chart 1). The EU’s borrowing programme is arranged by Crédit Agricole.

The EU’s first foray into the bond market under its new issuance mandate suggests appetite is ample to say the least. The first SURE transaction priced on 20 October, raising €17 billion (US$20 billion) in 10- and 20-year tranches from a staggering book of more than €233 billion.

All the EU’s SURE funding will be compliant with the EU’s social-bond framework, which aligns with International Capital Market Association’s Social Bond Principles.

EU transactions will range in maturity from three to 30 years, with amounts due in any given year not to exceed €10 billion. SURE loans will have a maximum average maturity of 15 years.

SURE funding will be in addition to the EU’s existing funding requirements. The macrofinancial assistance (MFA) programme will raise €3 billion aggregate in 2020 and 2021, of which €160 million has so far been raised. The European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM), meanwhile, has a requirement of €9.8 billion in 2021 to lengthen expiring loans to Portugal and Ireland.

The EU officially has until the end of 2021 to raise what is expected to be the full €100 billion of the SURE package. However, given most of it is already subscribed to, the consensus in the market is that it will seek to raise it by the middle of 2021.

KangaNews understands the EU indicated on a global investor call in July that it plans to be in the market roughly every second week, though it will not have a specific issuance calendar.

PRICING THE DELUGE

How the market – including other supranational, sovereign and agency (SSA) sector issuers – responds to the influx of EU paper will be a subject of keen interest, in Europe and elsewhere.

The EU currently prices wide of French and German sovereign bonds. Florian Eichert, head of covered bond and SSA research at Crédit Agricole in Frankfurt, tells KangaNews the EU was in a good place ahead of its its new deal on the back of significant widening in the French government sovereign curve in recent weeks. He adds that the EU was trading 5-6 basis points wide of the French government 10-year bond and would likely need to add a further 5-7 basis points for its inaugural deal.

What happens after the debut is debatable – and market participants are not yet sure whether EU supply will pull the market wider or have the opposite effect. Stuart McGregor, managing director and head of European SSA debt capital markets at RBC Capital Markets in London, points out that one reason the EU trades wide to France is its lack of issuance volume and thus liquidity. This will not be the case for much longer.

“There is a school of thought that having another benchmark issuer in the market could attract more interest. Having more liquidity in euros could attract more foreign reserves and more international attention. In this scenario, EU pricing could actually tighten,” explains McGregor.

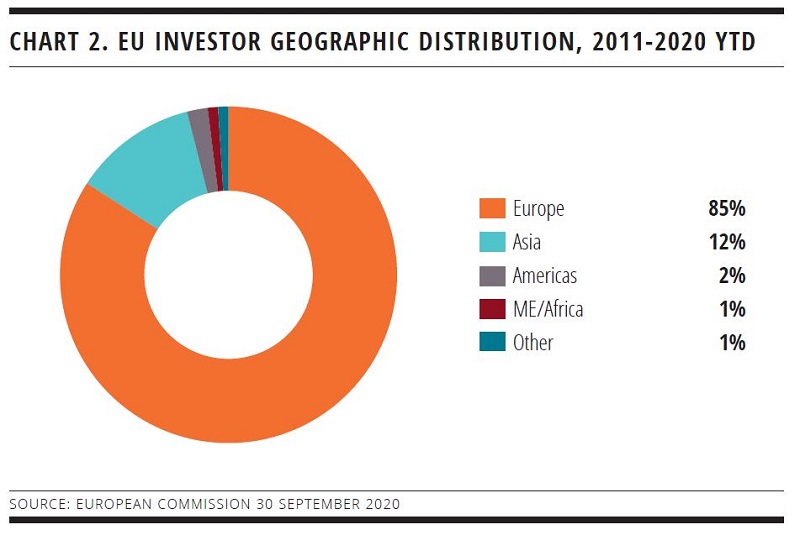

The geographic investor distribution of EU bonds from 32 benchmark transactions between 2011 and September 2020 was overwhelmingly European (see chart 2).

The liquidity of the EU curve will be crucial to attracting offshore central-bank and official-institution investors, comments Eichert. “If the EU manages to price large and liquid benchmarks, I think non-European investors will start to look at the EU as a partial substitute for some of the smaller European government-bond markets. However, if the EU ends up pricing a lot of €3-5 billion benchmarks, in line with other supranational names, this will not materialise.”

Mark Byrne, syndicate at TD Securities in London, agrees that scaling up the EU programme will not necessarily mean spreading the same investor dollars across more supply. In fact, he believes, the market as a whole will grow as the EU will crowd in investors.

While more global investor participation would help, Byrne adds that existing investors in European government and SSA bonds are currently showing strongest interest.

There are further complicating factors for the direction of EU pricing. On the positive side for the EU, SURE loans could ease individual sovereign funding needs and lead to better performance for some European sovereign bonds. “When Italy and Spain trade well, it gives an overall positive tone to European credit,” says McGregor.

Conversely, investors will be aware that the SURE programme will be followed by the Next Generation EU package to fund the region’s COVID-19 recovery. The EU estimates this will require around €800 billion from 2021-26, with front loading expected in the first three years.

There is no doubt among European bankers that liquidity conditions in Europe and around the world are sufficient for markets to swallow the initial SURE programme.

The European Central Bank’s repo operations are creating demand for high-quality liquid assets and by October euro high-grade markets were trading at their tightest levels since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis.

Eichert tells KangaNews the makeup of the EU’s ongoing buyer base will depend on the maturities the issuer targets. “There is more than €3 trillion of excess liquidity in the eurozone banking system so bank treasuries will jump on 10-15 year issuance with pricing above France. Long-end EU pricing that is flat or slightly positive to France will find asset-management and insurance demand.”

The market may be replete with liquidity at the moment but multiple years of €100 billion-plus EU funding requirements will be the true test of appetite. Byrne says the depth of the European market means the volume of issuance will be manageable, although it may attract a premium at some points and under certain market conditions.

He adds that ongoing QE in Europe, which unlike other markets includes SSA borrowers, will play a key role in the EU’s funding programme. The European Central Bank, under one or more of its raft of QE programmes, has capacity to purchase 50 per cent or more of European supranational bonds in the secondary market and therefore provides a powerful support mechanism in more challenging conditions.

TRICKLE DOWN

Floods can often be a benefit to regions downstream, away from the main impact area. This may be the case in the Eurozone bond market as the consequences of the EU’s turbo-charged funding flow through capital markets. The short- and long-term effects on the funding plans and pricing of other European borrowers, particularly SSAs, could be large.

While €100 billion of EU funding per year will not mean an equal amount of issuance by other borrowers being displaced into global markets, there is no doubt some trepidation around what the EU’s plans mean for Europe’s other large borrowers.

Major SSA names like European Investment Bank and KfW Bankengruppe already typically raise around €65 billion each per year. Eichert says these issuers have tried to get as much as possible of their 2020 funding done before the EU enters the market. However, he adds that beyond 2020 borrowers have few options other than to take market conditions as they come.

The end of the year is often quiet for SSA issuers, before they come out aggressively in the new year. However, McGregor says it would not be surprising to see both periods busier than usual given the circumstances.

He tells KangaNews that with SSA pricing currently at tight levels those that can pre-fund for next year may take the opportunity to do. He adds: “There are so many unknowns and so much money to be raised by governments globally that SSAs may come out even more eagerly at the start of the new year.”

Only a few markets provide benchmark-volume deals for SSAs, with euros and US dollars being the mainstays while Australian, Canadian and New Zealand dollars, sterling and the Nordic currencies usually account for most of the remainder.

While SSA access to the euro market may not be hindered, the price they can fund at may need to change – particularly if they are competing with the EU for a similar buyer base. Byrne explains: “If the EU is consistently offering a new-issue concession investors may start to require similar for all new transactions.”

Eichert says the level at which the EU is expected to begin funding would not necessarily cause other issuers’ secondary pricing to move. However, if other benchmarks, such as the French sovereign, begin to show signs of volatility, this could shift the EU and other SSA pricing wider.

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.

SSA Yearbook 2023

The annual guide to the world's most significant supranational, sovereign and agency sector issuers.