Australian credit changes shape

The Australian dollar credit market has been reshaped in the wake of COVID-19, largely as a consequence of Reserve Bank of Australia market intervention. A supply-demand imbalance is evident and could potentially bring risk, but fund managers express a degree of comfort on the basis that their approach to allocation has not yet needed to change dramatically.

Matt Zaunmayr Deputy Editor KANGANEWS

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) implemented the first phase of its emergency response to the COVID-19 crisis in March last year. Its interventions have directly influenced the whole Australian dollar fixed-income market.

Government-bond purchases – whether for yield-curve control (YCC), market function or QE purposes – have supported a record-smashing level of sovereign issuance, while on the other hand the term funding facility (TFF) has essentially eliminated the primary source of Australian dollar credit: senior-unsecured supply from domestically domiciled banks.

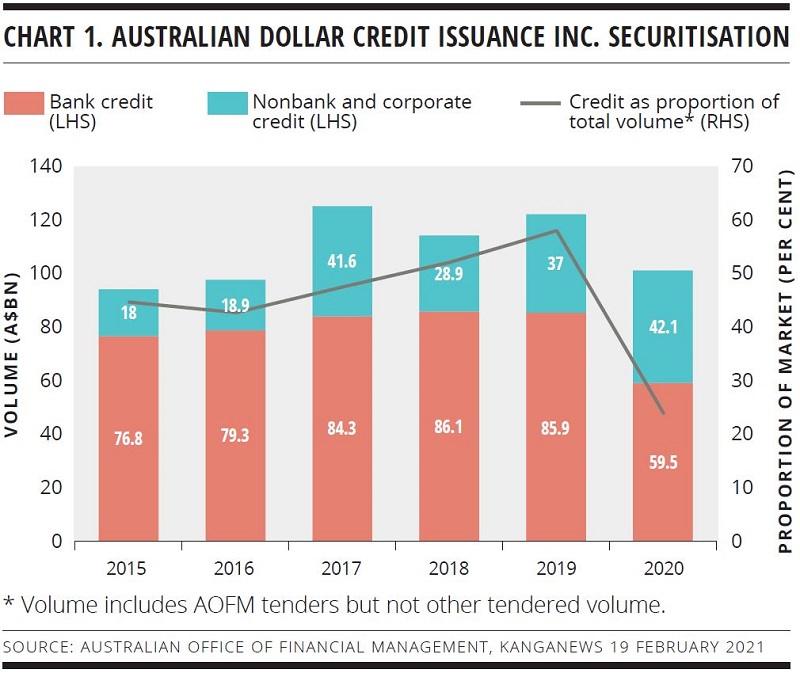

The headline result has been a decline in aggregate credit supply in the Australian dollar market and, factoring in the sovereign-sector issuance boom, an even bigger fall in the credit proportion of total issuance (see chart 1).

The raw numbers do not tell the whole story of a profoundly reshaped market. For example, the volume of government and semi-government bonds taken out of the market by the RBA – A$134.5 billion (US$105.2 billion) by 19 February 2021 – is not reflected in the figures, nor are moves made by investors in response to the all-time-low rates environment, for instance out in tenor or down the credit spectrum.

It is therefore somewhat surprising to find that fund managers say the market ructions of the last year have not drastically altered their credit strategies.

STATE OF PLAY

The RBA’s bond buying, particularly since it added pure QE to its YCC and market-function mandates in November 2020, has created a technical tailwind for high-grade bonds.

Tim van Klaveren, head of Australian fixed-income portfolio management at UBS Asset Management in Sydney, says RBA intervention is at the margin forcing investors out along the yield curve and down the credit spectrum. “The margin for semi-government and SSAs [supranationals, sovereigns and agencies] over ACGBs [Australian Commonwealth government bonds] in any shorter-dated line is razor thin. For semi-government bonds, you need to go beyond 10 years to get a pickup.”

RBA buying has aligned with the gradual reduction to the committed liquidity facility (CLF) available to bank asset-liability management (ALM) books, adds Tim Hext, portfolio manager at Pendal in Sydney. With more government and semi-government bonds – Australia’s only qualifying high-quality liquid assets – on issue, banks are expected by regulators to hold more of these securities for their ALM needs. Hext says this growth has virtually matched the increase in semi-government funding requirement.

More issuance does not necessarily mean more free float of bonds, however. Hext says the RBA’s extension of QE, announced in February, means it will likely be buying more government bonds from the market over the next eight months than the government will supply.

For investors traditionally weighted toward the high-grade sector, this environment has provided opportunities. Nikko Asset Management’s Sydney-based head of Australian fixed income, Darren Langer, tells KangaNews there are more opportunities for fund managers to find relative value in the semi-government market now than has been the case for many years.

If banks and the RBA are structurally set to absorb incremental sovereign and semi-government supply – especially as these issuers’ funding needs start to subside once more – it would seem inevitable that the skinny state of credit supply will pose a challenge to local investors.

Demand for credit deals has indeed been very strong since the return of primary issuance in the second half of 2020, particularly so in the deals that have come so far in 2021.

Columbus Capital’s residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) deal on 10 February, Suncorp-Metway’s senior-unsecured transaction on 16 February and Charter Hall Long WALE REIT’s senior-unsecured deal on 22 February all printed with tight margins – the latter even as the 10-year ACGB widened by around 15 basis points on the day.

The trend for well-bid credit deals looks set to continue as long as the RBA maintains its QE programme. “If the RBA buys another A$100 billion of bonds this needs to be recirculated somewhere. This is pushing investors into credit or into equities if they have multiasset funds. Corporate and financial-institution borrowers will be the beneficiaries,” explains van Klaveren.

CREDIT CONUNDRUM

Reallocating investable funds away from the safe haven of government debt and into higher-yielding credit instruments is an intended consequence of any central-bank asset-purchase programme. The specifics of Australian QE – particularly the existence of the TFF – potentially cause some problems for investors, though.

The TFF and a surge in bank deposits sparked by COVID-19 have eliminated most banks’ needs for senior-unsecured funding – traditionally the largest source of credit in the Australian dollar market. Suncorp’s February deal was just the third benchmark in the format from an Australian domiciled bank since February 2020.

There are some preliminary signs that senior-unsecured supply may return to some extent in 2021 – perhaps to a greater degree than was expected even at the end of 2020 – as surging housing demand and household savings drawdowns point to an economic rebound and bank-credit growth. The latter rocketed to nearly 20 per cent in early 2021 from 6 per cent in the June quarter last year. The RBA also confirmed in February that the TFF would end as planned on 30 June.

The outlook remains unclear, though. For one thing, bank issuers themselves have repeatedly emphasised that they do not expect their wholesale funding tasks to rebound to anything like the pre-pandemic level even when the TFF is no longer available. A quicker-than-expected credit-growth rebound could change this picture but investors say they are not working on the basis that the banks will be back in size in the short-to-medium term.

Hext says: “We expect the scarcity of bank paper to last into 2022. However, markets are forward-looking and if credit growth begins to pick up it is possible that banks will be back in the market, particularly given where credit spreads are at the moment.”

With bank issuance likely to remain subdued in the near term, adding credit to portfolios may be difficult. Corporate and nonbank issuance rose in 2020, but in nothing like sufficient volume to offset the absence of senior bank supply. In fact, nonbank credit issuance arguably outstripped reasonable expectations. Cash-rich, asset-hungry banks are competing hard with the capital market for new supply in an economic environment that was far from supportive of widespread capex.

Instead, after a period in which borrowers turned to their banks first to shore up liquidity against the incoming crisis, the second half of 2020 was busy in corporate and nonbank funding.

In the Australian dollar corporate market, busy years are often followed by leaner ones as many borrowers front-load refinancing to take advantage of benign conditions. In securitisation, the larger, programmatic nonbanks will need to fund, but the busy finish to 2020 has likely contributed to a slow start in 2021. Furthermore, competition for mortgages intensified during 2020, potentially putting pressure on nonbanks’ origination growth.

All this means the theme of demand outstripping supply in the credit sector is likely to continue. Pauline Chrystal, portfolio manager at Kapstream Capital in Sydney, tells KangaNews the dynamic is clearly evident in the secondary market. “Secondary liquidity is very good when we are selling but not when we are buying. We have not bought much in the secondary market – we are waiting for primary supply.”

Eyes on inflation

Central banks, including the Reserve Bank of Australia, have reinforced commitments to QE and ultra-low official rates for the foreseeable future. However, in 2021 theoretical discussions about inflation risk have turned into somewhat louder rumblings, leading investors at least to consider what central-bank policy tapering might herald.

Australian Commonwealth government bond (ACGB) and other government bond yields have inexorably marched higher since the beginning of 2021 – the 10-year by around 70 basis points from early January to late February. Furthermore, as of late February the overnight indexed-swap curve was predicting a cash-rate increase to 0.25 per cent in late 2022.

There are multiple drivers, including the exposure of long-end rates to global central-bank policy and positive COVID-19 vaccine news since the end of 2020 putting a tailwind behind global economic recovery.

One hypothesis gaining momentum is that the quantum of stimulus injected into the global system over the last 12 months, combined with reopening of economies, could cause an inflation shock and possibly lead to central banks raising interest rates or tapering QE programmes sooner than expected at the start of 2021.

RISKY BUSINESS

The potential risks for the Australian credit market are twofold. First is the impact of an increasingly primary-market, buy-and-hold environment on reliability of pricing marks and general functionality. Perhaps of even more fundamental concern is the chance that substantial volume of Australian dollar investment funds will migrate offshore if it cannot find sufficient supply of suitable assets at home.

However, fund managers say they are comfortable on both issues – so far. Langer says a primary-market focus is nothing new for the Australian market, for instance.

Meanwhile, foreign-currency allocation is certainly an option for fund managers but not one many expect to take up widely due to the process of approvals typically required. “For most investors, any change in currency allocation requires approval and documentation change. It is probably easier for most to remain in Australian dollars and look at different asset classes,” Chrystal tells KangaNews. However, she adds that Kapstream itself expects to use a greater proportion of its funds internationally.

Van Klaveren points out that offshore credit markets are not necessarily a better option at this point in the cycle, despite their depth. “We are less keen on offshore investment-grade credit because of the longer duration of these indices in a rising interest-rate environment. US investment-grade index duration is around nine years – much longer than the Australian credit market.”

For now, fund managers appear more concerned with watching the near- and medium-term risks of inflation, interest rates and QE tapering.

POSITIONS NEW AND OLD

Despite the challenging supply environment, record tight credit spreads and a still-uncertain economic backdrop, fund managers tell KangaNews they are not applying radical changes to their allocation strategies. Chrystal points out that tight credit spreads is not a new phenomenon. The market was having a similar discussion at the start of 2020, and all that has really changed is that valuations are now even tighter and the macro backdrop weaker.

Langer adds that the composition of the Australian dollar bond index has been trending toward a very heavy weighting of government bonds over credit for several years. He says Nikko’s weighting to credit has remained consistent and it has not had problems gaining exposure, though he acknowledges that the situation may be more challenging for larger accounts.

Even some of Australia’s biggest credit managers say the market is still functional, though. Adrian David, division director at Macquarie Investment Management in Sydney, says his firm is still able to be selective on a sector and name basis. “We are looking at single-name opportunities. These are typically within sectors that were more affected by the COVID-19 crisis and have yet to fully recover but should do as the economy picks up again,” he explains.

Several investors name securitisation as a sector that retains value. Senior bank and nonbank RMBS margins lagged significantly behind the tightening of other credit spreads in the second half of 2020. The gap may be closing. The 10 February deal from Columbus printed at 85 basis points over one-month bank bills, significantly tighter than the equivalent tranche in Resimac’s 4 December deal, at 120 basis points over bills. Asset managers say there is still value in securitisation despite a degree of correction in 2021, though.

To put this in perspective, on 22 February UBS Australia launched a five-year senior-unsecured deal with indicative price guidance of 55 basis points over swap and BNP Paribas began marketing its own senior nonpreferred transaction with a 5.5-year call date at 100-105 basis points area. On the same day, major-bank senior bonds were marked at around 38 basis points over swap on Yieldbroker ratesheets.

Some investors have also diffused into other parts of the financial-institution market. For example, Hext says it has been a happy coincidence for banks that, despite the suboptimal macro circumstances, their senior-funding needs have evaporated while they are taking on a much-increased tier-two task.

“Tier-two bank paper has become almost akin to what the senior bank market was before COVID-19. It has the greatest volume of new supply and secondary turnover, because investors that previously would not have looked at it are now forced to,” Hext explains.

Meanwhile, Chrystal says Kapstream’s strategy has involved cycling through the various parts of the financial-institution market, including to regional banks from major banks, and then into international bank senior and subordinated paper where a substantial pickup to major-bank paper and somewhat frequent supply are still available.

Chrystal says the result of Kapstream’s strategy is that its overall allocation to financial institutions is lower but not drastically so, at around 30 per cent now compared with 40 per cent a year ago. The rest is invested in different currencies and asset classes, including corporate paper and RMBS, she adds.