The scale of the task

The importance of decarbonisation to the Australian economy is now almost universally accepted. The remaining questions surround whether it can be achieved quickly enough and the scale of costs and benefits deriving from the pace at which transition is achieved. National Australia Bank has published detailed research on the size of the task at hand and is showing how it feeds down to decisions taken with major customers.

Laurence Davison Head of Content KANGANEWS

“Decarbonisation of Australia’s economy is inevitable,” states a major report conducted by Deloitte Access Economics and commissioned by National Australia Bank (NAB), All Systems Go: Transforming Australia’s Economy to Grow. Published in July this year, the report endeavours to put a monetary value on positioning Australia’s economy for growth in a low-emissions world – or the failure to do so.

The numbers are enormous. The report estimates that coordinated, early action toward decarbonisation could be worth A$890 billion (US$579 billion) to the Australian economy over the next five decades.

If no additional or significant climate action is taken, the cost could be A$3.4 trillion over the same period – roughly six times the economic contraction seen during the lockdown year of 2020, annually, for 50 years.

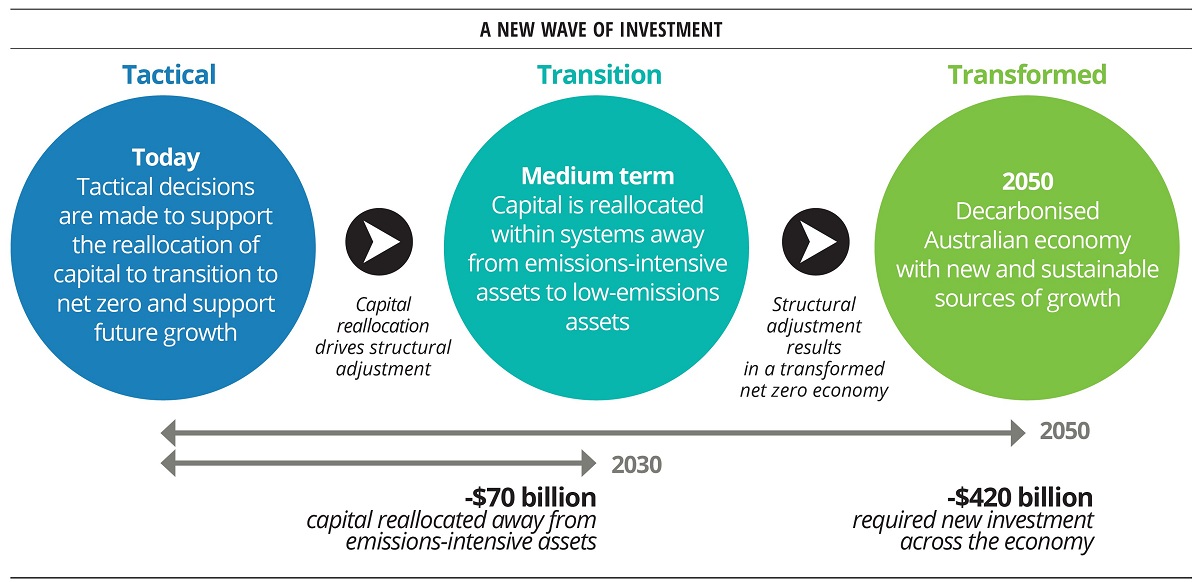

The volume of capital required to navigate a course to the best-case scenario from the worst is also substantial. The Deloitte-NAB report estimates that A$70 billion of investment could be reallocated from emissions-intensive industries over the coming decade, while at least A$420 billion of new investment is required to build a competitive, net zero economy by 2050 (see chart).

Of the new investment figure, the report identifies A$200 billion of “enabling services” investment that falls under the headings of energy, mobility, raw materials manufacturing, and food and land use. As two case studies from NAB’s institutional bank show, this can mean investment in major strategic change for businesses in these sectors, in the short and longer term.

A capital reallocation of this magnitude will also require efforts that stretch across markets. NAB is working to open doors for the allocation of capital toward environmental transition to new groups of investors.

Source: Deloitte Access Economics July 2022

View from the top: taking up the great climate transition opportunity

Australia knows its sustainable future depends on transitioning to net zero by 2050. But it is the actions we take right now as a country that will put us on a trajectory for success and create the greatest long-term dividends, says David Gall, group executive, corporate and institutional banking at National Australia Bank in Melbourne.

The energy transition is now a matter of urgency. Before we know it 2050 will be here, and 2030 is even closer. Today’s world of sustainable finance clearly has a critical role to play in helping catalyse the depth of change required to get us there in time.

Helping customers evolve is a core part of banking. But it is not often we get to chart a course of action that takes in such a significant shift across the whole economy over three decades.

Make no mistake. While the full impact will be felt in the years to come, it is the investment decisions we make today, as a nation, that will be crucial to achieving a successful trajectory.

This is what makes working with some of Australia’s largest organisations here at NAB so exciting, as we see the sort of opportunities and innovation the climate transition is bringing.

This tremendous change and opportunity is the focus of recent NAB research with Deloitte Access Economics, which helps quantify what a great reallocation of capital this decade can bring.

Our report, All Systems Go: Transforming Australia’s Economy to Grow, shows the nation will already be investing A$20 trillion to 2050 regardless of any transition plans. But it is through changing how we deploy this capital to enable a low-emissions future that will add up to substantial economic gains and a positive uplift for the environment.

Importantly, the research shows that if coordinated and early action is taken toward decarbonisation, the Australian economy stands to gain around A$890 billion over the next 50 years – compared with A$3.4 trillion in potential economic losses over the same period if no action is taken.

Put simply, the more we do for the transition today, the greater the long-term dividends for business and our community. It is change we can afford to do and must do.

The nation will need greater co-investment and collaboration from business, government and industry in low-emissions technology and in developing further solutions for hard-to-abate sectors. We must make the necessary, urgent adjustments today, while taking a long view in reviewing and learning as we go.

SUSTAINABILITY LEADERS

At NAB corporate and institutional banking, we recognise this urgency and opportunity, and are already moving to be a catalyst for change. We have been sustainable finance leaders for almost two decades and are well placed to help our customers and communities do what needs doing.

We remain at the vanguard of the development of green, sustainable and social bonds, environmental, social and governance (ESG)-linked derivatives, sustainability-linked loans and asset-backed securities. We are the number one Australian bank for global renewable transactions, and renewables now make up 75 per cent of our financed energy exposures.

As part of NAB’s climate ambitions and global signatory commitments, we are working with 100 of our largest greenhouse gas-emitting customers to support them in developing or improving their low-carbon transition plans. This may include investments in sustainable energy sources, more efficient processes and modern technologies.

While the task at hand for these customers is significant, we are pleased to see significant progress and transition maturity. The work cannot be left to heavy industry alone. As an interconnected and dynamic modern economy, taking a systems-based approach – as we have in our research – is vital for understanding the sustainable change required. Shifts in one area mean knock-on effects in others.

The NAB study has identified four systems that are critical to the transition: energy, raw materials manufacturing, mobility, and food and land use. In combination, these account for about 90 per cent of Australia’s carbon emissions, while the systems and their enabling services make up A$400 billion of the A$420 billion in new investment needed by 2050 to realise the national net zero ambition.

SUPPORTING INNOVATION

In corporate and institutional banking, we are working with customers across these key areas, including resources, heavy manufacturing, transport and the evolving energy supply chain.

As Australia’s leading agricultural business bank, NAB is also heavily involved in developing sustainable innovation for Australia’s primary producers, who make up such an important part of the national story and are at the forefront of climate change.

Our transition strategy means we are helping to decarbonise existing business operations through incentivising ambitious sustainability targets, with ever greater measurement and transparency for customers now and into the future.

With research and efficiency breakthroughs playing such a key part in Australia’s net zero future, NAB is supporting customers to further develop sustainable energy technologies. Key projects include backing investment in green hydrogen as well as new energy metals like cobalt and lithium, to enable the expansion of battery storage, electric vehicle transport and more.

While technology and innovation form the core of Australia’s decarbonisation roadmap, the nation is also uniquely placed to expand a credible carbon offset market – particularly for hard-to-abate sectors during this decade – also adding additional potential revenue streams for our farmers.

To this end, NAB is working on the demand and supply side of the compliance market for offsets while also deepening and scaling the voluntary carbon market through the secure and traceable Carbonplace settlement platform. Carbonplace is being developed together with a number of our international banking peers. It plans to use global integrity benchmarks to provide our customers with another valuable transition tool.

WORKING TOGETHER

By working closely with our customers and through our ongoing sustainability initiatives and industry partnerships, NAB is helping lead the way through this complex and far-reaching environment.

We recognise getting to net zero means everyone has an important role to play, with all pulling in the right direction in a coordinated approach. It is clear from the scale of the task that the investment decisions we make as a nation today must necessarily set up future generations for success as they eventually take up the baton for us in this critical endeavour.

Success will also mean extending transparency through better data capture and analytics, with more businesses reporting their direct and financed emissions in a simple and standardised approach across the whole economy.

The nation will need greater co-investment and collaboration from business, government and industry in low-emissions technology and in developing further solutions for hard-to-abate sectors. We must make the necessary, urgent adjustments today, while taking a long view in reviewing and learning as we go.

There is still much work to be done and it will not be business as usual. But in identifying and seizing these immense opportunities now, we will help build a strong and sustainable future for the nation today and for the generations that will join us to see it through.

Case study one: structural change from (below) ground level

A significant challenge to emissions reduction in Australia is the degree to which the national economy relies on natural resources. However, IGO demonstrates that companies in the resources sector can – with support from stakeholders including financiers – find opportunity in transition.

IGO began life in 2000, as a gold miner. It subsequently grew to become a diversified mid-cap, listed minerals company and, in 2017, announced a strategic update to a focus exclusively on “discovering, developing, and delivering products critical to clean energy”. IGO owns and operates nickel and copper operations, and also has a noncontrolling stake in lithium mining and processing operations.

The 2017 update was a major and ongoing change of direction. IGO has since divested gold facilities while investing heavily in its lithium joint venture, among other projects.

But the logic backing the decision was clear, according to Scott Steinkrug, Perth-based chief financial officer at IGO. “The shift of our purpose to a focus on providing the world with metals critical to clean energy was akin to a light bulb moment in 2017,” he tells KangaNews Sustainable Finance.

“As a management team, we realised we had a huge opportunity – and responsibility – to act in the interests of our planet to do what we can to respond to climate change, and seek to do this by producing metals involved in electric vehicle batteries, static battery storage and grid-scale electrification.”

Steinkrug describes global warming as “quite possibly the largest threat to civilisation we face today”. As a result, being able to shift direction from being a diversified miner focusing on base and precious metals to one that facilitates a cleaner planet “became an easy choice for our board and employees”.

The opportunity from lithium mining in particular should be clear. New battery storage technology is unleashing the full potential of renewable energy by allowing power produced from sun, wind and other sources to be stored and used when and where it is needed.

On a practical level, lithium also provides an opportunity to add economic value that is not available to operations focused on the extraction of many other raw materials. IGO has an approximate 25 per cent stake in the Greenbushes lithium mine and is also a 49 per cent owner of a downstream processing refinery in Kwinana, both in Western Australia (WA).

“The downstream refinery is arguably the more interesting part of the investment,” says Rob Hickman, head of client coverage, WA at NAB in Perth. “IGO will be refining spodumene [a mineral source of lithium] and producing battery grade lithium hydroxide in WA. This means an enormous amount of capex for the plant in Kwinana. Extraction is important and interesting, but the big win here is the value-add that is occurring onshore in Australia.”

“The shift of our purpose to a focus on providing the world with metals critical to clean energy was akin to a light bulb moment in 2017. As a management team, we realised we had a huge opportunity – and responsibility – to act in the interests of our planet to do what we can to respond to climate change.”

Button TextThis has positive environmental consequences, in the form of reduced transportation of raw and waste materials. It is also positive for the local economy, bringing long-term jobs to WA directly and through the supply chain. “It reduces the emissions intensity of the end product as well as helping create a new, specialist sector of the Australian economy,” according to NAB’s Sydney-based global head of sustainable finance, David Jenkins.

He continues: “IGO is just one example of opportunities that flow through the whole value chain into areas like manufacturing. We should be thinking about these things in Australia because we clearly have the natural resources that will be needed in future as well as the energy sources from the wind and sun. We are – or should be – incredibly well positioned.”

These types of positive outcomes are important in major corporate transition for reasons beyond the financial. IGO says it is keenly aware of the various aspects of its social licence including the impact of its strategic decisions on employees and communities.

The company acknowledged the “unavoidable impacts” of decisions like the divestment of its Jaguar and Stockman copper and zinc assets, and the transition to “care and maintenance” mode of its nickel operation, Long. “Significant planning went into these transitional activities and, while those affected will be the definitive judges, we believe our approach was best practice in… employee and community engagement,” IGO noted in its 2018 sustainability report.

Overall, IGO believes the shift in focus has paid off across its sphere of influence. “From our experience, the social benefits have been significant,” Steinkrug says. “This is most evident through our people, who have embraced our purpose and, based on recent survey results, continue to drive high levels of engagement of our people in our business. We attribute this to our people feeling they are making a difference when they are at work and that they are contributing to a cause beyond what mining companies have traditionally offered.”

The company also sees benefits in attracting new talent to its business. Because of its clear purpose and unique culture, Steinkrug continues, people want to work for IGO – evidence being the response rate the company gets when advertising for new roles.

INPUTS AND USAGE

The other challenge for a minerals mining and processing company is that, while its end product may make a positive contribution to the low-carbon transition, the processes involved can be emissions intensive. IGO has therefore introduced a range of measures designed to reduce the carbon footprint of its operations.

The company has endorsed the COP26 plans to accelerate action toward limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. “The part IGO can play in this call to action is to accelerate our own decarbonisation plans,” Steinkrug comments. “We aspire to be leaders in the acceleration to carbon neutrality and to be carbon neutral across our direct operations and activities by 2035, if not sooner.”

The company is developing a decarbonisation strategy addressing its supply chain and scope-three emissions and has a number of projects in place to contribute to decarbonisation. In 2020, it commissioned a 5.5MW solar farm – which it is now in the process of expanding to add a further 10MW of power generation. This allows IGO to reduce reliance on conventional power sources even further.

The company has established an internal carbon fund that allows projects’ viability to be assessed on environmental, social and governance metrics as well as financial ones. Steinkrug says the fund may be used to assist in furthering projects with lower carbon footprints even when other, more cost-effective, options may be available.

IGO also has various carbon offset programmes in place, such as targeting “credible Australian carbon credit unit purchases” that can demonstrate carbon reduction or sequestration.

IGO measures its carbon footprint through scientific verification processes including National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting, and it is also exploring other certification and verification schemes. It has its scope-one and scope-two emissions independently audited, with the assurance certificate included in the company’s annual sustainability report.

“Our assessment of a borrower nowadays is not based purely on whether we think it has the financial capacity to repay us but on whether we want to be associated with that company as a business partner, based on how it is operating.”

Button TextThere is similar scrutiny on the usage of IGO’s production. Jenkins says NAB is supportive of infrastructure used to facilitate and accelerate the production, extraction and refining of new energy minerals with positive environmental benefits. But energy transition is not the only way to use these raw materials.

“The challenge is ensuring the end product is then being used to meet decarbonisation trends,” Jenkins explains. “In battery production at utility scale or the electrification of cars, there is quite a clear end benefit. Deployment in some of the disposable devices we use on a day-to-day basis is rather more subjective.”

For IGO’s part, sphere of influence comes down to its positioning as a purpose-led organisation – with that purpose being to safely, sustainably and ethically deliver the products its customers need to advance the global transition to decarbonisation. IGO’s sustainability report is an extensive document and Steinkrug says the company is keenly aware of the consequences of failing to align with such a clearly articulated purpose.

“We are aware of the negative sentiment some companies have experienced when their ambition fails to translate into action,” he says. “There are legal and reputational risks associated with getting this wrong. We take climate change seriously and we aim to make significant and real contributions toward reducing our carbon footprint.”

The same issues of actually delivering on stated values are important to NAB as a financier. Hickman says the bank scrutinises factors as diverse as mining companies’ engagement with local communities and traditional landowners, and their use of reagents and consequent environmental impact as part of their licence to operate.

“Our assessment of a borrower nowadays is not based purely on whether we think it has the financial capacity to repay us but on whether we want to be associated with that company as a business partner, based on how it is operating,” Hickman reveals. “This is not just defined by whether the company is following rules – it is the intent to ‘live well’ and contribute to the community.”

Case study two: the port as hub for transport, energy and transition

Port of Newcastle has made significant commitments to reducing emissions – but it is also the world’s largest thermal coal shipping facility and currently derives the majority of its income from the commodity. It is investing in improving its own environmental impact today and managing a more diverse freight base in the years to come.

One of the greatest challenges of diversifying to a low-carbon economy is the fate of entities that will not form part of the future in their current form. For financiers, the easiest option might be straightforward divestment. But doing so effectively strands an asset or leaves it to other players to resolve the issues – which include the social impact of transition – or ignore them.

Port of Newcastle (PON) – which is jointly owned by The Infrastructure Fund (TIF), a Macquarie Asset Management (MAM) investment vehicle, and China Merchants Port Holdings – is a case in point.

The port’s chief financial officer, Nick Livesey, tells KangaNews Sustainable Finance: “The economy of the Hunter region, Newcastle and PON is very much based on coal. We know this is going to dry up eventually, and while we can all have our own opinions on exactly when it will happen we know we need to future-proof our business and also the city and region around it. We are using the money generated from coal to work out where we will go next and how to diversify. We want to be sure, whether coal drops to unsustainable levels or just winds down slowly, that there is still a thriving business here.”

PON has already come through one major forced realignment – the closure of BHP’s Newcastle steelworks in the 1990s. This demonstrates that a major change to the port’s revenue stream can be survived, while also providing a salutary lesson in not missing the opportunity to prepare: Livesey says the 10-year notice period BHP provided ahead of the plant closure was still not enough to prevent the demise of the steel industry delivering a shock to the local economy.

“The view has been taken that the appropriate thing for PON is to be reinvesting the large majority of its cash flows into diversification. To make investment of this scale requires constructive thinking between the management team, the board and the shareholders. It also requires supportive debt financing and lenders.”

Button TextSEEKING DIVERSIFICATION

The path forward for PON has to involve supplementing, and in time replacing, revenue from coal. This is a significant task: Livesey confirms that around 55 per cent of PON’s revenue in the past financial year came from coal transport, rising to closer to 70 per cent when coal-related property leases are factored in. The port is focused on incremental growth across multiple freight types in the medium term and the potential for new energy sources, including hydrogen, as a long-term game changer.

“Our investment is to try to get more varied trade coming through the port,” Livesey says. “There is a lot of potential to bring vehicle transport to PON and we are seeking to break into the container trade. A lot of containers from the New England and North West of New South Wales [NSW] region, including from local farmland, are currently going to Botany, or even to Brisbane and Melbourne, for transport.”

The opportunity should be significant. For instance, Hugh FitzSimons, Sydney-based division director in MAM’s real assets business, points out that New Zealand uses seven container ports to service its population of just more than five million, while NSW has one to provide for eight million people.

For PON, this means an ongoing investment of around A$50 million a year to increase capacity and efficiency for types of trade it already facilitates but hopes to increase – including wheat and built products – as well as to lay the foundations needed to break into entirely new sectors.

In the longer term, PON wants to play a role in the development of new energy sources including exploring Australia’s role in hydrogen and the potential development of a hydrogen hub based at the port. It is a long-term goal and Livesey says PON is not yet projecting any revenue expectations for hydrogen shipping. But, if successful, the hydrogen hub would be “a huge step change” in the port’s goal of reducing the share of revenue generated by coal to less than 50 per cent of its total by 2030 and down further from there.

Hydrogen and other alternative freight are in some ways a more appealing financial prospect than coal, too. Livesey explains that PON’s coal revenue generation is not huge on a relative basis because it does not process the commodity or own the related infrastructure – all it provides is the land and shipping channels.

“If we build the infrastructure for things like ro-ro [roll-on, roll-off] and container ships, and common user berths – where it is our infrastructure, for instance our loader, that is being used – we can charge for it and thus change our revenue mix relatively significantly,” he continues.

“The economy of the Hunter region, Newcastle and PON is very much based on coal. We know this is going to dry up eventually, and while we can all have our own opinions on exactly when it will happen we know we need to future-proof our business and also the city and region around it.”

Button TextFUNDING CHANGE

For the port’s owners and lenders, the goal is to help manage the complex intersection of unavoidable and critical climate goals with their impact on a substantial investment, and its local community and stakeholders. A long-term view is vital – but is one investors are prepared to take.

FitzSimons says the capital owners behind the PON investment are very conscious of the need to support diversification rather than exiting. He reveals: “Australian superannuation funds, which comprise the majority of the investors within TIF, are very aware of the generational nature of a lot of the assets we work with. Seaports are certainly a generational asset; PON, for instance, has been operating in a European history context since 1799.”

A long-term view is vital. FitzSimons says the A$50 million of annual investment PON is making with the aim of diversifying future revenue roughly equates to the annual distributions it was paying as recently as four or five years ago. The owners have had to agree to forego annual income to support a longer-term plan.

“The view has been taken that the appropriate thing for PON is to be reinvesting the large majority of its cash flows into diversification,” FitzSimons confirms. “To make investment of this scale requires constructive thinking between the management team, the board and the shareholders. It also requires supportive debt financing and lenders.”

NAB is a core lender to PON – and it is also willing to support diversification. In 2021, the bank structured a A$515 million sustainability-linked loan for the port as part of a A$666 million refinancing, incorporating an emissions reduction goal – to keep scope-one and scope-two emissions “below the 2025 trajectory level”, in line with PON’s “well below 2 degrees” science-based target – as well as other social sustainability performance targets.

David Jenkins, global head of sustainable finance at NAB, adds: “We would not be a passive partner. There is engagement with the MAM teams and with the port on a very, very frequent basis as part of our ongoing lending relationship. We provide input and test the level of ambition in the various sustainability-linked lending targets – including the diversification goals.”

Ambition is ratcheting up. The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) has previously endorsed PON’s scope-one and scope-two emissions reduction targets but its policy has now evolved – in response to which, Jenkins says, PON is working to quantify a baseline and a trajectory that align with SBTi’s methodology for the port’s scope-three emissions reduction.

Livesey says the port is doing what it can to collaborate with its tenants on energy transition. For instance, it now uses 100 per cent renewably sourced energy and wants to supply more of this to its tenants through its embedded network. Shipping as an industry has a challenging emissions profile, but PON is also working directly with Port Authority of NSW to address the emissions of vessels using the facility.

“The only way ESG will be successfully addressed is if there is communication and collaboration,” Livesey adds. “We can only do so much about vessel emissions by ourselves. By working with Port Authority of NSW, and then starting to work with the shipping agents and shipping lines, it becomes a lot more powerful.”

“There is engagement with the MAM teams and with the port on a very, very frequent basis as part of our ongoing lending relationship. We provide input and test the level of ambition in the various sustainability-linked lending targets – including the diversification goals.”

Button TextCOMMUNITY IMPACT

Understanding impact is not just relevant to the port’s emissions profile but also to the transition it is seeking to execute. Coal is a crucial component of the regional economy and the social cost of the industry’s eventual decline has, at times, been used in some circles as a justification for Australia to drag its feet on transition to a low-carbon economy.

PON and its financiers say assuming universal opposition to planning for a post-coal future would be underestimating the local community. FitzSimons says: “Newcastle has reinvented itself before. The steel trade is a recent example but, going back even further, the timber trade was – alongside coal – the first big industry in the region. That industry came to an end and the region moved on.”

Healthcare and new energy innovation are growing components of the Newcastle economy, while the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation’s energy centre, which hosts its solar field and energy research hub, is also headquartered in the city.

Livesey tells KangaNews Sustainable Finance: “Everyone in Newcastle remembers the impact of the steel plant closure and everyone knows coal is going to dwindle at some point – whether they think it is over two years or 20 years. There is a common feeling that there needs to be support for the port to lead the way to diversify, because doing so has a trickle-down effect across the whole economy of the Hunter region. It might come as a surprise how much goodwill and how much support there is.”

Investment in transition is a vital part of making sure these ambitions can be fulfilled while minimising the social downside of a declining industry. “The efforts the port team is making, to diversify, and the application of capital to achieve them, are very consistent with the approach of taking active steps to help different assets and regions undergo their own diversification and net zero journeys,” FitzSimons adds.

Marshalling capital: opening and widening access to sustainable investment and sustainable markets

The scale of investment required to navigate Australia’s decarbonisation amounts to a reimagining of investment and capital markets. Having access to sustainable finance is, in this context, not just critical for borrowers but will have to be facilitated for all types of investor. Building sustainable finance market infrastructure is also vital.

The Deloitte-NAB report argues: “Australia’s transition will require new investment and a shift in where capital investment flows. It calls for a ‘great reallocation’ of capital investment that will become the business of this decade, facilitated in large part by Australia’s financial system.”

NAB is guiding initiatives designed to facilitate this great reallocation. Two of these are its partnership with BlackRock’s iShares division to make investing in exchange-traded funds (ETFs) more accessible in Australia – incorporating sustainability considerations as a central part of the offering – and the bank’s investment in Carbonplace, a new carbon credit transaction network.

The ETF partnership makes a suite of BlackRock iShares ETFs available on the nabtrade platform. These include globally diversified and sustainable multiasset portfolios built using iShares ESG building blocks, as well as a portfolio based on investment themes centring on technological breakthrough and climate change. This provides two ways for retail investors to access diversified sustainable investment strategies.

The multiasset portfolios incorporate sustainability screens that tilt their allocation toward the equity and debt of better ESG performers. The thematic investment ETF, meanwhile, is based on five “megatrends” BlackRock has identified, all of which relate to sustainability. These are climate change and resource scarcity, demographics and social change, emerging global wealth, technological breakthrough and rapid urbanisation.

Chantal Giles, head of wealth at BlackRock in Sydney, explains: “Sustainability and ESG mean different things to different people. The multiasset portfolios incorporate ESG considerations at every stage of the investment process, forming a diverse portfolio of companies and bonds, whereas the megatrend fund seeks investments that will benefit from the shift we are seeing in how we live and work. The transition to net zero and sustainability are key parts of this shift.”

The idea is to give investors a way of allocating their funds to trends that are positive for growth but that are otherwise hard for retail investors to access economically, with the diversification benefits ETFs offer. Giles says ETFs as an investment tool are “democratising individual access to diversified investment tools”, and notes that the megatrend fund available on nabtrade combines some of the underlying thematic trends BlackRock has identified to achieve a good spread of opportunities.

“Within the iShares Future Tech Innovators ETF, for instance, we have combined six themes, in equal weights, within the technology megatrend to facilitate a better diversified portfolio. We want to offer long-term investing rather than trading individual ideas. It is a really great first step for investors who want to move into thematic and megatrend investing but don’t know where to start,” Giles comments.

“We have combined six themes, in equal weights, within the technology megatrend to facilitate a better diversified portfolio. It is a really great first step for investors who want to move into thematic and megatrend investing but don’t know where to start.”

Button TextDEMAND DRIVER

BlackRock and NAB believe there is clear appetite for this type of investment among retail ETF buyers. Giles points out that sustainability has become an investment norm in markets like Europe, including in core exposures. Simultaneously, thematic and megatrend investing has taken off globally in the past two years.

Fund flows to megatrend ETFs have held up even in the challenging market environment of 2022, Giles says. Meanwhile, the sustainability and ESG sections of the BlackRock website have consistently been the most heavily trafficked. “This tells us people want to invest in line with their values and that they are using these exposures to invest for the longer term,” Giles tells KangaNews Sustainable Finance.

Adrian Hanley, Melbourne-based executive, investment platforms and private wealth at NAB, says: “Individuals are not just looking for sustainable returns on their portfolios – they want this to be achieved in a sustainable way. This is what I believe the conversation about the great reallocation of capital really means.”

The scale of the reallocation of investment funds is potentially immense, Hanley says. There are more than 600,000 high net worth investors in Australia, defined as having A$1 million or more of investable assets. In total, these households control an estimated A$2.5 trillion of assets – out of the national total of about A$15 trillion.

Around 1.5-1.7 million Australians invest via ETFs, compared with 6.6 million individuals who hold direct equity investments. Hanley reveals that the ETF component has grown by one-third in the past couple of years. “This is one of the fastest-growing segments of the market, and investors’ priorities are to use the right kind of ETF provider, like iShares by BlackRock, to get cost-effective access – and to do it in a sustainable way as well,” he tells KangaNews Sustainable Finance.

“Individuals are not just looking for sustainable returns on their portfolios – they want this to be achieved in a sustainable way. This is what I believe the conversation about the great reallocation of capital really means.”

Button TextMARKET INFRASTRUCTURE

NAB’s investment in the Carbonplace platform reflects a different aspect of capital reallocation, in this case the need for market infrastructure to support changing and growing flows. NAB is a joint owner and developer of Carbonplace, together with global banks BBVA, BNP Paribas, CIBC, Itaú Unibanco, NatWest Group, SMBC, Standard Chartered and UBS.

In May, Carbonplace announced the successful pilot transfer of carbon credits through its system. This transaction demonstrated the capability of Carbonplace’s settlement technology to “significantly increase the speed, efficiency and security required to support the growing demand for voluntary carbon credits and, in doing so, to more effectively drive private sector capital towards global climate solutions”.

Involvement in Carbonplace made sense for NAB based on the role it expects carbon markets to play in Australia’s transition to a low-emissions future, the nature of these markets and what the bank’s customers will need.

“Voluntary carbon markets require accessibility, trust and transparency to grow at scale so we can maximise climate impact,” says Charlotte Cadness, executive, customer digital at NAB in Melbourne. “We work closely with our customers to support them in their transition, which includes funding the investments needed as well as making it easier to buy and sell carbon credits.”

“We will be able to partner with exchanges, marketplaces and registries across the world – the growing ecosystem developing in the carbon trading sector. The idea is that a user can go into any connected market to purchase its credits and then settle through Carbonplace.”

Button TextCadness points to research by McKinsey that estimates demand for carbon credits will increase by a factor of 15 by 2030 and 50 by 2050. “On this basis, we know today’s voluntary carbon market is not equipped to keep pace with rapidly growing demand for carbon credits,” she continues. “It is bilateral and OTC, so it can be slow and opaque. It can also feel quite risky – for participants on either side of the market – and greater trust really needs to be built in.”

The development of a platform like Carbonplace addresses many of these problems, and Cadness says the founders hope it will help promote liquidity and transparency in a growing market. “We will be able to partner with exchanges, marketplaces and registries across the world – the growing ecosystem developing in the carbon trading sector,” Cadness comments. “The idea is that a user can go into any connected market to purchase its credits and then settle through Carbonplace.”

The platform should also help with ensuring consistent standards. Users need to sign up to a rulebook that will ensure all members adhere to a single set of prudential rules. All carbon credits transacted on Carbonplace must be verified according to internationally recognised standards.

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.