Australasian corporates take the lead on ESG

A growing segment of corporate Australasia is stepping up to the plate on sustainability, taking the lead among peers and in many cases government. The issues are complex, especially when it comes to transition management, but the wins are starting to stack up – including in the capital-markets arena.

Laurence Davison Managing Editor KANGANEWS

It would be fairly easy to be cynical about sustainability and corporate Australasia. Australia has one of the world’s most prominent mining sectors – it ranks fourth for global coal production behind only China, the US and India – while its federal politics seems to be at least decade or two behind the global consensus on climate change.

New Zealand’s reputation is greener and it is a leading developed-world nation when it comes to renewable-energy generation. But its agricultural sector, among others, makes it a surprisingly large carbon producer on a per-capita basis – ranking higher than the UK, for instance.

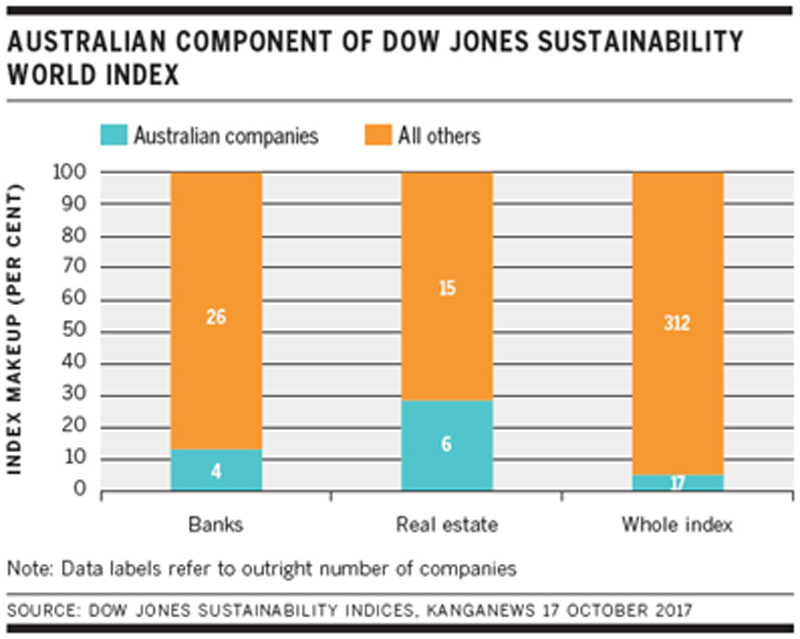

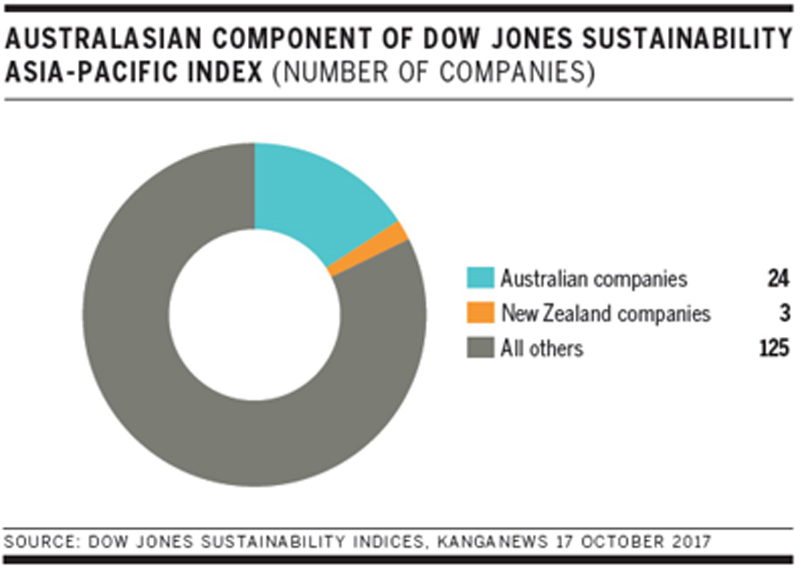

On the other hand, Australasian companies feature increasingly prominently in global sustainability rankings. Australian banks and real-estate firms were standouts in the 2017 iteration of the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index (see chart on right), while Australasia contributed nearly 20 per cent of the constituents of the 2017 Dow Jones Sustainability Asia-Pacific Index (see chart on right).

The momentum of sustainability within corporate Australasia appears to be growing as companies adopt, enhance and refine their own commitments and attempt to promote good sustainability practices in their supply chains and client bases.

This is not just a publicity effort. Sustainability, especially in the environmental realm, can have negative consequences and where necessary Australasian corporates have stood up to political and public opposition to the wider impact of their commitments.

Deploying genuine environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles at corporate level is complex, too. Commitments in this area create potential conflicts, internally and with stakeholders. Indeed, in some cases the individual components of ESG can even be in apparent conflict with each other. Some leading corporates are also trying to inculcate sustainability principles in their supply chains (see box below).

Perhaps the greatest degree of nuance comes in the context of environmental transition. Not all ESG-committed companies are inherently ‘green’ at face value. Two examples are AGL Energy – which, as of 2017, remains one of Australia’s most significant coal-fired energy generators – and Sydney Airport.

The point for companies like these is to acknowledge the required transition to a low-carbon future and understand how they should contribute to this process. Tomorrow’s world will still need air travel and reliable energy supply. The issue for major corporates in sectors like these is how they manage their own transition, support that of the wider economy and manage all their stakeholders’ needs in the process.

Finance and capital markets is one aspect of the holistic approach to sustainability. Australia’s equity market has woken up to ESG considerations and corporates say this component of their investor relations grows with every passing year.

The debt arena is coming up the curve rapidly, too – as demonstrated by innovative transactions and structures on both sides of the Tasman Sea. In Australia, Investa Property Group (Investa) brought the first-ever nonfinancial corporate green bonds to the market in March 2017. In New Zealand, Contact Energy (Contact) achieved a clutch of national and world records when it had a whole debt programme certified as green by the Climate Bonds Initiative in August 2017.

Take one and pass it on: encouraging good citizenship

For some Australian companies, sustainability principles go well beyond their own office space. The idea of encouraging peers and suppliers to get on board with environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards is catching on.

Sydney Airport is among those companies seeking to encourage good conduct in its sphere of influence. Its head of sustainability, Penny Barker, reveals: “We have a supplier code of conduct in place and we ask our suppliers to align with minimum expectations on ESG matters. These expectations align with the standards we set ourselves. We know our business partners have corporate-citizen commitments too and we look to partner with them to drive mutually beneficial outcomes.”

AGL Energy (AGL) has a similar code of conduct in place, covering factors as diverse as environmental standards, safety and employee policies on diversity, labour conditions and LGBTI considerations. “It makes sure we’re selective about who we do business with, because we want to ensure we’re aligned on these core values,” says AGL’s group treasurer, Bláthnaid Byrne.

The company applies a similar code of conduct in its funding chain, too. The motivation was no different – AGL’s banks are suppliers in the finance realm and the company wants to be aligned with lenders that share its core values.

Sustainability culture

While sustainability may be growing in prominence across the boardrooms of Australia and New Zealand, many leading companies say they have factored it into their strategic thinking for many years. Investa and Contact, for instance, say their capital-markets initiatives were the product of long-term alignment between corporate culture and ESG principles.

Louise Tong, Contact’s Wellington-based head of capital markets and tax, says: “Contact has been focused on sustainability – building out our renewable generation and reducing carbon emissions as well as sustainability more broadly – for years. I also became aware of a groundswell of interest in sustainable finance coming from the financial-markets community. It got to the point where it seemed apparent to me that these two trends were crossing over.”

Corporates also insist their sustainability goals are not siloed or sidelined but woven into the fabric of their businesses. Nina James, general manager, corporate sustainability at Investa in Sydney, tells KangaNews the company has a decade-plus track record of ESG leadership. It started with a fundamental business case for sustainability and moved quickly into capturing data to fine tune energy-efficiency savings in its property portfolio.

Investa’s sustainability team is small – two people, with two more in the environment and safety team, cover corporate sustainability strategy, asset-level environmental initiatives and safety across the platform. But James says this simply reflects the integral nature of ESG thinking across the company’s operations. “This business does sustainability every day, all day – it’s in the bloodstream,” she comments.

Sydney Airport also sees its sustainability goals as a natural component of its strategic direction as opposed to an external bolt on. Penny Barker, the airport’s head of sustainability, tells KangaNews its fundamental purpose is “to foster the growth of aviation for the benefit of Sydney, New South Wales [NSW] and Australia”. But this goal is consistent with an integrated ESG approach, she adds – and in fact the two complement each other.

“To deliver on our vision for the long term, we recognise that we need to balance social and environmental needs with our corporate objectives. To do this we know sustainability must be at the heart of everything we do,” Barker comments.

In practice, this means a commitment to safety and security as a top priority, as well as playing a part in climate-change mitigation, investing in the communities in which the airport operates and maintaining its position as an “employer of choice”.

AGL’s commitment to sustainability became a major media and political talking point in Australia in 2017, as the company stuck by its carbon-transition principles in the face of intense pressure from the federal government and certain sections of the media to extend the life of the Liddell coal-fired power station in NSW beyond its scheduled closure date of 2022.

The company sees sustainability as a logical component of its overall direction. Richard Clifton-Smith, senior manager, sustainability strategy at AGL in Sydney, tells KangaNews: “We’re committed to helping shape a sustainable energy future for Australia. Our approach to sustainability is being aware of the responsibilities we have to all our stakeholders, and the impact our decisions and actions might have on them.”

One aspect of this work is forward looking – understanding changes in the community and environment and determining the appropriate corporate response. For instance, Clifton-Smith reveals, AGL has conducted scenario analysis on the consequences of a carbon-constrained future and has reported on the consequences of changing trends in social and economic inclusion.

Transition positioning

For a company like AGL, the absolutely critical consideration is the role it should take in a transition it believes to be necessary and inevitable. This provides a clear example of the potentially conflicting nature of specific ESG considerations. Clifton-Smith describes the “energy trilemma” – a phrase coined by Australia’s chief scientist, Alan Finkel – that has been behind much of the political brouhaha around energy policy in 2017.

The trilemma is that Australians require reliable and affordable energy while at the same time transitioning as rapidly as possible to a low-carbon economy with low-emissions energy generation at its heart. This matrix is at the centre of AGL’s social and environmental considerations.

“It’s a societal issue that we can all see being played out in the newspapers and in political debates. We’ve been very transparent on this and we don’t shy away from the fact that it is a challenge,” Clifton-Smith tells KangaNews. “The point is that we can’t address one aspect in isolation – we have to consider these issues holistically. We have 3.6 million customers, so energy affordability is important. But energy affordability is linked to energy supply, so we’re working with our stakeholders towards bringing a new, reliable and lower-carbon generation mix into the system.”

As the owner and operator of thermal power stations with large and longstanding social footprints, Clifton-Smith says AGL recognises it is important both to the communities in which it operates and to its shareholders that the company identifies, consults on and appropriately times its options for rehabilitation of these sites. Cost is just one aspect, though increasingly boards are recognising that ESG goals and economic performance are not mutually exclusive (see box below).

Board buy-in and corporate performance

Australasian companies with strong sustainability commitments universally report solid board backing for their initiatives. Sustainability’s increasing ability to go hand-in-hand with positive economic outcomes is only helping.

“You can have all the great ideas you want, but nothing will happen if you don’t have supportive senior management and corporate culture,” says Bláthnaid Byrne, group treasurer at AGL Energy (AGL). “By the same token, existing culture benefits from and needs champions to push ideas.”

Byrne compares the way individuals within large organisations represent sustainability to innovation in corporate culture, in the sense that innovative people need a supportive culture to thrive while, on the flip side, companies benefit from fostering innovative individuals within their ranks.

Contact Energy (Contact) provides an illustration of how this can work in practice. Louise Tong, the company’s head of capital markets and tax, was prepared to champion the development of a certified green borrowing programme but required institutional support to make it a reality.

“We approach sustainability very much from the perspective of transition,” adds Bláthnaid Byrne, AGL’s Sydney-based group treasurer. “It’s not possible to turn off coal overnight. What we can do is lead the transition – particularly if we find the policy-setting backdrop isn’t as strong.”

In Byrne’s view, sustainability commitment is if anything even more critical for companies operating in less inherently ‘green’ sectors. She explains: “If you’re looking at what creates the greatest impact – using the environment as an example, but it could easily be community or any other ESG consideration – it’s great for, say, a hydro-power company to make these commitments but it doesn’t have much influence because they’re already there. The companies that can actually have the biggest influence and impact are those that are really pushing the transition.”

Investa’s view on commercial-property ownership, renovation and development paints a similar picture. Here, the transition aspect is largely encapsulated in the acquisition of poorly rated building stock and renovation to higher standards. In most cases, improving an existing building produces a better – if lower-profile – outcome than demolishing it and constructing a new one, however many National Australian Built Environment Rating System (NABERS) stars the new build might receive.

“The most sustainable building is an existing building that you can improve – certainly compared with having all the materials from a demolished building going to landfill,” explains Peter Menegazzo, executive director and chief investment officer at Investa in Sydney. “Of course a lot of this material will be recycled, but even so it leaves a far greater footprint than investing time, effort and dollars to enhance the status of an existing building.”

How this works in practice is that Investa does not rule out the acquisition even of zero- and one-star NABERS properties. What it will not do is take ownership of such a building and leave it at the existing level.

“We expect all our assets will get to a baseline level of 4.5-star NABERS, and we need to have a pathway for how this can be achieved,” Menegazzo adds. “It’s absolutely something that gets assessed during due diligence, and it’s not just about how a property rates now. It’s about what we do to get it to a better rating, how quickly this will happen and how much it will cost.”

Debt specifics

The emergence of the green bond has given Australasian corporates a way of flagging their ESG commitments to debt investors. To date, issuers say the charge on sustainability engagement from investors has come from the equity side – though debt-investor interest is picking up.

Menegazzo describes “a growing snowball” in the equity-investment realm, with ever-more investors pushing for information and reporting. He points to the Global ESG Benchmark for Real Assets (GRESB) as a key yardstick, with more than 800 real-estate funds globally now assessed under GRESB criteria. “Equity investors are saying, ‘this is the benchmark, you need to be part of it’. At survey time we get inundated with emails wanting to make sure we’re participating,” Menegazzo reveals.

Given this backdrop, as Australia’s only domestic true-corporate issuer of green bonds to date Menegazzo says Investa found it relatively easy to meet the product’s standards once it was confident about demand.

“Where’s the downside?” he asks. “We looked at the reporting standards and what we needed to achieve to issue green bonds, and to be honest they were all things we’ve been doing for years. It was a really easy conversation. We want to continue to evolve as an organisation, and we saw this as a logical progression for us.”

A company does not need to have been a green-bond issuer to have noticed growing interest in ESG in the fixed-income space. “While debt investors ultimately remain focused on credit quality, tenor and price, interest in green bonds and sustainable investment has rapidly increased,” reveals Sydney Airport’s treasurer, Michael Momdjian. “Even in the absence of green-bond issuance, our sustainability goals and ambitions resonate well with our more traditional debt investors.”

Sydney Airport also sees its sustainability goals as a natural component of its strategic direction as opposed to an external bolt on. Penny Barker, the airport’s head of sustainability, tells KangaNews its fundamental purpose is “to foster the growth of aviation for the benefit of Sydney, New South Wales [NSW] and Australia”. But this goal is consistent with an integrated ESG approach, she adds – and in fact the two complement each other.

“To deliver on our vision for the long term, we recognise that we need to balance social and environmental needs with our corporate objectives. To do this we know sustainability must be at the heart of everything we do,” Barker comments.

In practice, this means a commitment to safety and security as a top priority, as well as playing a part in climate-change mitigation, investing in the communities in which the airport operates and maintaining its position as an “employer of choice”.

AGL’s commitment to sustainability became a major media and political talking point in Australia in 2017, as the company stuck by its carbon-transition principles in the face of intense pressure from the federal government and certain sections of the media to extend the life of the Liddell coal-fired power station in NSW beyond its scheduled closure date of 2022.

The company sees sustainability as a logical component of its overall direction. Richard Clifton-Smith, senior manager, sustainability strategy at AGL in Sydney, tells KangaNews: “We’re committed to helping shape a sustainable energy future for Australia. Our approach to sustainability is being aware of the responsibilities we have to all our stakeholders, and the impact our decisions and actions might have on them.”

One aspect of this work is forward looking – understanding changes in the community and environment and determining the appropriate corporate response. For instance, Clifton-Smith reveals, AGL has conducted scenario analysis on the consequences of a carbon-constrained future and has reported on the consequences of changing trends in social and economic inclusion.

Byrne adds: “We’re very cognisant of the changing environment from an investor perspective, debt or equity, and we want to engage as much as we possibly can and be transparent with these investors – whether it’s through our sustainability reporting or via access to senior management. We recognise that the world is changing from a funding perspective as well, and we need to be mindful of this.”

The green-bond option could be open to Sydney Airport, and Momdjian argues that the claim it is difficult, or perhaps even impossible, for airports to satisfy green-bond criteria is a misnomer. He says the diverse nature of airport operations provides significant opportunities to invest in projects that meet green-bond criteria.

For example, Mexico City Airport issued US$6 billion of green bonds to finance in part the design, construction and development of a carbon-neutral and 100 per cent renewable-energy New International Airport of Mexico City. The bonds also received a top E1 score from S&P Global Ratings using its new green-evaluation tool.

“We have commenced processes to rate and measure the sustainability of our assets through the use of green-star ratings and we have already invested in a number of green-eligible projects including electric buses, solar panels and low-carbon buildings,” Momdjian tells KangaNews.

He adds: “We have started exploring the issuance of green bonds, particularly given their ability to encourage further sustainable investment, demonstrate our commitment to sustainability both internally and externally, and deliver positive capital management outcomes such as investor diversification.”

Byrne acknowledges that an AGL green bond would “potentially still face a lot of cynicism” at this point. But the company is watching the market carefully. “It couldn’t just be a case of ticking off the criteria – I would not be comfortable doing this. It has to be an authentic use of funds we can stand behind,” she concludes.

Pricing view

Contact and Investa both challenge the conventional wisdom that green bonds do not deliver a pricing benefit to issuers. However, both stop short of definitively claiming a pricing advantage in primary prints.

Tong says the idea that green bonds would not give an improved pricing outcome used to be something she was “quite cynical” about. She explains: “Going back a year or more, whenever anyone talked to us about green issuance I tended to feel that if investors were really trying to drive change through this asset class they should be willing to pay a premium to make funding of low-carbon assets more attractive.”

Things may have changed. “More recently, we have started to see differential pricing emerging in the secondary market,” Tong adds. “I think we will see widening in the primary space between the opposite ends of the market – between certified green bonds and, say, a coal or tobacco company. In fact, I suspect this will happen quite rapidly, and certainly quicker than I would have thought possible a year or two ago. There is certainly a groundswell of focus on this issue from investors.”

It is of course impossible to compare the pricing of a bond transaction an issuer completed with what it would have achieved in a different deal it chose not to pursue. But Menegazzo says a straightforward supply-demand perspective on Investa’s green-bond deals suggests the company benefited from the format.

“I actually question the idea that green bonds don’t offer a pricing benefit,” he says. “Our experience, once we got in contact with investors around bringing a product to market, was of a very strong response sufficient to give momentum going into both transactions. I firmly believe we got some pricing benefit, particularly at the back-end through knowing we had good support going into the deals.”

At the very least, Menegazzo agrees that engaging with funds seeking sustainable assets should give issuers a degree of additional confidence around execution risk that could be significantly more useful should funding-market conditions become less conducive in future.

“Doing green-bond deals certainly opened our eyes to one thing in particular – that the capital wanting to look at green debt-finance products is growing quite substantially. It just doesn’t have the products to invest into,” he reveals.

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.