After shocks

The most significant factor in global markets for close to a decade and a half has been abundant liquidity. Initially – and ironically – sparked by the liquidity-driven global financial crisis, central banks have flooded markets with funds and in doing so created unprecedented conditions and a raft of anomalous outcomes. But signs are now growing that at least some degree of reversion is underway.

Laurence Davison Head of Content KANGANEWS

The financial crisis and the pandemic spurred a massive fiscal and monetary response. In many parts of the world – Australia and New Zealand in this case being notable exceptions – monetary policy ran out of road within weeks or months of the collapse of Lehman Brothers and was swiftly supplemented by waves of QE.

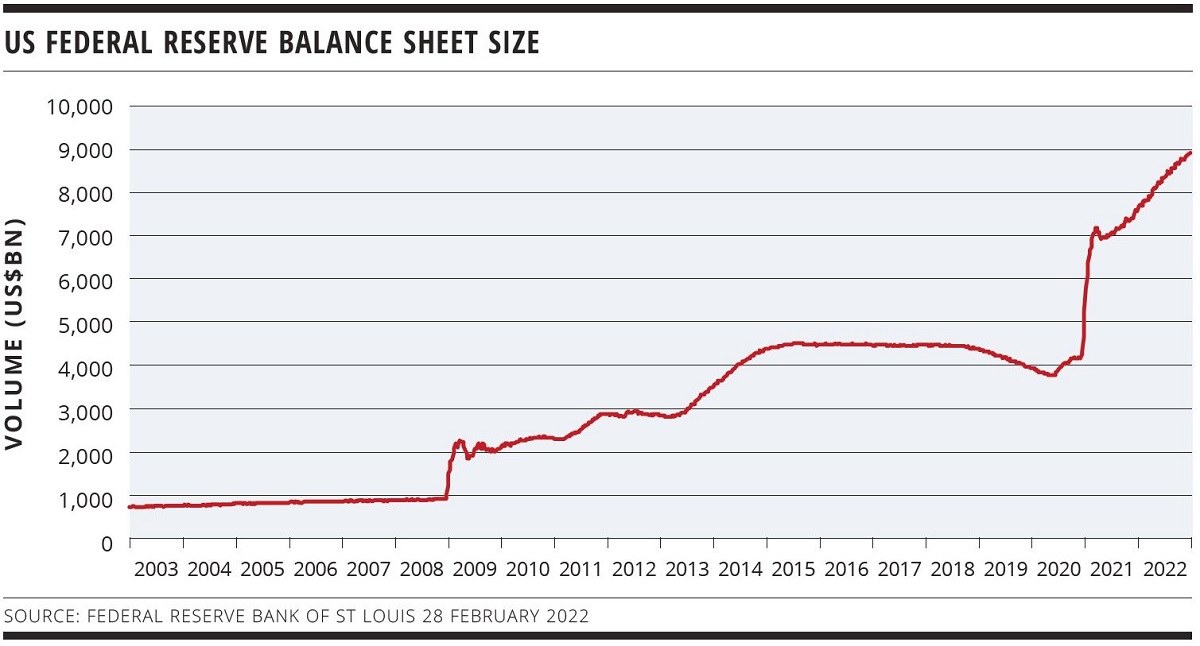

Far from being an emergency response that was quickly unwound, the spigots have been on in developed economies more or less ever since. The size of the US Federal Reserve balance sheet doubled in the space of a month in late 2008, but at the time this meant adding ‘just’ US$1 trillion (see chart). Even after the immediate impact of the financial crisis had settled down in capital markets, the Fed continued the supply of QE and its balance sheet swelled by a further US$2.5 trillion by late 2014.

COVID-19 hit just as the Fed was starting to make inroads in the ocean of assets it had accumulated. It pumped a further US$3 trillion into the economy in 2020’s immediate response, and a further US$2 trillion in a steady stream ever since.

To put this in perspective, in just more than 13 years the Fed’s balance sheet has grown by an amount – roughly US$8 trillion – that almost equals the combined GDP of the world’s third and fourth largest economies, Japan and Germany. As an annual growth rate, the Fed has been injecting more money into the US economy than the GDP of Sweden – which ranks 22nd largest in the world.

The European Central Bank (ECB)’s QE programme has been even larger and the Bank of Japan’s not far behind. In aggregate, think tank the Atlantic Council estimates global QE to be more than US$25 trillion equivalent since the financial crisis, effectively adding the world’s ninth-largest economy – Italy – to the world economy every year on average.

The impact of this extraordinary and ongoing injection of funds into the world economy is widely understood but no less remarkable for it. Bond yields and credit spreads went on a protracted bull run at the same time as the equity market kept setting new records. Property, especially residential housing, soared in value in most of the developed world. We were also introduced to a succession of seemingly ever-less-plausible new asset classes, from cryptocurrency and nonfungible tokens (NFTs) to special-purpose acquisition companies.

INFLATION BITES BACK

All of this went on without stirring the accompanying spectre of inflation. Fear of inflation was what slowed the ECB’s response in the early phases of the Eurozone sovereign crisis in 2020, causing much additional damage and for a time arguably threatening the very foundations of the Eurozone.

Up to the end of the first year of the pandemic, by contrast, inflation had been absent for so long despite the ongoing flood of liquidity into the system that many struggled to accept it was real when it started to emerge in 2021. Research published by Amundi in January this year points out that the average of analyst expectations for US inflation at the end of 2021 was 2 per cent at the start of the same year, while the actual outcome was 7 per cent.

Amundi’s group chief investment officer, Pascal Blanqué, argues that the psychological dimension has helped keep inflation expectations down. In effect, the fact most market participants and individuals have little or no memory of the last period of protracted inflation, in the 1970s – and have significant faith in policymakers’ ability to tamp down inflation as it emerges – caps their expectations at a relatively low level.

This has an impact on real-world inflation, given ongoing increases tend to depend on a feedback loop. In effect, if people believe increased cost of living is a temporary phenomenon their demands for higher wages will be less vehement, while businesses will be less inclined to pass on supply-chain cost increases they believe will ease.

In this context, the next few months could be critical. Blanqué warns that a shift in attitudes and outcomes can be “brutal at times and self-sustaining”. It is also not linear: if the psychology changes it could do so dramatically and quickly, leading to “an increased focus on the most recent data, especially if it continues to confirm strong divergences from previous patterns”.

“If tightening is the way forward, it seems inevitable that there will be some impact on asset values. These have been the great untouchable of the post-financial-crisis era: after the bloodletting of bank failures in 2008 asset markets from residential property to sovereign debt have seen largely one-way traffic.”

Central banks face a fearsome challenge, which is only heightened by the fact that the world continues to need liquidity. “Huge fiscal accommodation will be needed to finance the post-COVID-19 recovery, which has already driven debt to historical highs. Additional money creation, for example to finance the energy transition, will likely be required down the road, as humanity faces the great challenge of fighting climate change,” Blanqué writes.

The Reserve Bank of Australia is still to be convinced that inflation is persistent, or at least that the inflation Australia is experiencing is a more significant threat than putting the brakes on economic recovery via aggressive policy tightening. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand is at the other end of the central-bank spectrum, pursuing a “least regrets” policy that has seen it embark on a rapid monetary tightening path and begin to explore divestment of assets from its balance sheet.

Most global reserve banks are closer to the RBA’s position. Blanqué notes that the Fed has “done a great job” in its communication – which he says is a key driver of the psychological input to inflation expectations – but also believes it is stretching its dovishness to the fullest extent possible.

He argues: “We recognise that the Fed is behind the curve as never before and therefore any further price pressure or delay in the hiking cycle could be the trigger for questioning its credibility. So far, talk has been enough to fuel market trust, but markets will assess whether the Fed is really walking the talk as we move ahead.”

ASSET PRICES

It therefore seems at least plausible and perhaps even likely that the world is finally re-entering a phase of the cycle it had all but forgotten: monetary tightening and the unwinding of fiscal stimulus. Of course, this assumes no worse than a controllable deterioration in the geopolitical realm, which as of the time of writing was far from assured.

If tightening is the way forward, it seems inevitable there will be some impact on asset values. These have been the great untouchable of the post-financial-crisis era: after the bloodletting of bank failures in 2008 – which many investors were effectively protected against by the first wave of state balance-sheet support – asset markets from residential property to sovereign debt have seen largely one-way traffic. Corporate defaults have been minimal, asset-class correlation has all but evaporated and a growing cohort of individuals has been effectively locked out of the residential property market.

It is relatively easy to say, in effect, that something has to give. It is rather harder to guess where the fault lines will emerge. I suspect NFTs will be exposed as a de facto Ponzi scheme and there will be some form of reckoning in the less plausible corners of the equity market – perhaps we will hear less talk of stock market “unicorns”. But maybe this is just wishful thinking.

I am less convinced about a significant or protracted housing-market correction. Australia is not alone in seeing its governments’ economic policy apparently more or less entirely devoted to ensuring home owners – and, less explicably, housing investors – only ever lose value in the most marginal, managed and short-lived fashion.

It is hard to see this changing. Meanwhile, house prices sailed through a two-year period of sporadic but extended lockdowns and zero net migration not only undamaged but also on a strong upward trend. If Australians feel economically uncertain, they keep paying their mortgages even as policymakers rush to compensate for challenges as they emerge. If they feel economically confident, they fall over themselves to add leverage to acquire more property. Untapped demand is so strong it is hard to imagine a major correction in the absence of borrowing rates starting to head toward levels last seen in the 1980s.

One factor I will be paying close attention to is how, if at all, less abundant liquidity will play out in sustainable finance. Investor demand for enhanced sustainability credentials has less leverage when borrowers know they will be able to find capital regardless. If the buy side holds its line as liquidity starts to fall, it may find itself more capable of driving real behaviour change.

The questions are how long the reversion will take to bite, and whether that gives financial markets enough time to force through economic transition of the scale required.