Fitch highlights growing risks offsetting Australia’s sovereign strength

Australia’s sovereign rating will be tested in the coming months as the ramifications of the COVID-19 crisis play out through the economy, according to Fitch Ratings. A newly placed negative outlook on Australia’s AAA rating relates to significant downside risks in the domestic economy, including household debt, as well as global factors such as newly levied trade barriers.

In a 25 May webinar focusing on the macroeconomic and sovereign outlook, James McCormack, global head of sovereigns and supranationals at Fitch in Hong Kong, revealed that the rating agency does not expect global income to return to pre-crisis levels until at least 2022 or 2023. “We are not expecting a v-shaped recovery,” he adds.

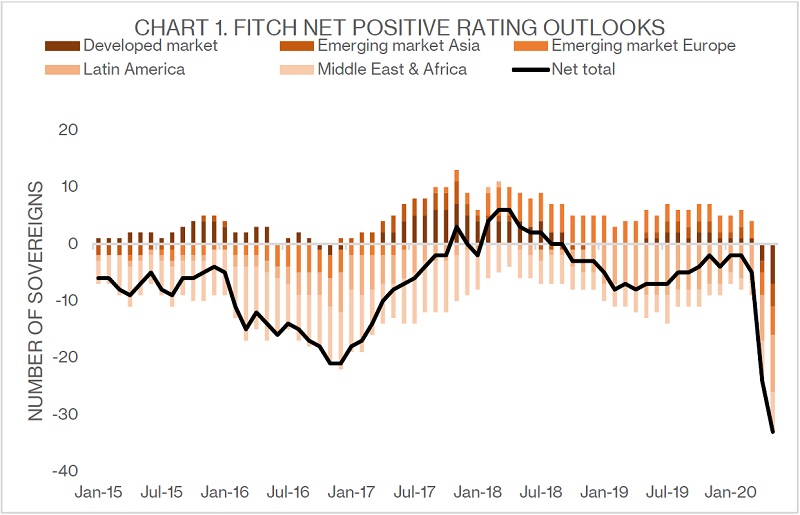

The COVID-19 crisis has sparked a record level of downgrades and negative outlooks on sovereign ratings (see chart 1). Fitch affirmed Australia’s sovereign rating but revised it to a negative outlook on 22 May, reflecting the significant impact COVID-19 is likely to have on the economy and public finances.

Jeremy Zook, Hong Kong-based director, Australian sovereign ratings at Fitch, says the deterioration in public finances will be material. This is despite the fact that, on the same day as the Fitch briefing, Australia’s federal Treasury revealed the cost of one of its key stimulus measures, the JobKeeper scheme, had been overestimated by A$60 billion (US$39.2 billion).

The Treasury’s revision led Fitch to reduce its 2021 forecast for gross government debt-GDP to around 55 per cent from 58.2 per cent. Nevertheless, the rating agency expects the deterioration in public finances will add to downward pressure on Australia’s sovereign rating.

Source: Fitch Ratings 25 May 2020

Global context

The COVID-19 crisis precipitated unprecedented fiscal stimulus from countries around the world as they grapple with the impact of an imposed economic hiatus.

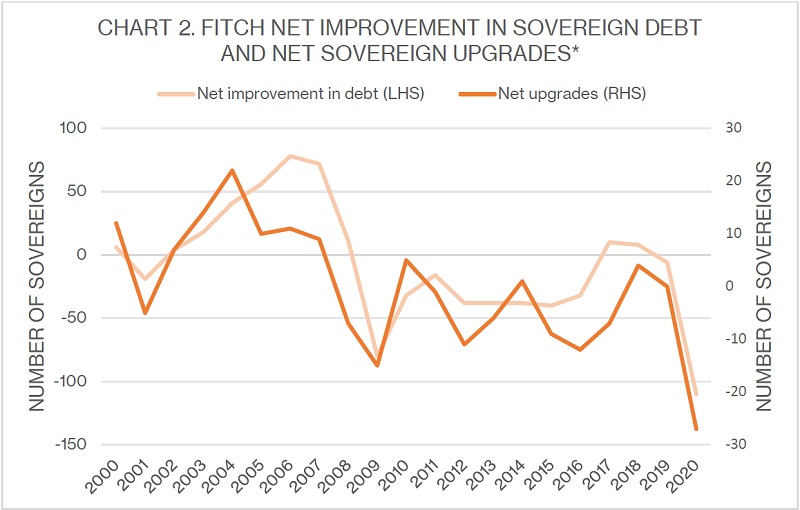

The factors which correlate with rating downgrades have all been moving in one direction. In particular, the number of Fitch-rated sovereigns that are improving their debt position relative to those with rising debt has fallen off a cliff (see chart 2).

With deteriorating debt positions essentially locked in, Fitch is making sovereign rating decisions based on expected fiscal consolidation after the crisis. “Our expectations on sovereigns’ ability to consolidate debt depends in large part on their track record since the financial crisis, as well as their respective starting points for deficits relative to rating peers,” says McCormack.

This approach is likely to stand Australia in good stead given its improved budget position in the years between 21st century crises. By contrast, McCormack adds that the track record of many global sovereigns has been poor in the last decade leading to poor starting points for the onset of COVID-19. Indeed, sovereign ratings were declining on average even before the crisis. This is particularly true for emerging market sovereigns, which now have an average rating below double-B for the first time.

*Net improvement in debt is number of sovereigns with falling debt minus number with rising debt.

Source: Fitch Ratings 25 May 2020

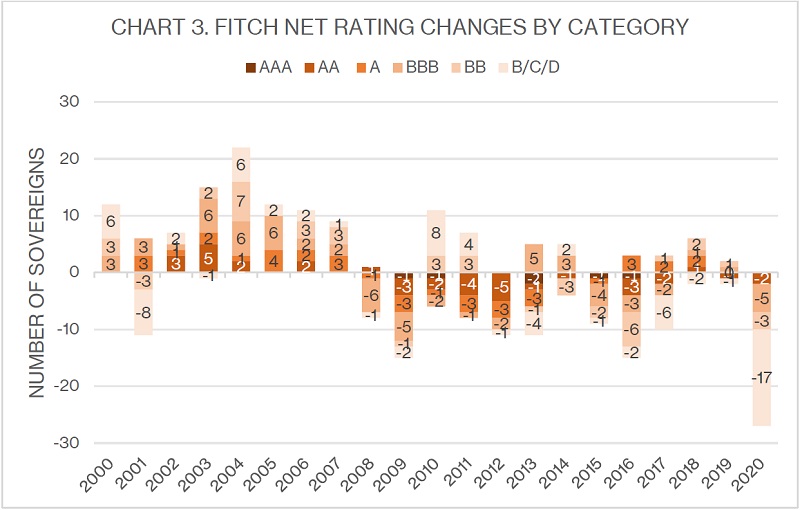

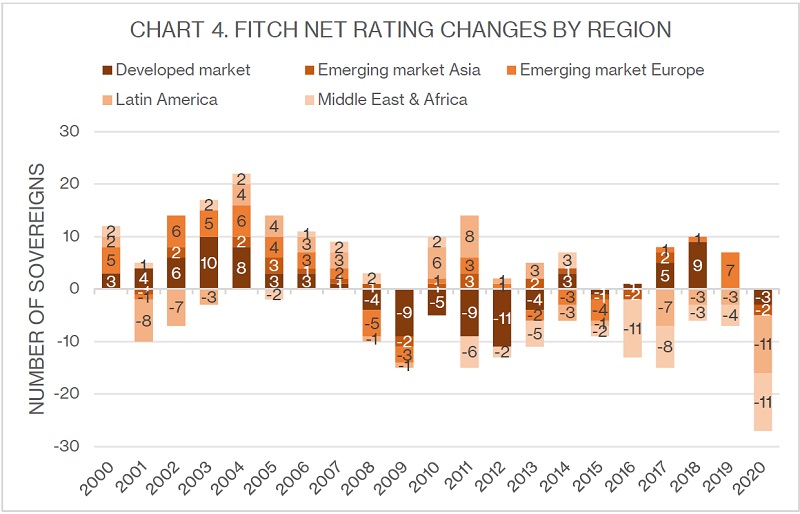

Fitch’s sovereign rating actions to date have primarily affected emerging market countries (see charts 3 & 4). As a result, McCormack says the aggregate value of downgraded debt in the COVID-19 crisis is, so far, low compared with other crises.

Source: Fitch Ratings 25 May 2020

Source: Fitch Ratings 25 May 2020

Australia’s position

The Australian government’s response to the crisis has been in line with other developed market countries, but several factors place its rating in a relatively favourable position.

Zook confirms Fitch’s view that the Australian federal government has a strong track record on fiscal consolidation and a good starting point with a budget close to being balanced before the COVID-19 crisis. “The Australian government has been very focused on surpluses and prudent fiscal management has in the past been key to electoral success,” Zook explains.

The rating agency still expects a significant widening in Australia’s fiscal deficit and a deterioration of public finances, however. Zook says a rising debt-GDP ratio has already eroded Australia’s position relative to the triple-A mean. Slippage in this ratio has been ongoing since Fitch upgraded Australia’s sovereign rating in 2011.

“Pressure will come onto Australia’s sovereign rating if we do not see sufficient plans to roll back the stimulus measures that have been implemented. A lot of the programmes are temporary so the rollback should happen naturally to an extent, but some of the stimulus measures will be difficult to take away,” Zook comments.

Meanwhile, Fitch expects Australia to be able to relatively easily attract the level of investment required to finance its record fiscal stimulus, given it has maintained interest rates above those of other triple-A sovereigns. McCormack adds that the purchase of government securities by the Reserve Bank of Australia, while supportive of demand dynamics, does not change sovereign credit fundamentals.

“Pressure will come onto Australia’s sovereign rating if we do not see sufficient plans to roll back the stimulus measures that have been implemented. A lot of the programmes are temporary so the rollback should happen naturally to an extent, but some of the stimulus measures will be difficult to take away.”

Downside risks

Australia’s health and economic position during the COVID-19 crisis is strong on a relative basis. Nonetheless, Fitch sees significant downside risks for the local macroeconomic outlook and, consequently, the sovereign rating.

In particular, Australia’s high level of household debt was manageable largely in the absence of a labour market shock. Such a shock has occurred and if unemployment remains elevated households’ ability to meet debt repayments could be reduced once fiscal support is rolled back. A substantial decline in house prices would have a similar impact with further negative consequences for the Australian economy and sovereign rating.

Fitch is also mindful of the Australian economy’s exposure to China. Stephen Schwartz, Hong Kong-based head of sovereign ratings Asia Pacific, expects a China’s economic growth to be 0.7 per cent in 2020. “This is shockingly low for what we have come to expect in China. But it is positive growth – which is in contrast to many emerging markets, where we are lowering growth expectations to negative,” Schwartz explains.

Chinese fiscal stimulus measures could prove a boon for some Australian exports, but others, such as beef and barley, have come into the political firing line. Zook says it is too early to tell what the effect of trade restrictions will be on Australian GDP, though they may be limited if Australian exporters can find alternative markets.

On the other hand, he adds that Australia’s economy could be particularly vulnerable if political tensions with China continue to escalate. For instance, if China restricts the flow of international students it would not only would have a large effect on Australia’s tertiary education sector but would also spill over into consumer spending and the rental-property market.

Declining immigration as a result of border closures represent a risk for all developed market economies, says McCormack. Fitch modelling suggests that, if immigration slows, most developed market economies begin to exhibit the low-growth characteristics and demographic challenges of Germany and Japan.

KangaNews is your source for the latest on the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on Australasian debt capital markets. For complete coverage, click here.

HIGH-GRADE ISSUERS YEARBOOK 2023

The ultimate guide to Australian and New Zealand government-sector borrowers.