New Zealand sustainable debt lines up a conversion

The New Zealand economy includes a clutch of sectors with significant potential to use sustainable finance to fund environmental transition. While some of the most prominent – including agriculture and transportation – will likely have to clear hurdles to align with capital markets, local sustainable-finance bankers are confident New Zealand is set for a step change in issuance.

Laurence Davison Head of Content and Editor KANGANEWS

Sustainable debt in 2021 means a lot more than ‘just’ labelled use-of-proceeds bonds. Nonetheless, green, social and sustainability (GSS) bonds have so far the most prominent means by which New Zealand borrowers align their sustainability and funding strategies, according to local intermediaries.

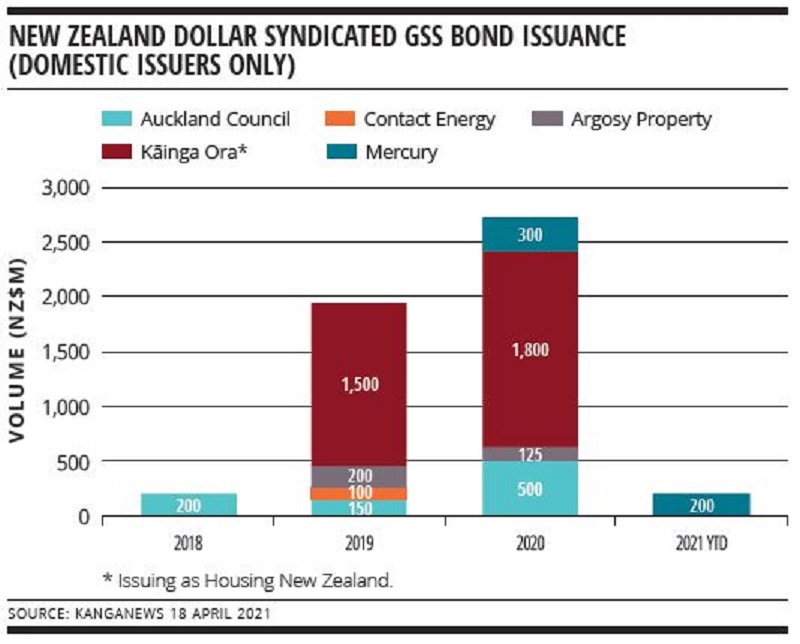

Takeup has been encouraging – especially borrowers’ willingness to return for repeat GSS issuance – if not overwhelming. Five local issuers have brought GSS transactions to the New Zealand dollar market since Auckland Council priced the first such deal, in 2018 (see chart). Westpac New Zealand has also issued in euros.

There have also been a smattering of labelled loans, mainly in sustainability-linked, rather than use-of-proceeds, format. Synlait Milk and Contact Energy are both repeat sustainability-linked loan (SLL) borrowers and four banks – ANZ, BNZ, MUFG and Westpac – have participated in these facilities.

New Zealand sustainable-finance bankers universally report that the pipeline for future issuance is positive, including engagement from a range of sectors and with many types of funding. This is not a vague hope for the future, either: there are specific expectations of an uptick in deal flow this year.

“It’s really busy, with a lot of interest from companies exploring how they can align their sustainability strategies with their financing plans,” says Dean Spicer, head of sustainable finance at ANZ in Wellington. “I think we will see a number of transactions over the course of the year – bonds and loans. I am pretty confident 2021 will be a record year for the market.”

To date, domestic GSS bond issuance has come exclusively from the government, property and energy sectors. But bankers say emerging interest is more broad-based. Joanna Silver, Auckland-based head of sustainable finance at Westpac, tells KangaNews: “We are in ongoing conversation with borrowers across a lot of sectors – a lot. We are working with a number of issuers at the moment and only a couple of them come from sectors that have previously issued sustainable bonds.”

“In New Zealand, when issuers are considering their approach to sustainable debt they are being driven less by investor demand and more by the needs of their other stakeholders. This means their employees, customers, the communities they operate in, and the young, talented staff they want to invite into their organisation.”

SUPPORTIVE CONDITIONS

Fertile ground for sustainable finance is largely the product of three factors: a supportive policy and regulatory background, the integration of borrowers’ own sustainability goals in the financing space, and investor demand. The focus is often on the latter, for understandable reasons: ultimately, public- and private-sector entities have to respond to their investors’ requirements.

In a world of ample access to liquidity, however, New Zealand’s sustainable-finance market is getting to grips with how it can evolve and grow without environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance being a precondition of accessing capital. In effect, investors often cannot afford to be too choosy about ESG as they are competing for a limited supply of appealing assets.

“When speaking to investors, the sense we have is that there is a lack of issuance diversity – let alone good quality deals that are also sustainable – in New Zealand,” Silver reveals. “If they see something with good credit and the price is right, they will invest – whether or not it’s green. Being green is a positive attribute in the transaction rather than a core driver for demand – though we anticipate that this will change as the market develops.”

This is not to say the New Zealand buy side is not interested in sustainable debt. Silver notes increasing interest from local investors in the global sustainability market and new structures. She suggests that four-fifths of investors have at least some interest in emerging innovative sustainability-linked structures and also highlights the emergence of new ‘dark green’ funds.

Even though some investors are heavily engaged with ESG and most are to some extent, the fundamental challenge is that an environment of easy liquidity inevitably removes one of the incentives for issuers to improve their sustainability performance. Simply put, there is enough money out there for companies to get funded with only a small, or even a nonexistent, penalty for being an ESG laggard.

At the same time, The New Zealand sustainable-debt market is evolving – it is just doing so primarily because of drivers from a wider range of stakeholders primarily on the issuer, rather than the investor, side.

Louise Tong, general manager, sustainable finance at BNZ in Wellington, explains: “Sustainable finance is not just about financial incentives. It aligns capital with sustainability strategy, brings business units together to drive greater understanding and engagement, and really changes the conversation internally. Typically, not much emphasis is placed on these soft benefits but they are very real in practice. This is why I think we will see growing momentum as more transactions get done.”

“It’s really busy, with a lot of interest from companies exploring how they can align their sustainability strategies with their financing plans. I think we will see a number of transactions over the course of the year – bonds and loans. I am pretty confident 2021 will be a record year for the market.”

Silver argues that it is necessary to redefine the concept of demand when it comes to sustainable funding. She comments: “In New Zealand, when issuers are considering their approach to sustainable debt they are being driven less by investor demand and more by the needs of their other stakeholders. This means their employees, customers, the communities they operate in, and the young, talented staff they want to invite into their organisation. Then there are regulators, lenders, policymakers and everyone who has a voice on their social licence to operate.”

Policy drivers are also in place. Spicer highlights two in particular as catalysts for corporate borrowers to enhance their engagement with sustainable finance. The first is confirmation that New Zealand will mandate Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) reporting, legislation to this effect being introduced on 13 April.

The hope and expectation is that the mechanics of TCFD reporting will provide companies with data that can also be used to support sustainable financing. Spicer explains: “There is a lot of focus within companies on their TCFD reporting, and this also raises the question of how they can use the reporting more widely – including in financing.”

The second is the Climate Change Commission (CCC) report, which was published in draft form on 31 January and is set to be finalised by the end of May. If adopted, CCC recommendations could reshape significant parts of the New Zealand economy in line with targets for power generation and electrification.

AGRICULTURE ISSUANCE

Interest in sustainable finance may be broad-based on the borrower side but some sectors are clearly in focus. The primary source of corporate issuance to date has been renewable-energy generation, and while New Zealand’s grid is already majority renewable there is still investment potential. However, new hydro power criteria developed by the Climate Bonds Initiative may have less impact than might be imagined (see box).

Elsewhere, two significant contributors to New Zealand’s emissions profile are commonly named as sustainable-finance opportunities by bankers. Both are confronting a substantial investment need over the coming years to manage transition to a low-carbon future.

“Agri and transport are the two big pieces of the pie when it comes to New Zealand’s national emissions profile,” Tong tells KangaNews. “They are both sectors at the heart of the just transition and, because of the scale of capital involved, sustainable finance could play a key supporting role.”

Hydro a case study in misalignment

Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) published long-awaited hydropower criteria in March this year. Hydro is a major component of New Zealand’s power generation mix. But rather than aligning positively, these two facts demonstrate the challenges even in best-practice, well-intentioned green labelling.

Hydro power provides more than half New Zealand’s total generation according to Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment data. A number of the main asset owners were active in the sustainable-debt market even before the CBI published its criteria.

New Zealand sustainable-finance bankers are quick to point out that there is no suggestion the criteria themselves are not valid or that local issuers’ assets are not legitimate renewable-energy providers. While local market participants agree that the CBI criteria represent best practice, unfortunately it seems they might be too late in development and applicability to have a material impact on the New Zealand market.

The proportion of New Zealand’s greenhouse-gas emissions – 53 per cent, according to a 2016 parliamentary report – coming from methane and nitrous oxide is by far the largest in the OECD. The majority of these emissions come from the agriculture sector.

Again, multiple factors will have to line up to support widespread investment in transition by agricultural producers. Several of these now appear to be in place: the policy environment, customer demand and the desire of producers themselves to have credible sustainability strategies.

On the former, the New Zealand Sustainable Finance Forum is working on its Sustainable Agriculture Finance Initiative. This, market participants say, will be a New Zealand equivalent of the agriculture component of the EU sustainable-finance taxonomy. It will establish standards and facilitate data gathering to the extent that Silver believes its adoption will pave the way for a substantial uptick in use-of-proceeds issuance from the sector.

As a key export sector, evolution in global markets also has a role in shaping New Zealand agriculture. The direction of international travel is apparent and it should pull New Zealand companies along with it. Tong highlights a Danone announcement from March last year that commits one of its subsidiaries – Horizon Organic, one of the world’s largest organic dairy producers – to becoming carbon positive by 2025, and Unilever’s commitment to carbon-label every one of its roughly 70,000 products.

While Tong also argues that the New Zealand agricultural sector deserves more credit than it typically gets for its commitment to and reporting on environmental transition, she also acknowledges that Horizon Organic’s starting point – the carbon intensity of its products – was significantly less progressed than the New Zealand dairy sector.

“The most important thing for the agri sector is that those that already have very good sustainability practices don’t rest on their laurels – because the world is moving very quickly. New Zealand agribusinesses need to keep evolving, including using all the tools available, so they remain at the forefront of sustainability globally,” Tong comments.

Spicer adds: “We have historically been a low-cost producer and I think the opportunity is for us to deliver sustainable product and to do so in a way that is highly efficient. I think there’s a niche for New Zealand to benefit from consumer trends.”

“The most important thing for the agri sector is that those that already have very good sustainability practices don’t rest on their laurels – because the world is moving very quickly. New Zealand agribusinesses need to keep evolving, including using all the tools available, so they continue to be at the forefront of sustainability globally.”

The main hurdles for the agricultural sector when it comes to sustainable-financing opportunities are twofold. One is that emissions-reduction options are still relatively limited. In other words, it is not that the sector is yet to invest in greenhouse-gas mitigation technology so much as the wherewithal until recently not being available in a cost-effective form.

The other challenge is more prosaic: the simple fact that capital markets are not the primary source of funding for the agriculture sector. Fonterra is a relatively frequent domestic bond issuer – printing more than NZ$4.5 billion (US$3.2 billion) since 2007, though nothing since 2018 and never in GSS format. Synlait’s NZ$180 million green loan, priced in 2019, is the sector’s only foray into labelled issuance.

“A lot of agri financing sits within the banking sector,” Spicer acknowledges. “The banks themselves are focused on sustainable lending so there clearly is an alignment of interests. I suspect the most natural option for agri companies themselves is a sustainability-linked instrument, because we are looking at a number of areas with negative-emissions pathways.”

TRANSPORT DIVERSITY

The other most commonly named sector with a natural need for sustainable-finance funding for low-carbon transition is transport.

There has already been some activity in the GSS bond space in this area: transport projects form a substantial portion of the eligible-asset pool behind Auckland Council’s NZ$850 million of green-bond issuance. Assets and projects include new and retrofitted railway rolling stock, the new city rail link and public cycleway assets.

Again, though, there are challenges involved in aligning low-carbon transportation with the sustainable-finance market. The most straightforward is that so much of the associated spending comes from central government, given there has not been any issuance and there are no current plans for New Zealand Debt Management to issue in GSS format.

“There is a public-sector funding requirement for transport infrastructure that is captured under the Crown’s overall funding,” Spicer explains. “There is an opportunity to do more direct funding, of the type we have seen recently from Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities, and this could be in GSS format. But the extent to which this approach will be used is unclear.”

In a way, this reflects the same issue as the lack of clear investor direction on ESG product: the relatively free availability of capital and shortage of investable assets. To date, the New Zealand government is the primary provider of transport infrastructure and simultaneously has been able to fund itself without requiring a GSS label. For as long as these conditions hold – and they seem unlikely to change – there will likely be no dramatic growth in labelled issuance from this sector.

There are emerging opportunities in the transport sector, though. New Zealand organisations are increasingly turning their attention to the potential for electrification of their light-vehicle fleets. There are some relatively simple ways sustainable finance can support this transition – for instance by green loans to fund electric-vehicle purchases or SLLs where one of the targets is fleet conversion. Sustainable finance may also have a role in more complex solutions, such as funding financial entities that provide electric-vehicle leasing to organisations or individuals.

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.