ESG in greater depth

In July, Commonwealth Bank of Australia and KangaNews conducted the second iteration of their annual environmental, social and governance survey of the Australian domestic fixed-income investor base. The survey was followed by an investor roundtable to discuss the findings and gain insight into the strategies behind the responses.

Helen Craig Head of Operations KANGANEWS

* All chart data compiled by KangaNews July 2021

The survey suggests Australia’s fixed-income investor base believes environmental, social and governance (ESG) integration is moving in the right direction, even if some of the year-on-year improvements are marginal. Investors participating in the roundtable are generally supportive of the extent and direction of the strides the market is taking – though they continue to identify areas where more work is needed.

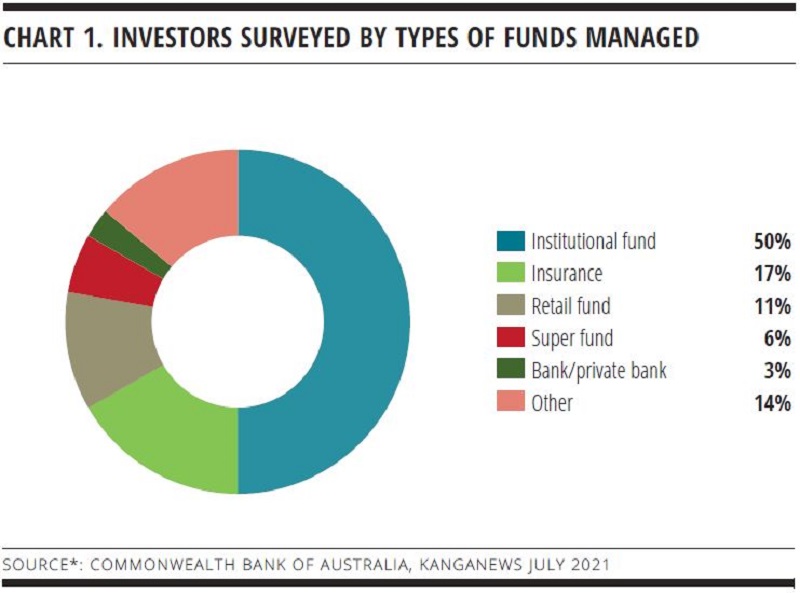

More than 35 Australian-based investment firms completed the survey. They include boutique funds, asset managers and owners, and private debt funds (see chart 1). The survey did not target specialist ESG investors but aims to blend the views of fund managers with specific mandates in the space with those of mainstream fixed-income managers.

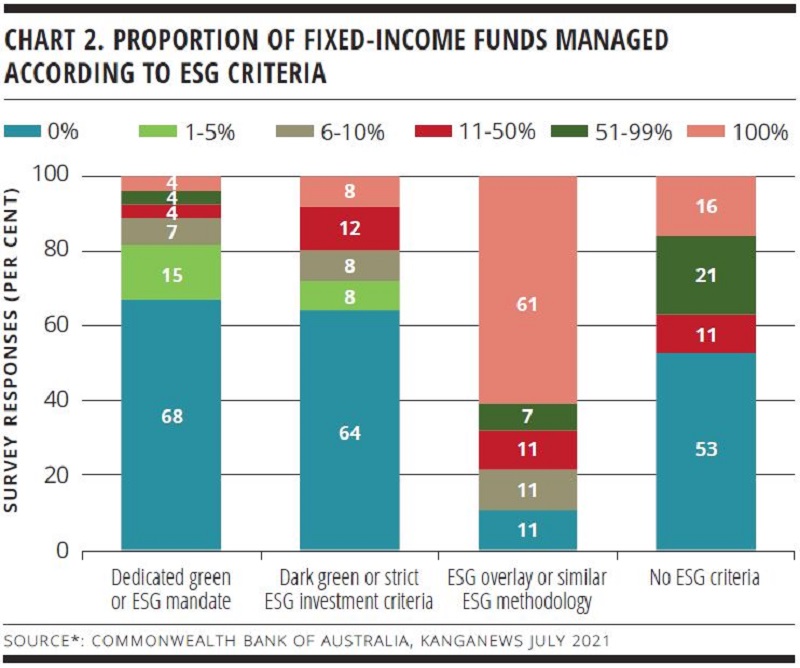

The scale of fixed-income assets managed under ESG mandates in Australia is growing according to the survey results. More than 80 per cent of respondents indicate their firms apply an ESG overlay to more than 10 per cent of their assets under management, and 61 per cent say they use this approach across all their funds (see chart 2).

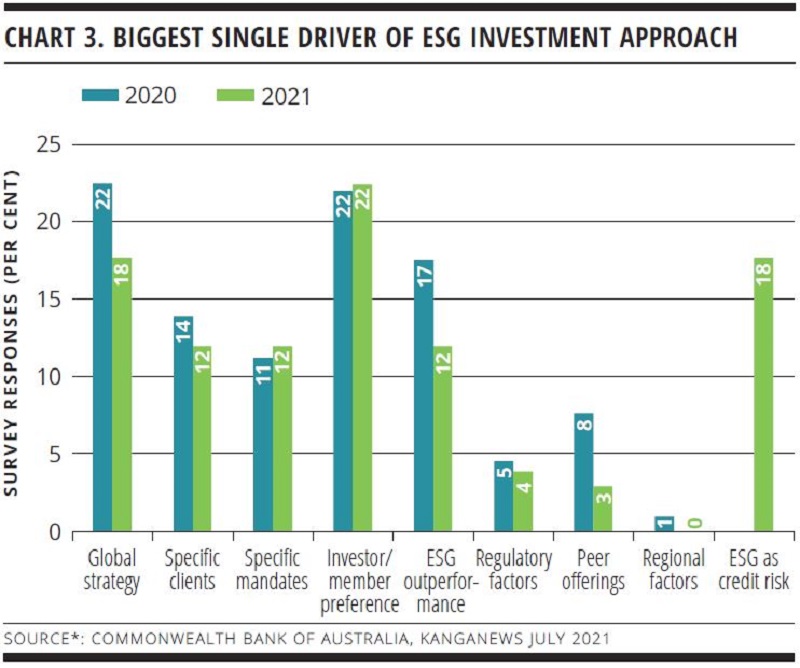

The 2021 survey demonstrates the extent to which the drivers of investment approach are changing. Head office and company strategy, labelled-issuance outperformance and peer strategies all declined as motivating forces for ESG uptake between 2020 and 2021. End-investor and member preferences, and – a new response option for 2021 – a greater understanding of the credit risk associated with ESG are the most significant drivers this year (see chart 3).

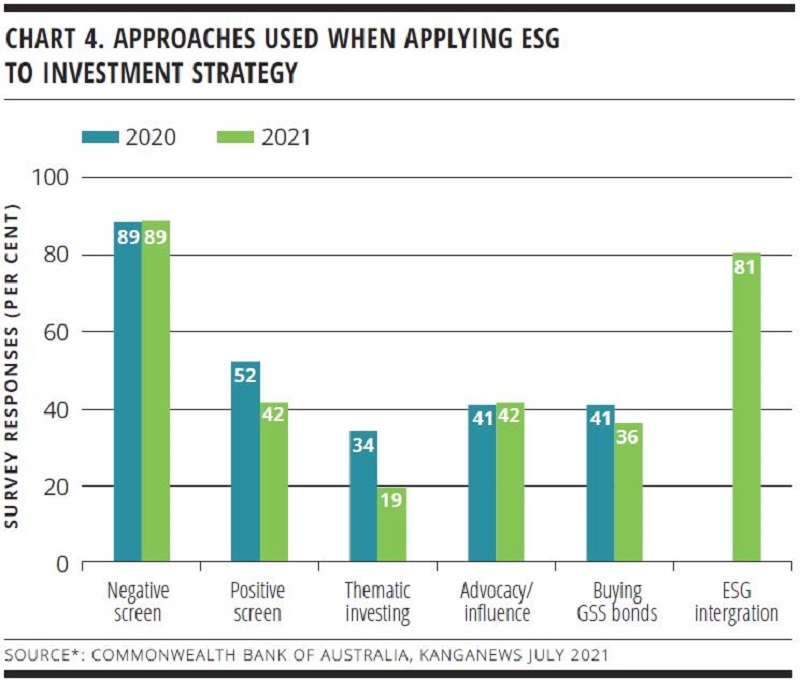

Negative screening remains the most-used single ESG approach across survey respondents, at 89 per cent in 2020 and 2021. There is widespread but not consensus usage of a range of other practices including positive ESG screening, thematic investing and buying labelled green, social and sustainability (GSS) bonds (see chart 4).

The 2021 survey added the option for investors to note that their ESG analysis is integrated into the existing credit process. Four-fifths of surveyed investors report they take this approach – almost as many as use negative screening.

Marayka Ward, senior credit and ESG manager at QIC in Brisbane, explained at the post-survey roundtable that the pattern of evolution is not surprising considering the number of end investors that have signed up to the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) in the last year and the increasing focus on corporate misdemeanour. Ward said commitment to PRI ought to cause investors to think more deeply about their processes.

“We have seen considerable uptick in questionnaires from consultants and clients – we have received 26 in 12 months, many of which were driven by modern-slavery reporting requirements,” she revealed. “Some took the opportunity to expand into other parts of the ESG universe, for example asking us to explain our overall ESG processes.”

The same techniques of ESG management – including negative screening – apply in the private debt space. Lucie Bielczykova, associate portfolio manager at Revolution Asset Management in Sydney, said at the roundtable: “As private investors, we are in for the life of a loan. A common characteristic of the assets Revolution screens out is that they carry significant refinancing risk. We don’t want to be left with stranded assets, so negative screening is a particularly important tool for us.”

While development is at the margin rather than revolutionary, the Australian investment market certainly appears to be progressively adding maturity and sophistication to its ESG approach. The fact that negative screening is the most commonly used single technique may suggest it is often the first step in a more detailed process.

Artesian Capital Management uses a three-stage process, explained the firm’s Sydney-based managing director, David Gallagher, at the post-event discussion. This starts with analysis using the SASB [Sustainability Accounting Standards Board] materiality map, including whether companies and sectors manage material risk, whether and how they report on greenhouse-gas and scope-one, scope-two and scope-three emissions, and how committed the company is to ESG including board buy-in.

“I think some investors used to believe they physically had to go into their pockets and cost-share up front – not really appreciating that if they are buying a labelled bond through an issuer’s vanilla curve, this is effectively how they were paying for it. As the market has evolved, I think investors are more comfortable that they can do good and still perform well.”

Button TextThe output of this detailed analysis is usually a comprehensive report, Gallagher continued. “For companies that make it through the negative screen, the next step is to carry out fundamental credit analysis including seeking out topical or ESG risks that are not priced in compared with other names within the same sector.”

The final stage applies to labelled bonds only. Here, Artesian carries out comprehensive use-of-proceeds (UOP) analysis at security-by-security level. Gallagher said it is entirely possible for a company to pass Artesian’s ESG and credit screening but then to be knocked out of investment consideration at the UOP stage.

Pendal embodies the ESG integration approach. George Bishay, portfolio manager at Pendal in Sydney, explained that the fund manager merges ESG analysis within its credit processes. It does so by examining material ESG risks associated with an entity or a sector to determine whether these risks are managed well enough.

“Ultimately, the concept of material risks being managed well enough or not is a decision in its own right and can be separated from other fundamental analysis decisions,” Bishay added.

“It is not the end of the story even when we identify material risks. Where we can, we will continue an engagement process with the issuer in the hope that it begins to manage these risks and we can eventually include it in our investible universe.”

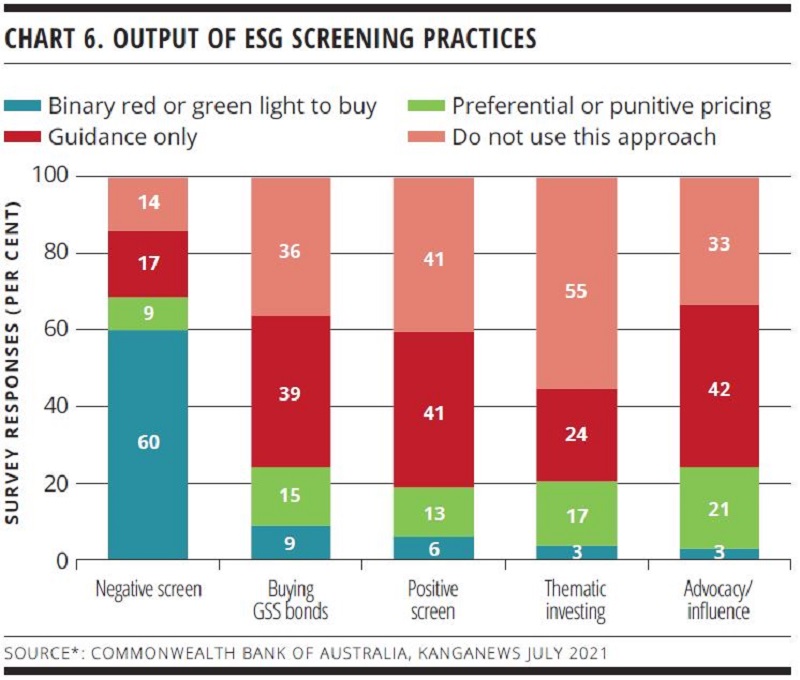

Button TextIn a further indication of the growing integration of ESG analysis in the Australian fixed-income market, the survey shows a marginal increase in the importance of ESG factors other than negative screening in the investment process. Close to 80 per cent of 2021 respondents say ESG has a significant or somewhat of a role in investment decisions, up by 6 per cent year-on-year (see chart 5). Other than negative screening, however, ESG analysis typically provides guidance to the investment process rather than a direct pricing signal or an outright red or green light (see chart 6).

INCREASING ENGAGEMENT

Investors at the roundtable described the outcome of this enhanced analysis process as in many cases requiring increased issuer engagement as an additive ESG approach.

For equity investors, the ability to use active ownership to advocate for good corporate governance and to improve the long-term value of a company has been a mainstream investment concept for some time. Despite not having shareholder voting rights, debt investors say they are increasingly using engagement techniques.

“A big change for us in the last 12 months is the engagement we have had with issuers,” Pauline Chrystal, portfolio manager at Kapstream Capital in Sydney, said. “Where an issuer is at now is not the highest priority but rather its progress made and its willingness to embrace change, increase disclosure and engage with investors to tackle risk.” Investors suggest corporate engagement is an alternative to screening out issuers whose activities might otherwise simply exclude them from portfolios.

Pendal’s dedicated strategies have a hard exclusionary screen and the fund manager will not invest in ESG laggards. Bishay added: “It is not the end of the story even when we identify material risks. Where we can, we will continue an engagement process with the issuer in the hope it begins to manage these risks and we can eventually include it in our investible universe.”

“In advance of the launch of the SLB it could be useful to talk to investors. Dealers could provide them with a range of potential targets the issuer would like to embed into the transaction, and investors could offer their views on which are going to be most relevant. This would avoid a situation where, for example, one KPI isn’t deemed as ambitious as the first.”

Button TextIt is not just investors making demands of issuers, and in fact the qualitative conversations debt investors are able to have can be richer than equity investors’ votes. Gallagher explained at the roundtable: “In many cases, companies’ ESG elements are still embryonic and they are interested to talk to us and to get our feedback. This is an alternative but powerful way to engage.”

The extent of power debt investors have also depends on the issuer’s reliance on debt as a funding tool, Bishay added. “This also includes the size of the investor base. If it is a large issuer whose paper is in demand from a wide investor base, individual investors will have less sway. The way we go about our engagement is to explain to the issuer that the size of our bond exposure is based on the outcome of our conversations. A positive outcome supports a larger exposure, and vice versa.”

Corporate engagement is key in the private market, Bielczykova said. “We are in a unique position in the private market because we have direct access to management as investors and originators, giving us a good basis for our risk assessments. We cannot discount the fact that we are still ‘just’ a debt holder. But this still allows us to have some influence on corporate social responsibility through things like higher margin hurdles if the company is carrying higher – but managed and mitigated – risk.”

DEVIL IN THE DETAIL

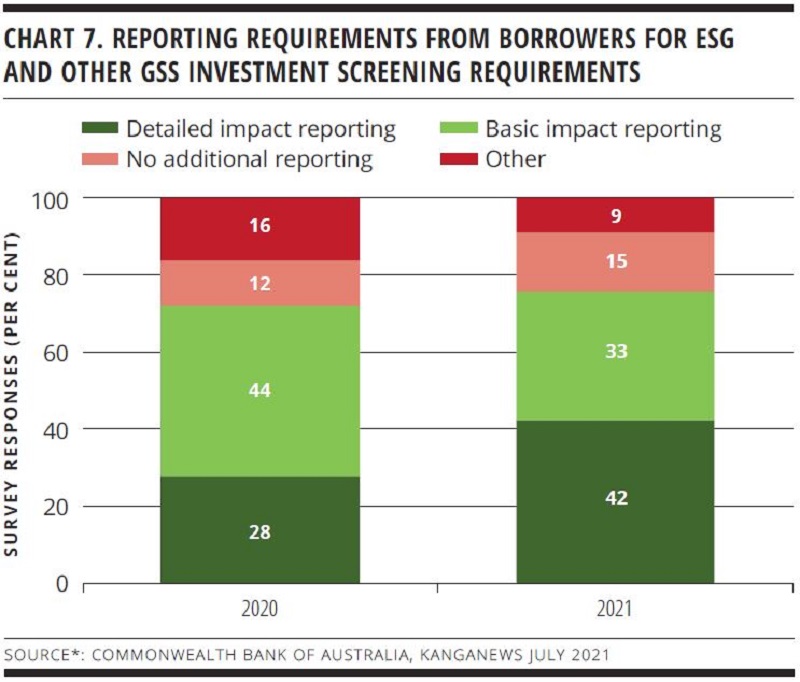

Anoticeable change in sentiment in the 2021 survey is investors’ expectations and requirements in relation to issuer reporting – specifically the level of detail fund managers want.

Whether at issuer level or transaction specific, a plurality of survey respondents want to see more detailed issuer reporting. This marks a change from the 2020 survey, when the largest single group of investors was satisfied with “basic impact reporting” (see chart 7).

Gallagher believes these demands are a reflection of the increasing sophistication and detail of the reporting investors themselves are providing. He explained: “We are constantly canvassing companies to improve their reporting, whether in line with TCFD [Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures], PCAF [Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials] or other requirements. We ask companies to improve their reporting so we can improve our own reporting back to our investors.”

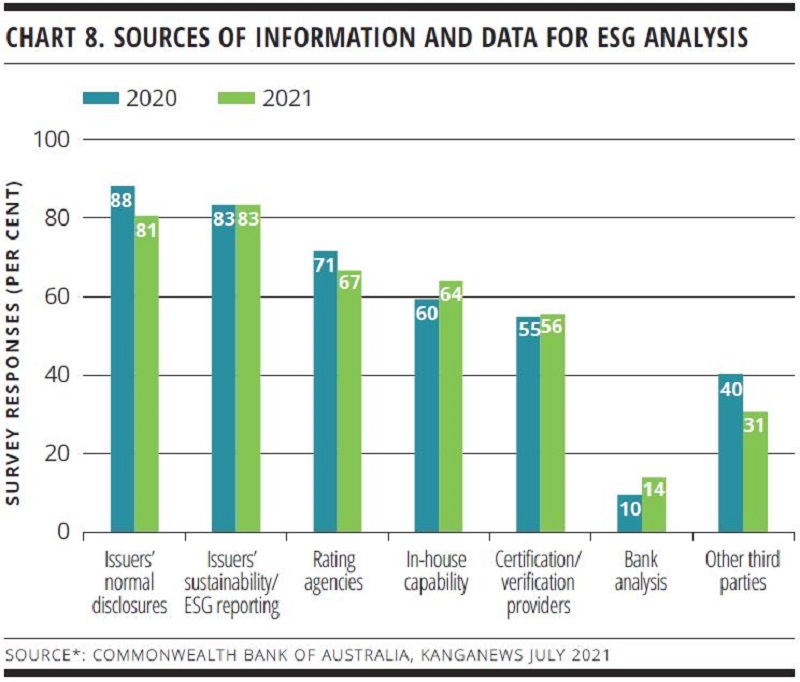

In a sustainable-finance market in which reporting and measurability are becoming increasingly important to a range of participants, investors are seeking information from a wide range of sources to support their ESG analysis. The picture here is largely unchanged from 2020: more than half the investors surveyed use all of issuers’ sustainability reporting and normal disclosures, their own in-house capabilities, rating agencies, and certification and verification providers to inform their ESG analysis (see chart 8).

Asset managers note the broad range of options available and suggest access to multiple sources of information is important. For example, Ardea Investment Management’s Sydney-based principal, Tamar Hamlyn, explained that ESG investment in the government fixed-income sector is a very different game from the credit space (see box).

“For companies that make it through the negative screen, the next step is to carry out fundamental credit analysis including seeking out topical or ESG risks that are not priced in compared with other names within the same sector.”

Button TextWhen it comes to sources of information, Hamlyn pointed out traditional rating-agency methodologies place relatively little weight on specific ESG risks, including climate risk, and quite high weight on mitigation and governance issues. This means ESG-poor sovereigns such as Australia can still score highly on a traditional credit-rating matrix.

“The rating agencies give large weight to the fact that Australia is a well-governed, western economy with a strong institutional base,” Hamlyn said. “This is notwithstanding the enormous risks we face on climate change and the fact major official investors globally are no longer buying our bonds.”

The challenge is in finding sources of information that enable investors satisfactorily to meet client and regulatory reporting requirements. “Enormously different metrics are used across the various areas we deal with and these can at times give us totally contradictory signals,” Hamlyn added.

Bielczykova revealed at the roundtable that information is limited for investors in private debt. “There is very little coverage by deal arrangers, brokers and even rating agencies even on credit-related issues, let alone ESG-specific factors. This means we rely on information provided by sponsors and management, as well as independent due-diligence reports carried out as part of transactions’ syndication process. We then use our own internal capabilities to assess the information.”

Even so, Bielczykova also said the quality of information is improving as companies increasingly add to what they make available and improve their reporting processes to become more transparent.

“The investor voice is clearly critical in the development of the SLB market. In a general sense the most important point is communication and the fact that there does not need to be a deal in or coming to the market for this communication to start. What we need is ongoing dialogue, particularly when it comes to new types of transaction structure.”

Button TextLOOKING FORWARD

One of the biggest issues on which the Commonwealth bank of Australia (CBA)-KangaNews survey seeks to shed light is whether investors or issuers should bear the brunt of the upfront cost of improving ESG outcomes. Relative to survey outcomes 12 months ago, investors appear to be giving up some ground.

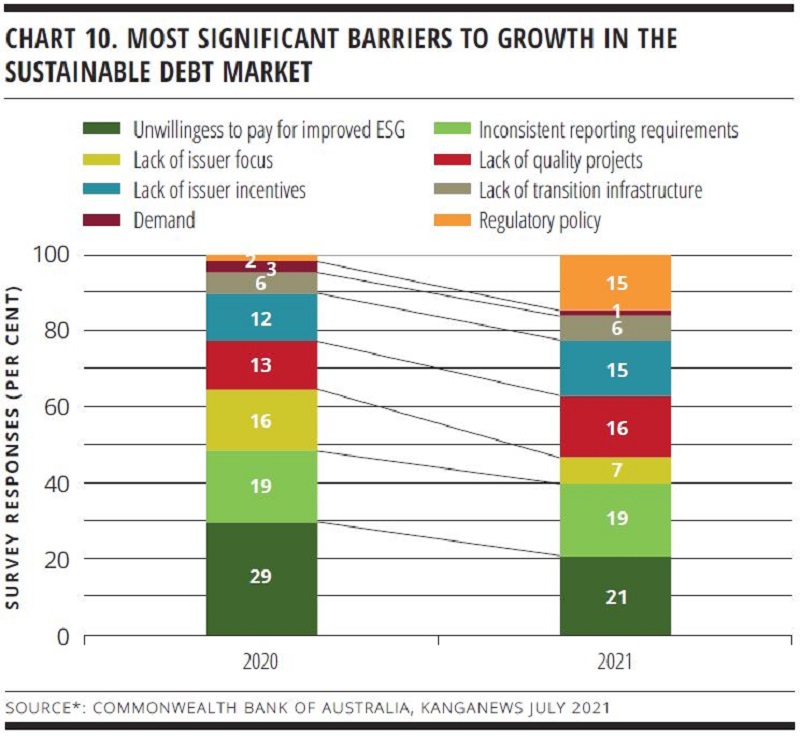

In the 2020 iteration of the survey, more than 60 per cent of respondents said they were not willing to offer any degree of preferential pricing for GSS bonds. A clear change in the investor view can be seen in the 2021 survey data, as only a third of respondents say they would not be prepared to pay any premium for a UOP GSS bond (see chart 9). At the same time, investors say desire for improved ESG outcomes but lack of willingness to pay for them is less of a barrier to growth in 2021 than it was in 2020 (see chart 10).

Ward argued at the roundtable discussion: “I think some investors used to believe they physically had to go into their pockets and cost-share up front – not really appreciating that if they are buying a labelled bond through an issuer’s vanilla curve, this is effectively how they were paying for it. Investors that were new to ESG investing thought a good way to get runs on the board was to buy some green bonds and build up a portfolio. As the market has evolved, I think investors are more comfortable that they can do good and still perform well.”

This evolution of investor mindset can be seen clearly through market dynamics – specifically the ongoing and significant supply-demand imbalance. Anthony Kritikides, executive director and head of institutional sales at CBA in Melbourne, added: “Recent GSS deals have been at least 2-3 times oversubscribed and the situation is not helped by the fact investors have tended to buy and hold – so it is proving difficult to find stock in the secondary market.”

“We are in for the life of a loan and a common characteristic of the assets Revolution screens out is that they carry significant refinancing risk. We don’t want to be left with stranded assets, so negative screening is a particularly important tool for us.”

Button TextAccording to some, the market may have moved on entirely from a pricing debate on GSS bonds. Bláthnaid Byrne, director, sustainable finance at CBA in Sydney, said at the post-survey roundtable discussion: “The impact on pricing in GSS issuance is largely minimal. It is more of a communication tool. The value is in the demonstration of an issuer’s commitments to its ESG strategy.”

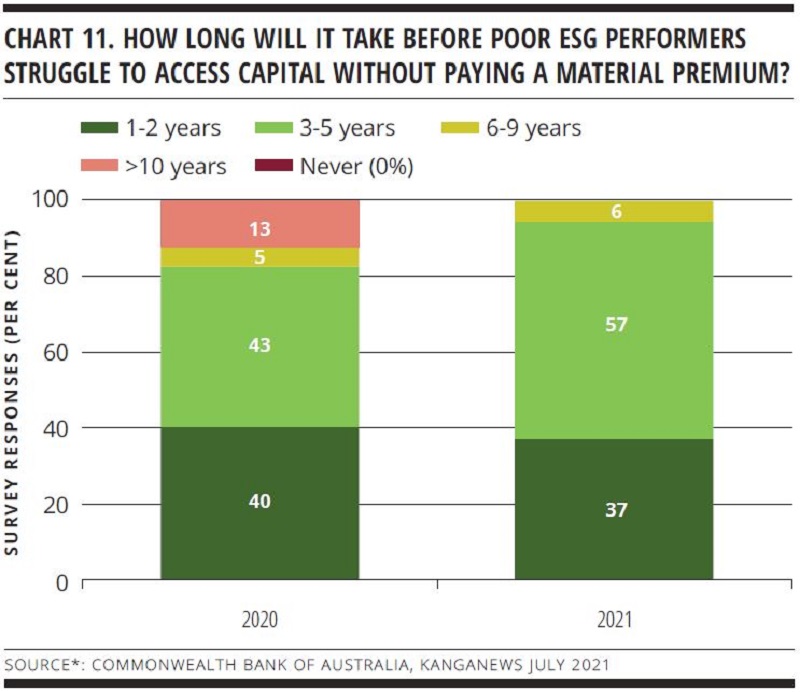

Survey data support this view, as investors suggest the remaining timeframe issuers have to access capital without paying a material premium for poor ESG performance is shortening (see chart 11). Some 94 per cent of respondents believe time will run out within five years and 100 per cent predict it will be within the next decade.

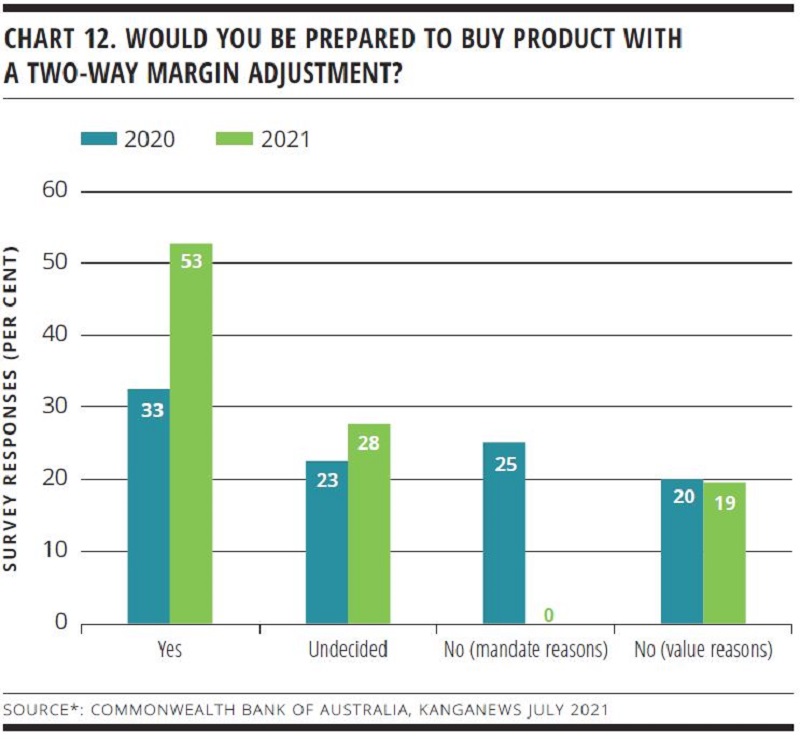

Survey data also demonstrate the extent to which the buy side is willing to share the cost of market evolution. More than half of investors say they would be prepared to buy a bond or loan product with a two-way margin adjustment provided ambitious targets are met, while the corresponding cohort in 2020 was just 33 per cent.

Mandate evolution is also at play, as no investors say they are unable to participate in sustainability-linked instruments for mandate reasons in 2021, compared with a quarter in 2020 (see chart 12).

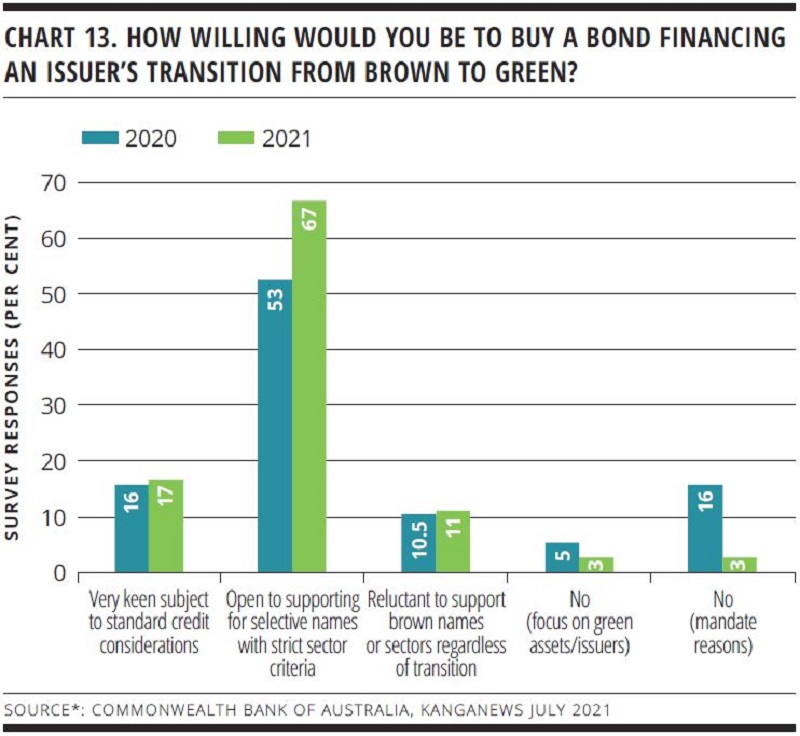

Investors are noticeably more willing to explore options for transition finance in 2021. For example, 84 per cent of survey respondents say they are either “very keen” or “open to” supporting brown-to-green transition instruments in 2021 (see chart 13).

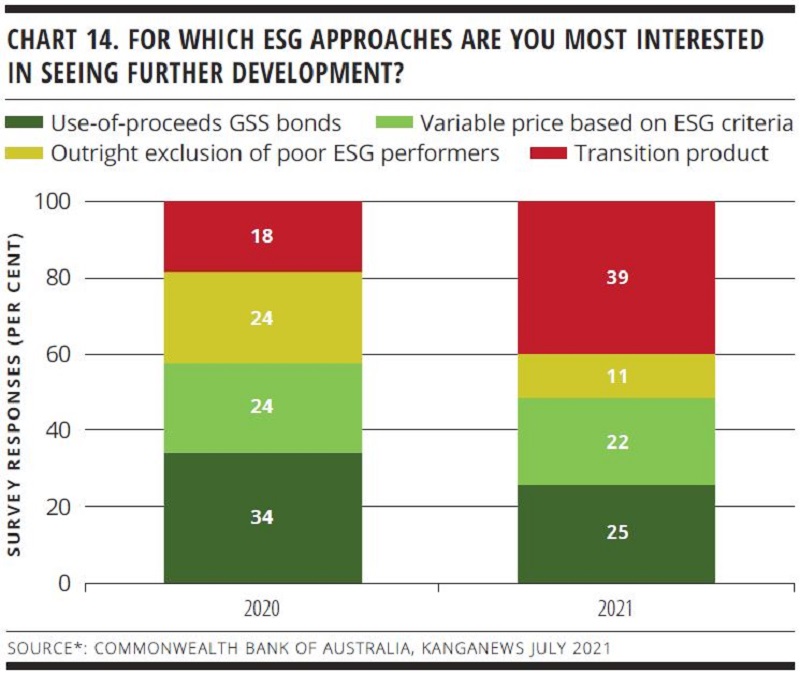

In an almost complete reversal of the survey outcomes from 12 months earlier, transition-based products feature highly on the list of investors’ most preferred ESG approaches for further development, while they seem less confident in the future growth of labelled GSS product.

In 2021, the proportion of investors interested in development of transition instruments has almost doubled, while those keen to see further growth in GSS bonds has fallen by around a third (see chart 14).

Supply may be having an impact on UOP issuance. “What is holding the market back is the lack of underlying projects for UOP bonds – there are simply not enough wind farms or solar parks to back UOP bonds domestically,” Bishay argued. “I think we will see significant growth in the SLB [sustainability-linked bond] market because the proceeds fund general corporate activities and do not require ringfencing of specific, predetermined projects. This is easier for most companies.”

Before the SLB market in Australia can thrive, however, investors suggest that greater clarity on some aspects is needed. They are willing to lend a hand in this development.

“Recent GSS deals have been at least 2-3 times oversubscribed and the situation is not helped by the fact investors have tended to buy and hold – so it is proving difficult to find stock in the secondary market.”

Button TextChrystal said at the roundtable discussion: “In advance of the launch of an SLB, dealers could provide a range of potential targets the issuer might embed into a transaction and investors could offer their views on which are going to be most relevant. This would avoid a situation where, for example, one KPI is not deemed as ambitious as another. It would also improve engagement and keep the market moving in the direction we clearly all want it to head.”

Byrne added: “The investor voice is clearly critical in the development of the SLB market. In a general sense the most important point is communication and the fact that there does not need to be a deal in or coming to the market for this communication to start. What we need is ongoing dialogue, particularly when it comes to new types of transaction structure.”

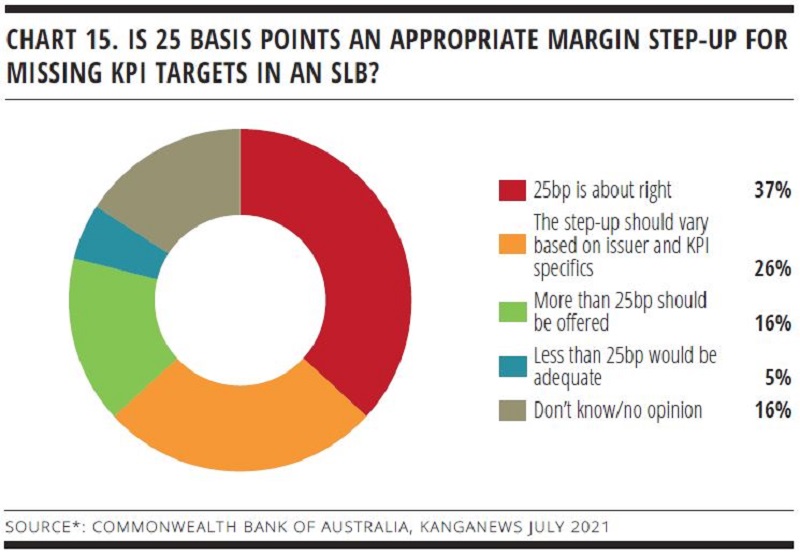

On the issue of pricing, the global market has in recent months coalesced around a norm of 25 basis points as the appropriate margin step-up for issuers that miss KPI targets included in their SLBs. The view that this is an appropriate penalty appears to be supported by Australian investors responding to the survey, with the highest proportion believing this level is “about right”. Nonetheless, more than a quarter think that more than 25 basis points should be offered (see chart 15).

Sovereign-sector specifics

The challenges of evaluating the management of material environmental, social and governance risks extend across sectors. Some investors argue they are even more pronounced in the sovereign space than they are in the credit market.

As a fund manager focused primarily on high-grade assets, Ardea Investment Management believes the prominance of government issuers in the overall fixed-income investment universe makes standard environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices, like withholding capital based on negative screening, a very different equation outside the pure credit sector.

Ardea’s principal, Tamar Hamlyn, explained at the Commonwealth Bank of Australia-KangaNews roundtable that when ESG risks are narrow and specific – as is typically the case for corporate issuers – it is relatively straightforward to integrate them into investment processes. Fund managers simply map the business activity that incurs the ESG risk, applies its own filters and screens the issuer in or out.

It is far more challenging in the high-grade sector. “At the most extreme end are governments, which engage in a broad range of activities. Some of these might be perceived as very detrimental from an ESG perspective, while many others may not be perceived to be detrimental at all,” Hamlyn explained. “The binary, negative-screening, approach doesn’t lend itself well at all where there is more nuance.”

The matter is further muddied by overlaying the size of the government-bond market globally. As Hamlyn pointed out, sovereign-sector issuance accounts for around two-thirds of fixed-income market capitalisation.

“With significant issuance coming from a handful of government issuers, making a blanket decision to exclude an entire country can change the risk-return profile dramatically. This becomes even more difficult as an Australian investor, given how poorly Australia scores on ESG. If we were to exclude our own government issuer it could create a lot of challenges.”

The fact corporate borrowers are able actively to manage the nature of their business based on ESG is another advantage not afforded to the public sector. “We have seen larger companies spin off areas of their businesses that might score poorly from an ESG perspective. Not every issuer is able to do this, although green-bond structures can help,” Hamlyn commented.

In relation to high-grade issuers, Hamlyn continued: “We are not convinced one can actually ever spin off the poorly scoring arms of governments, for example the taxes associated with resource or gambling revenues. Inevitably, there is the same fundamental underlying issuer risk. Even where there is a separation through a formal packaging of labelled bonds, as investors we ultimately think we still need to be viewing this at issuer level. We can’t just close our eyes to other risk aspects of the issuer simply by buying its labelled bonds.”

With only a handful of government issuers, making a blanket decision to exclude an entire country can change your risk and return profile dramatically. This becomes even more difficult, given how poorly Australia scores on ESG. If we were to exclude our own government issuer from our own market this could create a lot of challenges.

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.