Nonbanks make hay but contemplate season change

Australia’s nonbank financial institutions have enjoyed an unprecedented domestic funding bonanza in 2021 as circumstances have aligned to provide all-time record securitisation volume and the best pricing conditions since the financial crisis. Book growth and the return of competing supply mean the search for new liquidity pools is likely to move back up the agenda soon, however.

Laurence Davison Head of Content KANGANEWS

Securitisation has historically been the primary means of funding for nonbank lenders. The structured-finance asset class gives nonbanks access to institutional debt finance at a price that, in most market conditions, allows them to remain cost-competitive with authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) in the nonbanks’ focus lending areas.

Bank-provided securitisation warehouses typically offer nonbanks their working capital, while several supplement structured-finance facilities with alternative funding options. La Trobe Financial, for instance, funds roughly half its A$13 billion (US$9.6 billion) of assets through its retail credit fund. Meanwhile, Liberty Financial has an investment-grade credit rating and is a relatively frequent issuer in the unsecured bond market – albeit for much less volume than it prints from its securitisation programmes.

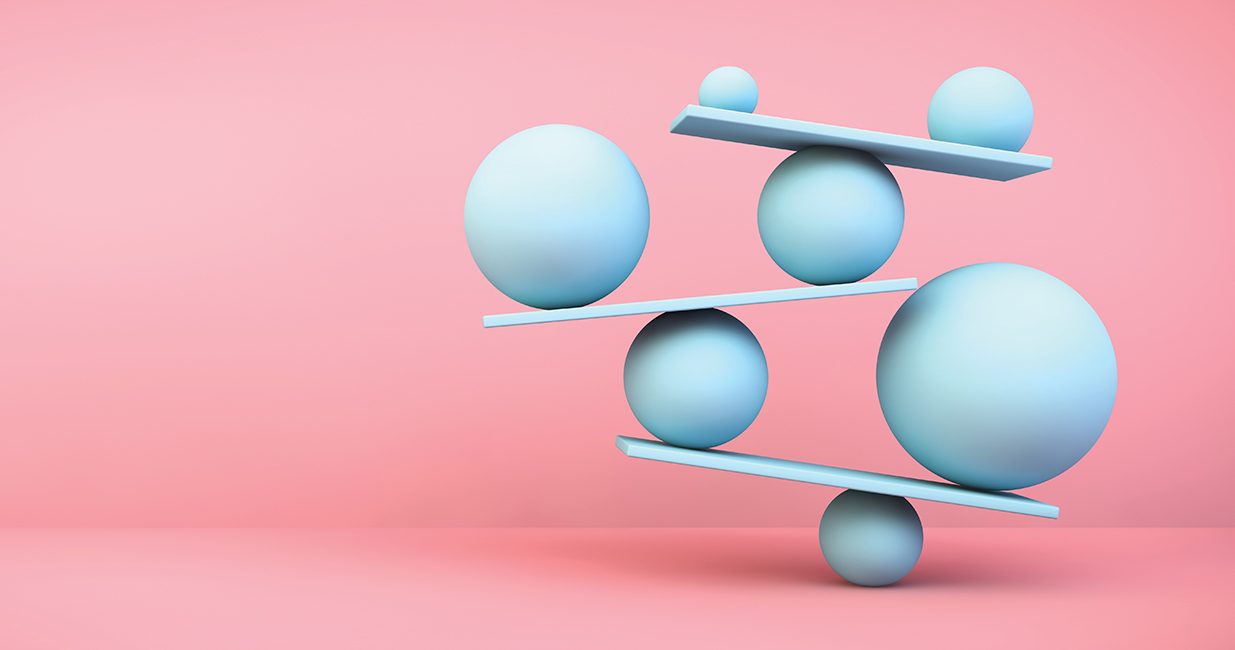

Nonetheless, public securitisation issuance is the main thoroughfare for nonbank funding – and 2021 has been a 14-lane superhighway. By mid-September, Australia’s nonbanks had printed A$26.5 billion of new residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) and other asset-backed securities (ABS), adding more than A$10 billion to the year-on-year run rate and almost trebling the full-year issuance total from as recently as 2016 (see chart 1).

The market has grown more diverse, too. The first eight-plus months of 2021 saw 24 different nonbank entities bringing transactions to the Australian dollar securitisation market, an annual record and a fourfold increase on the post-crisis low from a decade previously.

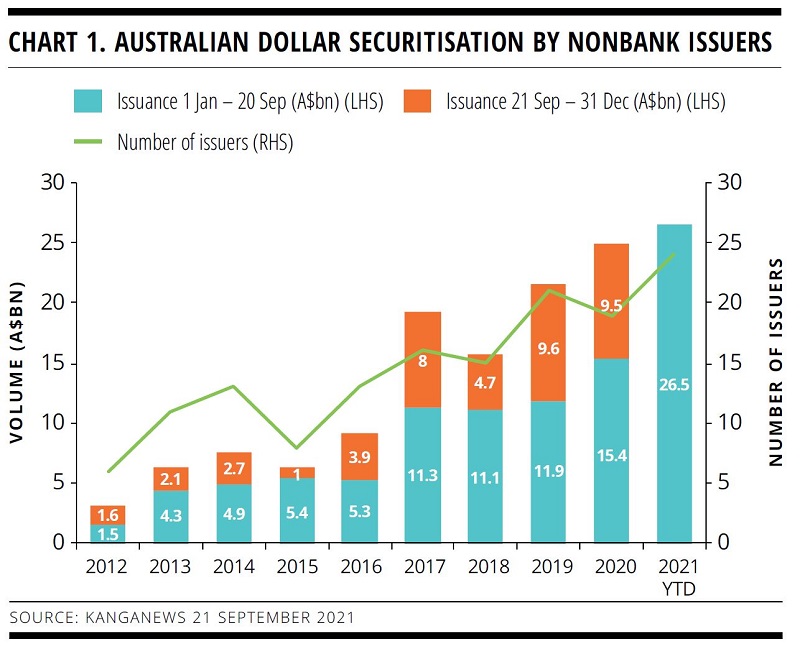

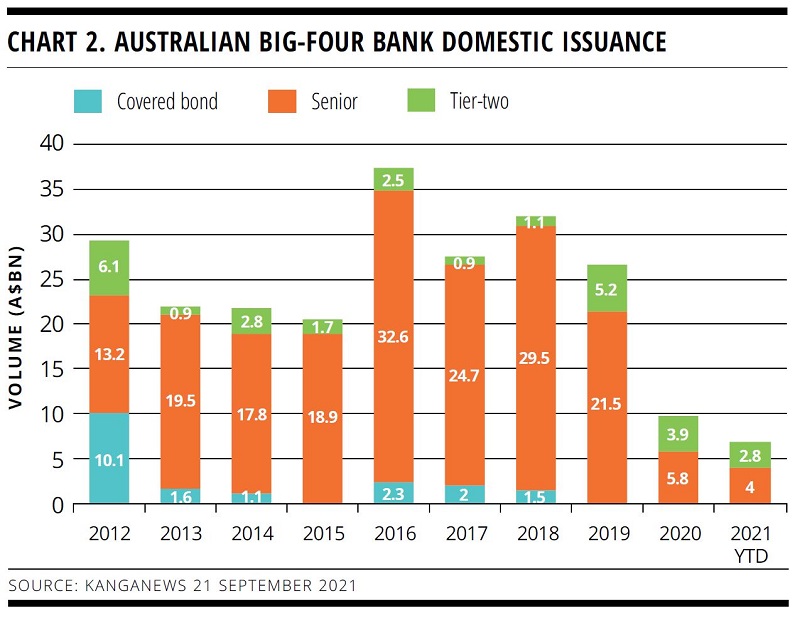

To put the scale of nonbank securitisation in perspective, the sector issued as much in 2021 to mid-September as the Australian big-four banks – traditionally the mainstay of all local credit issuance – did in the unsecured bond market across the entirety of their last pre-pandemic funding year, 2019 (see chart 2). ADIs have also been much less active as securitisers: there have been a handful of transactions from issuers outside the big four but the floor has largely been left clear for nonbanks (see chart 3).

The bank issuance profile is a major component of the positive nonbank issuance story. The onset of COVID-19 saw a dramatic shift in ADI funding dynamics, as central-bank support and a savings spike largely nullified the banks’ need for wholesale senior debt. There was not a single big-four bank senior term deal in Australia between January 2020 and August 2021.

Nonbanks have been happy to help fill the gap with their securitisation issuance. “I think the absence of competing issuance has been the single biggest positive factor in the nonbank securitisation market,” says Sarah Samson, head of securitisation origination at National Australia Bank (NAB) in Melbourne. “We have seen investors that have never participated in this market before buying RMBS and ABS, purely because they have cash and they have to allocate it somewhere.”

This has promoted a boom in Australian dollar nonbank securitisation issuance – and it is not just a domestic investor story. Fabrice Guesde, Hong Kong-based head of credit markets and global structured credit solutions, Asia Pacific at Natixis, adds: “With global QE, no ADI issuance and persistently high CPRs [conditional prepayment rates], investors have been flush with liquidity. Even some of the longstanding Japanese investors that used to invest only in ADIs have been forced to look elsewhere because they simply cannot find that paper. This has been a big driver of the nonbank market.”

There are factors at play beyond lack of competing supply, however. At a fundamental level, many years of work conducted in the wake of the financial crisis to persuade investors – at home and abroad – of the resilience of the Australian securitisation product appear finally to have paid off.

In some respects, the pandemic may have helped – by providing another stress test that Australian nonbanks have, so far, navigated with some comfort. The first wave of lockdowns in the second quarter of 2020 led to widespread predictions of a housing-market crash, soaring unemployment and an inevitable collapse of credit quality. Assisted by direct and indirect government support and a relatively quick economic rebound, the catastrophe has not come to pass.

Comfort appears to have taken deeper root in the credit investor universe over recent years. Intermediaries agree there has been no push-back on the Australian credit story, for instance.

The general view is that domestic and offshore investors have taken significant comfort that Australia has come through the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis and is so far coming through the latest round of lockdowns without developing significant hardship.

Kelly Mantova, Sydney-based head of asset-backed securities, Australia at Deutsche Bank, concludes: “Rates are low and investors are chasing spread, as well as being relatively comfortable with RMBS and ABS as a defensive asset class. The market feels strong – as strong as it has been for a long period of time.”

WINDS CHANGE

Securitisation market participants are under no illusions that the unique set of tailwinds behind issuance over the past 18 months can be maintained indefinitely. The wind is already changing in some areas.

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s term funding facility (TFF) expired in mid-2021, shutting off the supply of ultra-cheap three-year funding to the ADI sector. Indeed, by late in the third quarter of the year it is becoming clear that the big four are likely to return quite quickly to a similar quantum of wholesale issuance to what they were printing pre-pandemic.

In August, NAB printed the first big-four senior-unsecured deal in Australian dollars for more than a year and a half, issuing A$2.75 billion at five-year tenor. In a further sign that major bank issuance may be returning more quickly than anticipated, on 24 September Westpac Banking Corporation priced A$1.2 billion in a funding-only RMBS transaction – the first big-four securitisation since January last year.

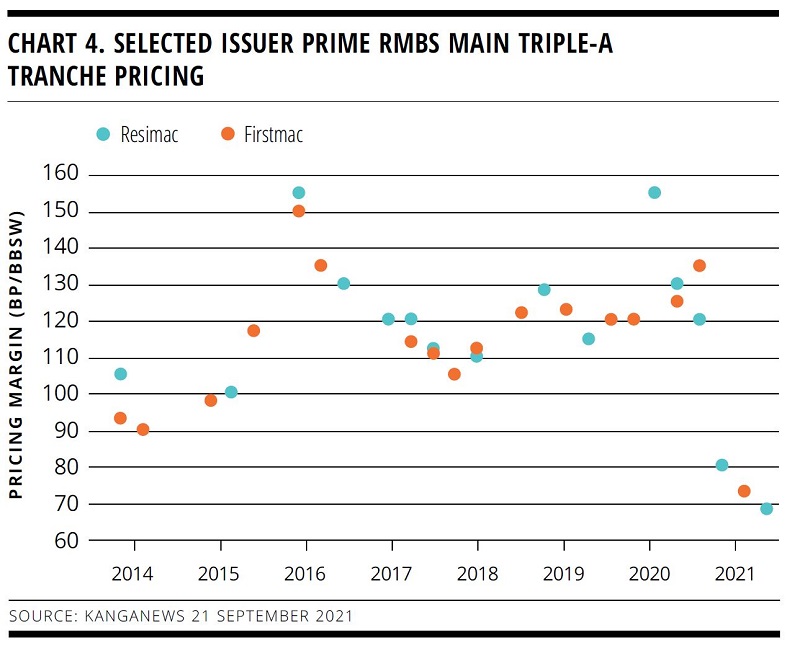

There is also a sense in the structured-finance market that spread compression may be close to the end of an extraordinary journey. As recently as late 2020, new triple-A prime RMBS was pricing in the low-to-mid 100s basis points over bank bills – as it had for the past half decade. Price compression in 2021 has seen pricing on such tranches from some of the market’s most familiar issuers fall – in some cases – below 70 basis points over bills (see chart 4).

Any suggestion of issuance fatigue remains at the margin. Bankers report, for instance, that bookbuilds for senior notes have started to take a little longer as the volume of issuance and spread compression start to have an impact on triple-A buyers. Deals generally remain very well supported, though.

Guesde adds: “We have seen a handful of investors dropping out of some deals as spreads were tightened during pricing but the transactions are still being massively oversubscribed. I think it is a question of alternatives, or lack thereof – it is hard for investors to drop out, regardless of what they think of the spread, when there is nothing else to buy.”

Even so, intermediaries are signalling that the relative-value proposition offered by Australian nonbank securitisation has eroded to a fairly significant extent, and this is having an impact on international senior-note buyers in particular. These investors typically look at a range of global product and by the later months of 2021 may be starting to see the best value outside Australia.

“Over the course of this year, we have seen spreads tighten significantly in the Australian market. This means they are now roughly in line with RMBS margins in the UK market, for example,” Mantova explains. “Investors have previously seen relative value in Australian product, especially given the quality of collateral they can find here, but this advantage has dissipated to some extent.”

There are no expectations of a rapid or significant unwind of the price-tightening trend, absent external factors or a more general turn in credit direction. Indeed, a positive read on market conditions suggests price tension remains positive and even the investors that are not fully active in Australian securitisation would likely provide support if credit margins moved even slightly wider.

Mantova, for instance, argues there is another layer of global demand including some large institutional investors that would likely come back into Australian dollar product if it offered 5-10 basis points more spread.

Meanwhile, Samson tells KangaNews: “It is often said that issuers have to choose between price and volume, but at times in the past 12 months they could genuinely have both. Very recently, the decision has become more relevant once more – but we are still talking about a differential of no more than 5 basis points to find extra bids.”

MARKET MATURITY

Even if the high-water mark of positive conditions has already passed, securitisation intermediaries are confident a deeper liquidity pool will remain after the tide recedes. The main long-term change is that supply dynamics have convinced more investors than ever to engage with the structured-finance asset class – and they are likely to retain limits to it even if their activity migrates to more of a relative-value view.

To put this in context, to some extent the Australian securitisation industry’s primary quest over the past decade-plus has been finding new investors – at home and offshore – to replace those that detonated during and immediately after the financial crisis. Credit investors neglected securitisation for a raft of reasons, from the product’s lingering post-crisis miasma of risk and opacity to more mundane factors like lack of secondary liquidity and the mandate challenges of incorporating an amortising product.

The work has been painstaking and has involved many avenues of outreach and education. There have been notable wins, for instance in the growing demand for Australian product from Japan. However, it may have taken an absence of competing supply to drive the final wave of engagement across the credit investor base.

The key factor here may be the very complexity that has been a barrier to securitisation market entry. Investors need to commit resources to things like pool-level analysis that are critical in the structured-finance space. Intermediaries hope the large number that has now made this type of commitment will not let it all be for no more than a few months of allocations.

“It is a generalisation, but not an inaccurate one, that investors are not going to do the work to come into a securitisation market and then only buy one or two deals,” says Milos Ilic-Miloradovic, executive director, global structured credit solutions at Natixis in Sydney. “Lack of competing supply has been a factor and as it comes back it is possible securitisation spreads will have to adjust. But I believe the universe of investors engaged with this market will remain enlarged.”

Samson adds: “With the banks back in the market it is likely to evolve, for investors, to more of a relative-value question – what else can they buy in the context of their overall portfolio makeup. Bank senior issuance will look attractive, in particular because there hasn’t been any of it. But I don’t think it will eliminate the new demand that has come into securitisation.”

The feeling overall is of a healthier, more sustainable market with deeper roots. The pool of investors that are at least willing to engage with issuance and will support it at the right price is deeper and – perhaps most importantly – very much wider than it ever has been.

“I think the Australian market has matured over the last three or four years,” Mantova suggests. “Previously it was beholden to a small group of investors, to the extent that if one or two of these accounts dropped out we would be concerned about general appetite for the product. We have seen a significant diversification of the investor base domestically and globally, which means issuers can now be much more sophisticated about the way they approach the market.”

LIQUIDITY AND PRICE

With this in mind, some intermediaries believe the Australian dollar market should have capacity to support an enlarged ongoing issuance task even if near-term conditions ease. “With the constant flow of redemptions and the amount of money in the system that needs to find a home, I am not immediately concerned about the volume of issuance that needs to be done – I think it can all be placed in the domestic market,” Samson tells KangaNews.

The question may not be availability of liquidity but cost of funds – on an absolute basis and relative to ADI funding, as nonbanks seek to maintain a competitive lending offering. Not only have outright securitisation margins crunched in but so has relative pricing of nonbank issuance relative to ADI spreads.

“Nonbanks still offer a yield pickup over ADIs but it has become very, very tight – and this cannot be sustainable when the banks return to issuance,” Guesde argues. “The question is where the absolute level will land. Perhaps investors remain hungry for paper such that securitisation spreads can tighten even more – or perhaps not. But at some point the relative-pricing dynamic will have to evolve.”

The early signs are that returning major-bank issuers may be able to find a cost of funds beneath the floor even of ultra-tight RMBS margins. NAB’s return to domestic senior bond issuance priced at 43 basis points over mid-swap, roughly 25 basis points inside the best margins the top tranches of nonbank prime RMBS have achieved.

Outright margins on both products are in the region of 35 basis points tighter than levels from just before the COVID-19 crisis reshaped supply dynamics, but the gap between the two is very similar. This might be good news for nonbanks, as it suggests they may be able to maintain securitisation cost of funds rather than repricing wide of the returning banks. But it also implies an ongoing cost-of-funds advantage for the ADI sector.

This would not be new, however. Australian nonbanks have learned to find growth opportunities outside the most mainstream part of the mortgage market and even coped with aggressive bank fixed-rate pricing facilitated by the TFF in 2020. Whether it be prime and nonconforming mortgage lending or the panoply of other credit products that are now being securitised in Australia, price is often not the nonbank USP.

Ilic-Miloradovic explains: “We are told that the nonbanks have been winning business based on service rather than price. If this dynamic is maintained it is possible they will be able to absorb at least some erosion of the very conducive funding environment they have been enjoying.”

SINGLE-NAME LIMITS

Even so, securitisation market participants are not taking anything for granted as the peak of funding conditions potentially starts to ebb. One area of particular focus was an agenda item in 2019 before being put on hold by the pandemic: potential single-name limits for the largest nonbanks’ securitisation issuance.

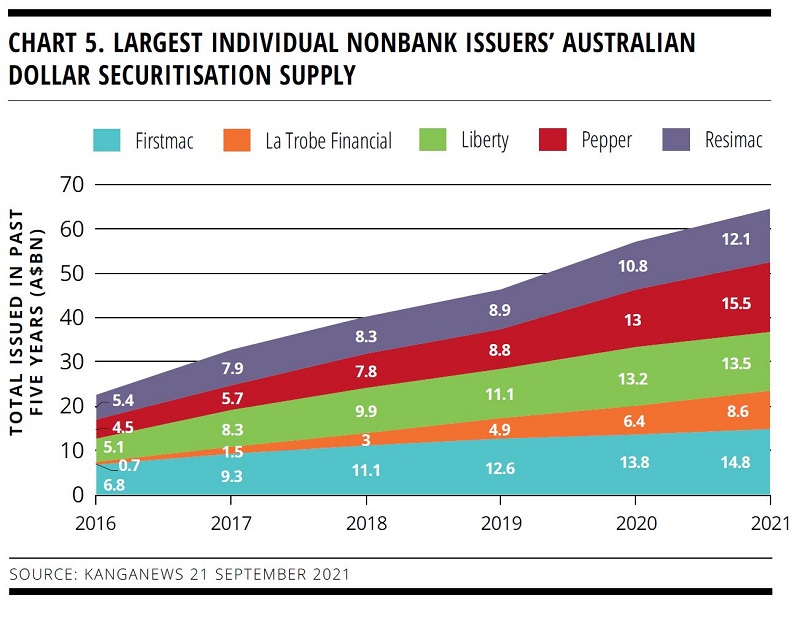

The biggest nonbanks have stepped up issuance significantly over the past half decade. Firstmac, Liberty, Pepper Money and Resimac have all had multiple years of A$3 billion or more of securitisation supply, with Pepper Money topping the single-year table with its A$5.2 billion – including refinancing – in 2020.

Before the pandemic, market sources speculated that around A$15 billion might be as much as a single nonbank could expect comfortably to maintain on issue in the securitisation market. At least two Australian nonbanks are around that level in cumulative issuance over five years (see chart 5), though transaction amortisation undoubtedly provides natural headroom.

The A$15 billion figure may never have been strictly accurate – it was never more than an estimate of a theoretical cap that was yet to be tested in action, even pre-pandemic. Whatever the actual level of single-name securitisation limits, it has also likely been inflated by the positive market evolution of recent months. However, even if larger issuers have several billion dollars of headroom they are clearly aware of the potential risk of running up against single-name limits.

So are intermediaries. Mantova tells KangaNews: “The number and scale of new investors in the market has taken some of the sting out of single-name limits, but they could quite easily come back into the conversation. Nonbanks continue to grow and, as a result, they are going to have to remain focused on what is next for accessing incremental pools of capital.”

FUNDING DIVERSIFICATION

The good news is the nonbanks that are most likely to encounter issuer-specific limits are also the ones with established access to a healthy range of alternative funding sources. These include options outside securitisation like La Trobe Financial’s retail fund and Liberty’s unsecured bond programme.

Another avenue nonbanks are exploring is environmental, social and governance-themed issuance, which should open up access to new pools of liquidity held by new and existing investors (see box).

ESG growth primarily an asset story for nonbanks

Issuance with an environmental, social and governance (ESG) theme could be a godsend to nonbanks seeking incremental funding liquidity, and many are keenly pursuing opportunities to bring green or even social securitisations to market. The biggest challenge is likely to be finding sufficient volume of qualifying assets to support issuance at scale.

Issuers of ESG-aligned debt instruments tend to say access to incremental liquidity, rather than superior pricing, is their primary motivation for coming to market in this format. Australia’s nonbank securitisation issuers are arguably the only sector of the local institutional credit market for which access to sufficient volume of debt financing is even a live consideration – so ESG should be a natural fit.

Green, social and sustainability (GSS) issuance is clearly of interest. Consumer-finance lenders like Brighte and hummgroup have included green-labelled tranches in their asset-backed securities issuance, largely backed by loans taken out to buy and install household solar facilities. Meanwhile, Firstmac privately placed A$750 million (US$556.1 million) of green residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) in June 2021.

The most widely tapped well of additional funding liquidity, however, has historically been foreign-currency securitisation. The red-hot domestic market has made foreign-currency issuance economically unattractive of late, but at its peak – in 2019 – it provided approximately A$2.5 billion equivalent of incremental liquidity to Australian nonbanks or more than 10 per cent of the sector’s total issuance for the year.

There is little doubt about demand for Australian securitisation denominated in foreign currencies. “Foreign currency issuance is the natural place to go especially for issuers that are coming up against single-name limits,” Mantova continues. “A lot of new investors either have done or are doing the work to understand the Australian market. But the same message comes through consistently from a number of offshore investors: if these issuers could do transactions in US dollars or other foreign currencies, ticket sizes could be many times larger than they are now.”

The primary challenges are economic. The cost of cross-currency hedging has made for an unattractive landed cost of funds for many months, a hurdle that has only been heightened by the relative cost of swaps when set against skinny outright issuance margins. Australian issuers are also – understandably – reluctant to be early movers in international markets that are going through the process of LIBOR transition, Samson suggests.

Most intermediaries expect a return to foreign-currency issuance will happen if the pricing gap closes even to the point where a small premium is required to transact offshore.

“In general, issuers that have been active in foreign currencies are keen to return when the economics stack up,” Samson comments. “They have worked very hard to build relationships with investors that include commitments to programmatic issuance that they want to honour. There have just been headwinds offshore and tailwinds domestically that have promoted a home-market focus for the past 18 months.”

This sort of engagement is likely to prove to be a wise course of action over the years ahead. Guesde says: “Liquidity and issuance volume have been amazing, and lots of issuers have taken advantage. But this means there is a big refinancing wave coming up in 3-5 years. The optionality issuers get from calls is very important, but ultimately this refinancing will need to be worked out – and issuers cannot simply assume the domestic market will provide the liquidity they need.”

nonbank Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's eighth annual guide to the business and funding trends in Australia's nonbank financial-institution sector.

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.