Knock-on effects

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s decision to reduce the size of the committed liquidity facility to zero by the end of next year may not be entirely surprising but it has ramifications across the local fixed-income market. The most obvious are on the demand side, but a closer examination of the decision’s implications also reveals likely consequences for supply dynamics.

Laurence Davison Head of Content KANGANEWS

The committed liquidity facility (CLF) was created to solve a specific problem, namely the insufficient supply of qualifying high-quality liquid assets (HQLAs) in Australia to meet the much larger aggregate needs of local authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) – particularly the big-four banks – under tighter liquidity regulations brought in following the global financial crisis.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) determined relatively early in the post-crisis re-regulation process that only domestic sovereign and semi-government bonds met the criteria to be considered HQLAs for the purposes of liquidity-coverage ratio (LCR) rules. It has not changed its opinion over the subsequent years.

The regulator said other securities that might have made the grade – most notably bank covered bonds and supranational, sovereign and agency (SSA) Kangaroo bonds – did not clear its threshold of acceptable market liquidity in stressed conditions. The problem was that the supply of HQLAs on issue was not sufficient to satisfy the banking complex’s LCR needs without a severe impact on liquidity in the open market.

The CLF came into the breach to solve this shortfall in assets. APRA required banks to hold as much of their liquid-asset books as possible in HQLA format – initially up to an aggregate of 30 per cent of total outstanding volume of HQLAs, a ratio determined by the Reserve Bank of Australia. For the rest, the banks were permitted to hold a CLF with the reserve bank, comprising other repo-eligible securities including SSA and covered bonds, bank senior debt and securitisation of their own and other banks’ assets.

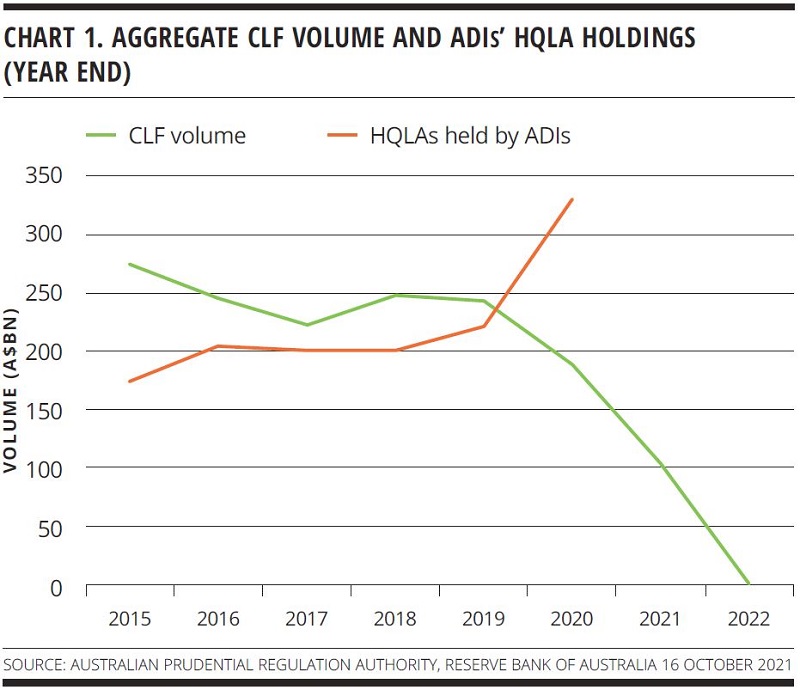

Initially, the CLF needed to be substantial. It was A$275 billion (US$197.5 billion) in aggregate in 2015 and remained more than A$200 billion until 2020, even increasing marginally in 2018 (see chart 1). More recently, the avalanche of government-sector bond issuance triggered by the COVID-19 response has taken the scale of the HQLA market to a new level and eased the pressure on banks’ HQLA holdings.

While the most significant period of sovereign-sector borrowing growth may have passed, the increase in volume of available HQLAs is set to continue. Liquidity regulation is based on the volume of such issuance outstanding rather than growth in net new issuance, and while the Australian Office of Financial Management’s issuance task has eased since the depths of the pandemic, it is still expected to be adding to the stock of bonds on issue rather than retiring debt for the foreseeable future.

There is even an amplification effect in evidence. Not only is the volume of HQLAs on issue much larger but the RBA has grown confident banks can comfortably hold a larger proportion of this market. It has increased the share of government and semi-government securities it believes can be held in the banking system to 35 per cent of the total, from the previous 30 per cent. This increase alone accounts for an additional A$65 billion of available HQLAs based on year-end 2020 figures from the reserve bank.

The RBA now estimates the Australian banks will be able to hold an aggregate of A$563 billion of HQLAs in calendar 2022, based on estimated volume on issue of A$1.1 trillion of sovereign bonds and A$530 billion of semi-government securities.

IMMEDIATE CONSEQUENCES

The decline in scale of the CLF will inevitably influence the shape of the Australian dollar bond market. In theory, the impact will be huge. Analysts estimate roughly A$100 billion of CLF assets comprise internal securitisation – ADIs’ own loans packaged as repo-eligible structured-finance securities – and the remaining A$40 billion is cash bonds issued by other entities.

The former will need to be replaced outright, and the latter sold down or replaced at maturity – though much of this volume will comprise securities with maturity dates after the end of 2022.

However, there is little or no expectation of a radically higher bid for HQLAs driven by the banks accelerating the process of accumulation to replace the CLF, and even less of a dramatic selldown in assets previously held in the CLF.

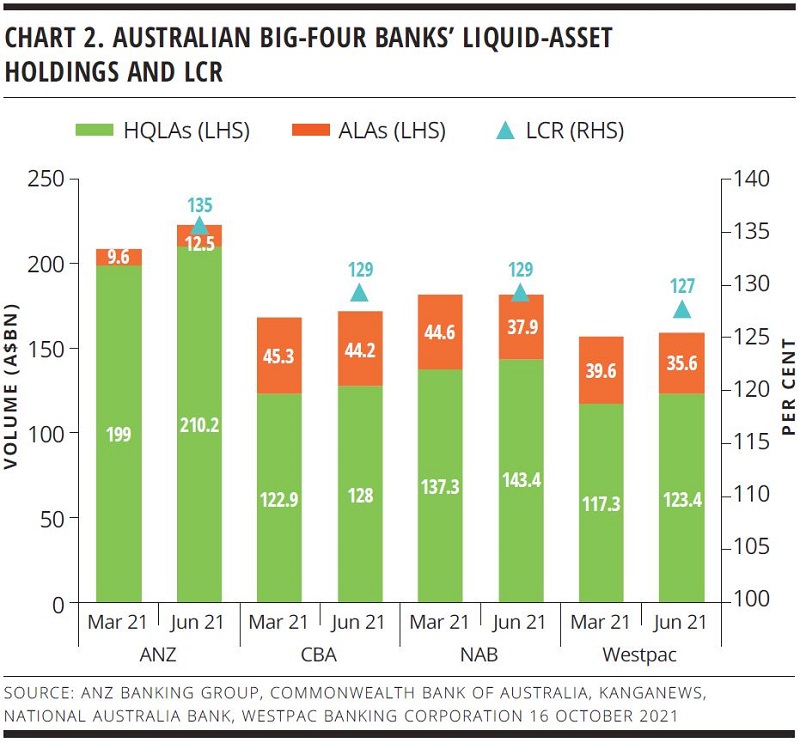

For one thing, the big-four banks are all running LCRs that are not just comfortably higher than the regulatory minimum but also well above their own typical level (see chart 2).

“At the moment, the system is close to 130 per cent LCR but historically it is close to 123 per cent – particularly for the major banks,” says Brendon Cooper, head of credit and ABS strategy at Westpac Institutional Bank in Sydney. “If we simply set the eight largest CLF banks’ LCR at 123 per cent rather than where it actually sits at present, we free up close to A$60 billion of capacity. There is quite a bit of wriggle room, and I don’t see why the system would operate at a level particularly above the historical norm.”

The other key mitigating factor to a major realignment of demand and medium-term buying patterns is the elevated scale of the RBA’s exchange settlement (ES) account. The volume of ES funds has also exploded during the pandemic, from tracking almost exclusively in the A$20-30 billion range on aggregate from late 2013 to February 2020, to a new record of more than A$400 billion in October this year.

In its CLF announcement, APRA notes it is basing its conclusion that the facility is not required in the current environment on the combined volume of HQLAs and ES balances expected in 2022.

This answers another question about the decision: the fact that the RBA’s projected level of HQLA volume for 2022 still does not comfortably meet the likely LCR requirements of Australian ADIs. Indeed, according to regulatory disclosures, the big four alone were holding more than A$600 billion of HQLAs at the end of June 2021.“A key takeaway is therefore that ES balances have transitioned from not being considered for liquidity purposes when APRA set its 2020 LCR guidance, to being key for the current outcome,” Cooper says.

QE, and the mechanism by which it is executed, may be the key to this change. Banks acquire sovereign and semi-government bonds at auction and then sell them down to the RBA, with ES balances created by these transactions. This likely goes at least some way to explaining why HQLA holdings are so elevated and why APRA now considers the ES account to be a key component of its liquidity regime.

“There is now a large question mark over the ability of the Australian dollar market to provide a consequential proportion of the volume of term funding the banks need. If the liquidity books don’t buy their peers’ deals in the same size as before, I can’t see how the local market maintains its previous scale.”

MEDIUM-TERM IMPACT

This does not mean there will be no market impact from the CLF decision, however. Analysts expect bank liquidity-book investors will change their behaviour, at least at the margin.

Philip Brown, senior interest-rate strategist at Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) in Sydney, agrees that the latest RBA bond-purchase programme, and the ES it generates, should be able to replace the CLF. “This does imply, though, that banks would need to keep hold of all their other current HQLAs, so the recent process of ES balances displacing other assets in the liquidity stack will likely evolve,” he adds. “If banks are no longer selling ACGBs [Australian Commonwealth government bonds], the RBA will need to convince other sellers to part with their ACGBs – which may require higher prices.”

The other side of the same coin is the outlook for bank demand for issuance that would previously have been included in the CLF. In recent years, Australian ADIs have been major supporters of each others’ domestic issuance in senior and residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) format, primarily because such assets supported their LCR via the CLF.

“There is now a large question mark over the ability of the Australian dollar market to provide a consequential proportion of the volume of term funding the banks need,” suggests Gerard Perrignon, managing director, debt capital markets at RBC Capital Markets in Sydney. “If the liquidity books don’t buy their peers’ deals in the same size as before, I can’t see how the local market maintains its previous scale.”

This theory that domestic bank deals will not be as large in future is largely untested by mid-October 2021, though issuance trends are so far not contradicting it. The big-four banks have only recently returned to senior issuance after the end of the RBA’s term-funding facility (TFF), and the first domestic senior-unsecured benchmark deal – of A$2.75 billion, from National Australia Bank – came before the CLF announcement.

CBA’s first domestic benchmark of 2021, priced on 17 September, was for just A$500 million. But this was in green-bond format and the issuer noted its conservative approach to the underlying asset pool. Meanwhile, Westpac Banking Corporation returned to RMBS issuance on 24 September – and market commentary focused on the deal’s relatively small size: A$1.2 billion, compared with A$3 billion when it last came to the securitisation market in February 2020. Westpac was pleased with the number and quality of investors it attracted, however.

Perhaps the biggest clue to the big-four banks’ thinking on domestic liquidity is the rate at which they are returning to offshore issuance compared with relatively thin Australian dollar flow. Since the end of the TFF, the big four have printed the equivalent of approximately A$10.1 billion of senior and covered bonds in foreign currencies, and A$4.6 billion of senior bonds and RMBS domestically.

This might not indicate a major funding-strategy rethink on the major banks’ part: pre-pandemic, a decent rule of thumb was that they might as a group expect to fund roughly one-third of their wholesale need domestically. But the fact that there has only been one large domestic benchmark print – compared with at least four offshore, including covered bonds – might be an indicator of a change at the margin.

A larger banking-sector funding gap would likely have consequences for the Australian dollar credit market. Heightened outbound issuance flow would have a structural impact on the cross-currency basis swap, for instance – which would add a tailwind to incoming issuance that might prove to be a boon for the Kangaroo market.

FUNDING CONSEQUENCES

The CLF could have a double impact on bank funding, reducing domestic demand while at the same time giving ADIs a new issuance need. Analysts point out that internal securitisation is of assets already on banks’ balance sheets and therefore does not need to be separately funded. Meanwhile, most expect the banks to run down – or even maintain – their external CLF security allocations rather than actively selling them.

Referring to CLF assets as “HQLA2”, Brown says: “The banks currently own HQLA2 to present to the CLF. At present that HQLA2 is very large – but it’s mainly internal RMBS. There may be some selling pressure as the banks neaten and lighten their load of HQLA2, but a lot of the HQLA2 is assets that represent the core business of the major banks – namely self-securitisations. Banks owning RMBS is also useful diversification. So HQLA2 still serves a purpose even if no longer needed for the CLF.”

This implies the replacement of more than A$100 billion of CLF holdings with HQLAs will have to be funded. The banks are already returning to term-funding markets in larger size than most expected even shortly before the end of the TFF, and they also have approximately A$180 billion of TFF maturities to refinance by June 2024. The economic recovery, meanwhile, also has positive signs for credit growth.

Speaking at the recent ANZ-KangaNews trading roundtable, Stephen Butcher, executive manager, balance sheet management at Suncorp in Brisbane, acknowledged: “There is a funding implication and a relative spread implication in the amount of assets used as collateral for the CLF… We will be moving from relatively higher-spread to lower-spread products and, at the same time, we are going to have to issue in some shape or form.”

Banks are keen to insist the impact should be limited and more than manageable. Butcher argued that, far from experiencing subdued demand, wholesale funding markets globally have more capacity for bank issuance than ever. Perhaps even more importantly, savings rates and ES balances put the banks in a completely different balance-sheet position now than they were in at the start of 2020.

In a statement provided to KangaNews, Westpac says: “We acknowledge there are funding implications for the bank in the announced phasing out of the CLF and we are working through this. Fortunately, over the last couple of years the changes in our balance-sheet composition and high levels of market liquidity have given us some flexibility in how we approach this. An increased proportion of deposits in the funding mix, a lower funding gap, capacity in our short- and long-term funding outstandings, and constructive global markets are all important considerations when we think about transitioning away from the CLF.”

The main theme that comes through from ADI balance sheets and analysts is that CLF transition is a work in progress, the full consequences of which will only become known over time. Banks admit in private that the APRA announcement took them by surprise, but by the same token most commentators say the end of 2022 deadline for zero CLF should allow plenty of time to work through the process.

Butcher concluded: “I think the banks are well positioned. But there would be more pressure on markets if the savings rate drops dramatically at the same time as TFF maturities and banks having to refinance with a lot more issuance.”

In this case, there is at least some hope that the regulators would act. CLF volume was always flexible, and some market participants note it could be reintroduced as easily as it was withdrawn – and likely would be, especially if the ES component of LCR coverage dropped precipitously.

There is even some speculation that a formal HQLA2 regime could come back onto APRA’s agenda in the years ahead. In other words, the regulator could choose to supplement sovereign and semi-government bonds not with a revived CLF but with an official range of additional HQLAs.

This seems an unlikely outcome, given the basis for APRA’s initial rejection of a wider HQLA list – lack of market liquidity – has likely not changed in the past decade. But it could resolve any future challenges without needing the CLF to be revived.

HIGH-GRADE ISSUERS YEARBOOK 2023

The ultimate guide to Australian and New Zealand government-sector borrowers.

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.

SSA Yearbook 2023

The annual guide to the world's most significant supranational, sovereign and agency sector issuers.