Move on up

New Zealand inflation reached its highest point in more than 30 years at the end of 2021 but wage growth has not taken off in a similar manner. Analysts believe wages will catch up but fear this will trigger a wage-price spiral, further fuelling inflationary pressures.

Chris Rich Staff Writer KANGANEWS

For much of 2021, many analysts continued to argue that rising global inflation was transitory – the product of disrupted supply lines and the public health response to COVID-19 rather than a resurgent force in global markets. New Zealand may have been the first country in the world, and was certainly among the first, to tip the balance of probabilities toward expectations of protracted higher inflation.

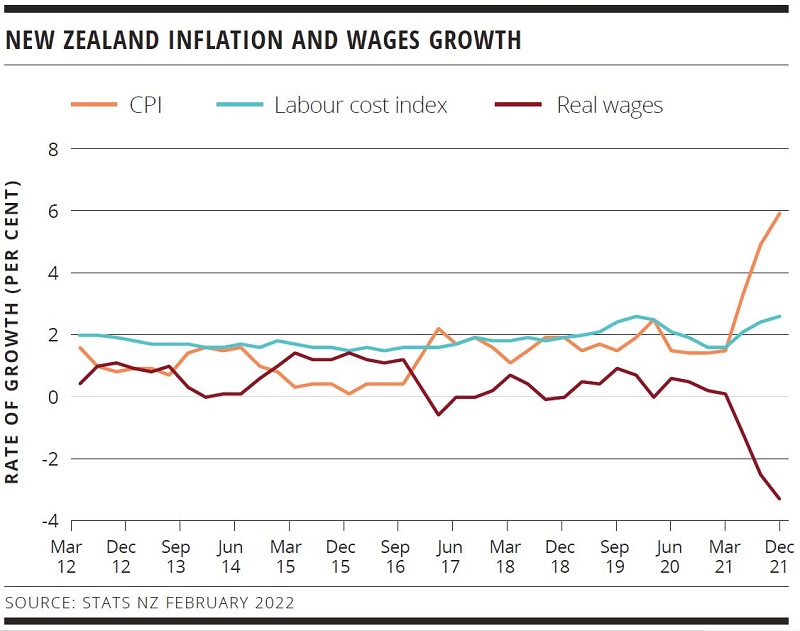

It may be too early to say definitively that New Zealand is in a prolonged period of higher inflation, but the December 2021 CPI print was the third in a row of more than 3 per cent (see chart) and, at 5.9 per cent, was the highest quarterly level since 1990.

There have been other inflation spikes in recent memory, most recently in 2011 when CPI also ticked above 3 per cent for three consecutive quarters including peaking at 5.3 per cent. Two key differences a decade ago were that inflation was already subsiding by the third relatively high print, and that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) did not feel compelled to respond: the official cash rate (OCR) stayed on hold at 2.5 per cent throughout 2011.

The reserve bank has already responded to the latest inflation surge. It halted bond buying under its large-scale asset purchase (LSAP) programme in July 2021 – well ahead of many of its peers including the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), which only announced the end of its QE programme in February this year. The RBNZ likely would have raised the OCR in its August 2021 monetary policy statement if a COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown the day prior to the decision had not stayed its hand.

Even so, the RBNZ raised the rate twice, in October and November, by 25 basis points to take the OCR to 0.75 per cent. Analysts universally expect the central bank to keep increasing the cash rate over the course of 2022. The consensus expectation is for it to reach at least 2.5 per cent this year and perhaps to peak at 3 per cent in 2023.

The RBNZ is also publicly discussing reducing the size of its balance sheet – a further tightening measure. Where the RBA seems to favour allowing its QE holdings to run down naturally and may even reinvest some of them, the RBNZ is making noises about actively selling at least some of its LSAP holdings.

INFLATION OUTLOOK

There is still some expectation that inflation inputs from stressed supply chains will ease over the course of 2022, which may see CPI dial back. In this context, the primary concern for the RBNZ in 2022 is the potential feedback loop between surging inflation and an extremely tight labour market.

BNZ analyst forecasts from January 2022 expect Q1 2022 CPI to hit 6.2 per cent before easing to 3.1 per cent by year end and 2.4 per cent in late 2023. This is predicated on the expectation of an active RBNZ that prioritises the battle to get CPI back to the 1-3 per cent target range. “Core measures of inflation, wage inflation and general inflation expectations are prone to signal CPI inflation remaining above rates consistent with RBNZ mandates,” BNZ research argues.

In its November monetary policy statement, the central bank outlined the risk that high inflation outcomes will lead to an increase in expected inflation that becomes embedded in wage- and price-setting behaviour. In this respect, while the inflation spike has, so far, only been ongoing for three quarterly prints the clock is clearly ticking on the embedding of higher inflation expectations in the wider economy.

“We currently assume these impacts will be limited, as we expect observed annual inflation to decline from the middle of next near,” the RBNZ says. “However, there is a risk that inflation remains higher on balance than in the central projection and leads to high inflation becoming more embedded.”

This prospect received a boost in likelihood following the latest CPI print given the RBNZ anticipated just 5.7 per cent inflation.

The real issue is that inflation is clearly no longer being driven solely by disruption to global supply chains, according to ANZ research published in January. The domestic economy is highly inflationary, demonstrating that inflation has spread from a few transitory factors related to the pandemic into a surge in prices across the consumption basket.

“These are troubling numbers for a central bank that has only just embarked on its hiking cycle – even if the RBNZ has been quicker than many international peers to recognise the change in the wind and raise rates,” ANZ analyts write. “There is more work to do in order to bring the surging domestic inflation impulse under control – and that will weigh on an economy that’s already struggling to grow in the face of ongoing COVID-19 disruption.”

“The issue is not that wages have not kept pace with inflation. Instead, what is puzzling is that wage growth has not picked up as much as we would have expected given the tightness of the jobs market.”

Button TextLABOUR MARKET

Less than a week after the December CPI print, labour market figures surpassed market expectations as well. The unemployment rate dropped to a record low 3.2 per cent for Q4 2021, from a downwardly revised 3.3 per cent in Q3. The rate reached its COVID-19 peak in Q3 2020, at 5.3 per cent.

However, wages have not kept up with the pace of inflation. The labour cost index (LCI) – all salary and wage rates, including public and private sectors – rose by 0.6 per cent in Q4 for an annualised rate of 2.6 per cent, or less than half the annualised inflation rate. Real wages have declined over the last three quarters and created significant cost of living pressure for many New Zealanders.

To date, even the higher wages growth seems like little more than a catch-up after limited pay rises in 2020 in the wake of the pandemic’s initial shock, according to Westpac New Zealand’s Auckland-based chief economist, Michael Gordon.

Given a large portion of the recent spike in inflation has been driven by a global cost shock caused by COVID-19 disruptions, Gordon says: “The issue is not that wages have not kept pace with inflation. Instead, what is puzzling is that wage growth has not picked up as much as we would have expected given the tightness of the jobs market.”

While nominal wage and salary inflation has not tracked with the CPI over 2021, BNZ analysts believe the disparity will redressed in the year ahead as the lag to renegotiate pay catches up. “[We expect] nominal wage inflation continuing to grind higher and CPI inflation coming down to 3.2 per cent during 2022. This process will be underscored by the ongoing tightness in the labour market, meaning employee demands for cost of living compensation have a good chance of being met.”

The concern is that wages growth accelerating to meet inflation expectations, rather than remaining relatively low until inflation subsides back to a similar level, could prompt the worst-case scenario of an inflationary feedback loop.

ANZ research adds the negative productivity shock of COVID-19 means firms are receiving less output per worker despite paying higher wages. “This ‘wage-price spiral’ is just getting going – but should it gain momentum, subduing the wide-awake inflation dragon without causing a hard landing along the way will become a very challenging prospect.”

In February, ANZ analysts published their forecast for further tightening in the labour market over early 2022, to 2.9 per cent unemployment before a gradual rise to 3 per cent in 2023 as higher interest rates take effect. This research anticipates private-sector wage growth will accelerate to a peak of 3.8 per cent in late 2022 from 2.8 per cent YOY in 2021.

The arrival of the Omicron COVID-19 variant is a complicating factor. It was only confirmed to have begun circulating in New Zealand in mid-to-late January 2022, after the country enjoyed an existence largely free of the virus and related restrictions for much of the past two years.

ANZ research published in February this year says the impact of 2021’s Delta outbreak was more persistent than indicators from the back end of the year suggested. Underemployment rose to 3.4 per cent from 3.2 per cent while average hours worked were down 4.1 per cent. It adds: “With the Omicron variant now dominant in New Zealand, it is likely we will see further volatility in measures of labour [usage], as worker absenteeism has been very high overseas during the latest Omicron wave.”

This could pose a risk to New Zealand’s participation rate, which has buoyed employment figures and in turn inflation. While other countries have seen participation rates drop off throughout the pandemic, the rate in New Zealand has increased. Q4 2021 recorded a participation rate of 71.1 per cent, down 0.1 per cent from its all-time high in the previous quarter.

ANZ research says there could be a significant drop in participation if the overseas experience of widespread community spread caused by Omicron occurs in New Zealand. “That would only exacerbate the mismatch between labour demand and supply – and therefore boost inflation. At this point, it’s actually an upside risk to already too-strong domestic inflation.”

HIGH-GRADE ISSUERS YEARBOOK 2023

The ultimate guide to Australian and New Zealand government-sector borrowers.

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.