Demand drivers rebalance Australian bank issuance to fixed-rate format

The fixed-rate component of major bank deals in Australia has been notably higher in 2022. Market participants highlight various possible causes, though the most influential may be the pricing in of a more aggressive rate hiking curve than credit investors believe the central bank will deliver.

Kathryn Lee Staff Writer KANGANEWS

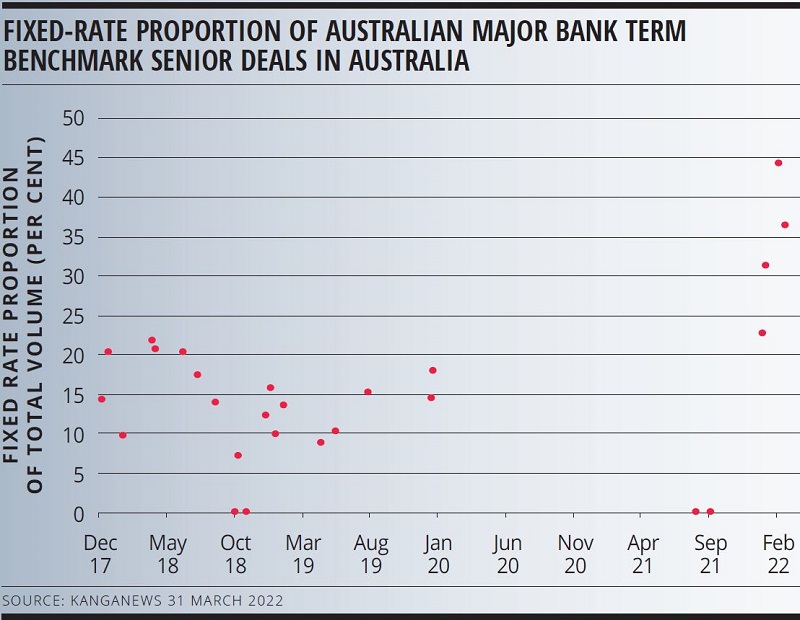

Historically, by far the biggest component of the volume of major bank domestic trades came to market in floating-rate note (FRN) format. However, fixed-rate tranches have taken a larger proportion of deals since the beginning of 2022 (see chart).

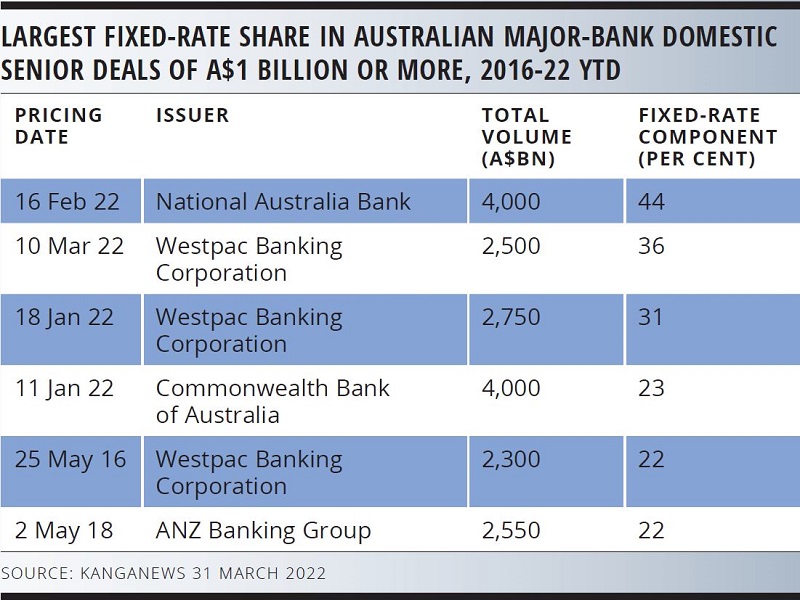

After returning to market in late 2021 with a brace of FRN-only domestic deals, the majors have found an unprecedented level of domestic fixed-rate demand in 2022. A greater proportion of each of the four major-bank domestic benchmark transactions priced in 2022 is in fixed-rate format than any other single deal going back at least as far as 2016 (see table).

Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA)’s A$1.1 billion dual-tranche tier-two print on 6 April also had a sizeable fixed-rate proportion, equating to 36 per cent of the final book. Fixed-rate tranches have been rare in the tier-two space. The last major to use the format in the domestic market was National Australia Bank in November 2019 – and even then the fixed-rate tranche only made up 16 per cent of the final volume.

There is general consensus that wider spreads and higher yield made bank issuance early in the year more attractive to credit funds, which are typically fixed-rate buyers by preference. For instance, Kapstream Capital confirms to KangaNews it recommenced buying bank paper in Q1 2022 after central bank support during the COVID-19 crisis made bank spreads too tight to offer value. Likewise, UBS Asset Management says widening spreads this year have made bank paper more attractive than it has been previously.

What is less clear is whether other factors are supporting such a significant fixed-rate component in bank deals. Bank funders themselves point out that their new-issuance spreads, while wider than the term-funding facility fuelled tights of 2020-21, have only swung back into historical range – they have not blown out to a new wide level. In isolation this might be expected to bring fixed-rate investors back into bank books but not to push this component to an unprecedented level.

Some observers continue to believe the phasing out of the committed liquidity facility (CLF) is playing a role. Banks that previously bought substantial quantities of their peers’ paper to hold as regulatory liquid assets will no longer be able to do so as the CLF heads toward zero. Notably, bank books are typically FRN buyers. Identifying the rise of bank fixed-rate issuance in a February research note, Tally Dewan, financials and securitisation strategist at CBA in Sydney, hypothesised that “it could be a reflection of phasing out of the CLF and associated likely reduced demand from the balance sheets”.

Dewan tells KangaNews this is a logical conclusion from the information at hand. “It is a natural progression. The CLF is going and if this means real-money managers buy more of deals, there is likely to be a greater skew toward fixed-rate notes,” she explains. “We do not think balance sheet participation from the major banks will go to zero as major bank issuance is still a repo-eligible product. But it will be smaller.”

On the other hand, bank issuers themselves have consistently downplayed the significance of the liquidity book bid and insisted the end of the CLF should not be material to their funding profile. For instance, speaking at a KangaNews-RBC Capital Markets roundtable in late 2021, Mostyn Kau, Melbourne-based head of group funding at ANZ, said: “A lot has been made of the balance-sheet bid in domestic term issuance. My view is there may be a slightly reduced bid around the edges but… this bid is not something we have relied on or targeted. We always prioritise real-money investors, as I am sure all the banks do. More is made of it than is perhaps warranted.”

The shape of benchmark deals priced in 2022 does not seem to have altered this view. “The fixed-rate bid is all about what real yields are doing,” says Lucy Carroll, director, global funding at Westpac Banking Corporation in Sydney. “It is clear from the tranching that the FRNs are not inherently smaller, it is that the fixed-rate notes are larger.”

DEMAND DRIVERS

In fact, the changing composition of bank deals may be driven primarily by domestic fund managers’ view on relative value. Pauline Chrystal, portfolio manager at Kapstream in Sydney, tells KangaNews: “With spreads widening and a lack of corporate issuance, bank paper has been looking more attractive – including on a relative basis. Corporate issuance traditionally carries a premium over banks because it had less liquidity. But this premium has reduced a lot: it is currently around 6 basis points having been 12 in 2020. Banks are more attractive to us so we have started dipping our toes back in.”

Tim van Klaveren, Sydney-based managing director and head of fixed income at UBS Asset Management, takes a similar view on improving relative value, but adds the addition of fixed-rate tranches was a significant factor in deciding to participate in early-year deals. “Going forward I expect bank balance sheets will still have interest but hopefully they will not be as dominant as in the past, which means real money will get a bit more say,” he adds.

Pricing factors also appear to be supporting a specific preference for fixed-rate paper over FRNs within real-money allocations. The market is pricing in an aggressive Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) hiking cycle, which makes fixed-rate securities particularly attractive to investors who believe the central bank will be more measured.

Dewan highlights this positioning in her research note, arguing it may reflect buy-side expectations that yield has risen too far. This would naturally prompt a preference for fixed-rate securities to lock in attractive pricing. While the domestic major-bank new-issuance market was silent from mid-March to at least early April, this would suggest some underlying support once near-term conditions ease.

“The reality is a lot of rate rises are factored into the curve,” says Phil Strano, senior portfolio manager at Yarra Capital Management in Melbourne. “We feel it is unlikely the RBA will raise to the extent priced into the market. The December bank bill contract is sitting close to 2 per cent, which is effectively factoring in 7.5 rate rises between now and the end of the year. I do not think our housing market could cope with this.”

This view drives security preference. Strano continues: “This means it is actually quite attractive to access fixed-rate rather than floating-rate securities right now, because with floating rate we are effectively only getting a margin over cash as opposed to all these factored-in interest-rate rises as we go up the curve.”

The fixed-rate bid is all about what real yields are doing. It is clear from the tranching that the FRNs are not inherently smaller, it is that the fixed-rate notes are larger.

SECONDARY FACTORS

There may be additional factors at play. Some market users suggest the way the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has begun to benchmark super funds might also drive fixed-rate demand. Under the new guidelines, super fund-owned Australian fixed income assets are benchmarked against the exclusively fixed-rate Ausbond Composite 0+ Index.

“It would make sense not to stray too far from the benchmark to avoid underperformance,” Chrystal comments.

Offshore demand does not appear to be a driver, even though distribution data show Asian buyers have been relatively active in bank deals in 2022. These accounts appear more inclined to support FRN tranches.

For instance, Asian investors took just one-quarter of the A$1.25 billion five-year fixed-rate tranche of NAB’s February benchmark, compared with 55 per cent of the A$1.4 billion five-year FRN. Nearly half of Westpac’s A$1.9 billion five-year FRN priced in January sold into Asia, compared with just 27 per cent of the A$850 million fixed-rate tranche.

Whatever the precise weighting of factors supporting the uptick in the fixed-rate component of bank deals, market users believe the changed conditions experienced during March will likely not have affected underlying demand characteristics. There has been a temporary pause in senior bank issuance since Westpac’s deal on 10 March, but CBA’s tier-two suggests the same drivers are still in play.

Chrystal tells KangaNews: “None of the parameters that made fixed more attractive than floating have materially changed, so I do not expect a shift in preference.”

- The original version of this story transposed geographical distribution data for the NAB February deal. This has been corrected.