Credibility key to carbon trading boom

Market users say corporate engagement with Australia’s carbon market continues to grow despite recent headlines questioning the integrity of the instruments. The negative coverage demonstrates why credibility is critical as this voluntary market takes its place supporting corporate net-zero goals.

Chris Rich Staff Writer KANGANEWS

Australian carbon offsets came under the spotlight in 2021 after corporates and speculative investors drove the spot price of Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs) to skyrocket. ACCUs are generated by greenhouse gas (GHG) abatement activities (see ACCUs 101 box), and can be bought and then cancelled by other entities to offset an equivalent volume of their emissions.

ACCUs 101

Set up by the federal government in 2012, the Clean Energy Regulator (CER) issues Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs) on behalf of the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF).

It also registers projects, runs auctions and manages carbon-abatement contracts. Each Australian carbon credit unit (ACCU) represents one tonne of carbon dioxide or equivalent avoided or removed. There are 38 approved methodologies for ACCU generation.

ERF projects generally take 1-2 years from when they are registered before they are issued their first ACCUs. Once registered, projects can generate ACCUs for 7-25 years, depending on the method.

Since 2013, more than 106 million ACCUs have been generated. The CER is the largest buyer of ACCUs, purchasing them in the primary market from project proponents via carbon abatement contracts in a reverse auction, semi-annually. In Q4 2021, 88 per cent of ACCU demand came from the ERF.

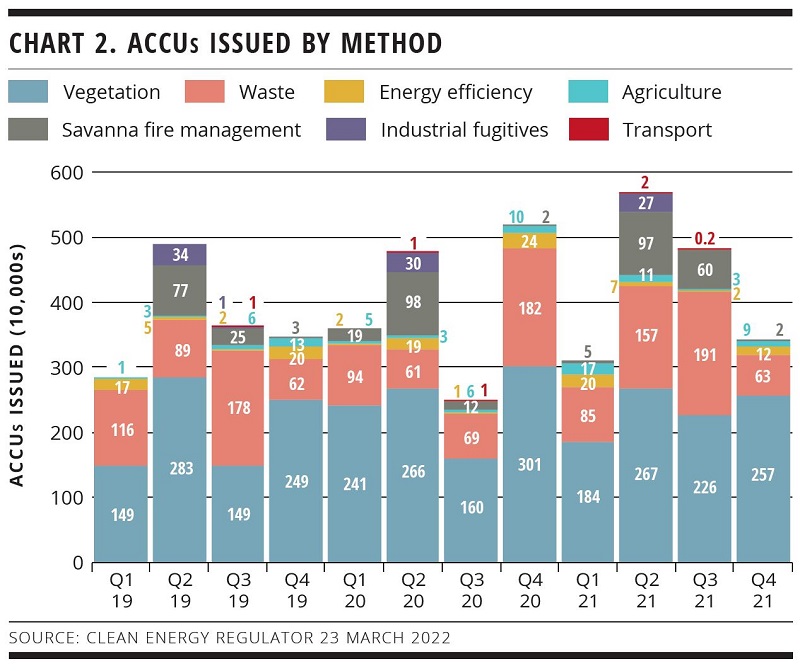

The CER issued 17 million ACCUs in 2021, an increase of 1 million from 2020, while total holdings in Australian National Registry of Emissions Units accounts increased by 47 per cent to 11.5 million units by year end.

A key difference in Australia is that carbon offsets are not part of a legislated carbon pricing system. The only element of compulsion is the narrow safeguard mechanism. This was established as part of the ERF in July 2016 to send a signal to companies to avoid increasing emissions beyond business-as-usual levels.

It attempts to achieve this by placing a legislated obligation on Australia’s largest greenhouse gas producers to keep emissions below a baseline, compelling them to purchase ACCUs if they exceed it. This obligation applies only to businesses that emit more than 100,000 tonnes of “direct” CO2 equivalent per year. Those covered span a range of industry sectors including electricity generation, mining, oil and gas extraction, manufacturing, transport and waste.

But it applies to barely 200 companies. This has led market users to question the effectiveness of the safeguard mechanism’s stated ambition and indeed the purpose of the mechanism.

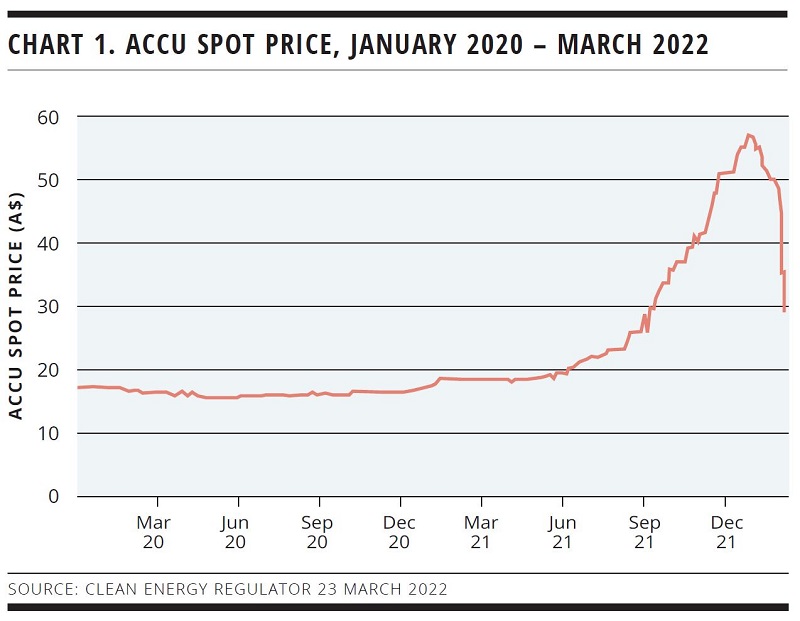

Rising interest in the asset class drove the ACCU spot price to a peak of just more than A$55 (US$41) in early 2022, having traded at less than A$20 prior to July 2021 (see chart 1). The price dipped below A$50 in late February and crashed in early March following government intervention (see Tinkering Taylor box).

The price action has brought the Australian carbon trading market under the spotlight, including suggestions of companies using non-ACCU securities to greenwash emissions and sidestep the implementation of credible transition plans. Questions have also been raised about the quality of emissions reduction schemes that generate new ACCUs.

Market users say growth in use of carbon offsets is, overall, a positive development but maintaining credibility across the system and awareness of its inevitable constraints is vital.

Australian carbon trading has been waiting for a spark for some time. Brad Kerin, Melbourne-based general manager and company secretary at the Carbon Market Institute (CMI) – an independent industry association – says the explosion of demand last year had its initial catalyst in the market signal sent by the Paris Agreement in 2015.

Right now, as the urgency to act increases Kerin says institutional investors and banks are moving beyond asking companies how they are reporting climate risk. The focus is now on near-term demands for climate-risk management plans.

The increase in spot price of Australia’s carbon offsets is not unique. In 2021, according to the Clean Energy Regulator (CER), EU Allowance pricing rose by 125 per cent to end the year at nearly €75 (US$83). But the drivers are not identical. A large component of delayed interest in ACCUs can also be accounted for by the long, politicised history of Australia’s attempt to establish an emissions-trading scheme – in particular the narrow nature of the compulsory usage scheme, the “safeguard mechanism”.

Kerin says: “The volume of ACCUs surrendered under the safeguard mechanism is relatively small, especially compared with the millions of tonnes of emissions created by the affected organisations and with increasing voluntary actions.”

In fact, with no cap and trade setup in place, Australian carbon units were at best a marginal proposition for close to a decade. Rob Fowler worked on the initial scheme and is now a Melbourne-based partner working in energy transition at global management consulting firm, Partners in Performance. He tells KangaNews Sustainable Finance the end of the carbon pricing scheme left offset credits in something of a limbo.

“When [former prime minister Tony] Abbott dispensed with the carbon price in 2014, he put the offset side on life support,” Fowler explains. “The system has supported users to keep generating projects with the government guaranteeing it will buy the credits generated, but the price has been minimised as a result. It sat around A$13-15 dollars for most of the rest of the decade.”

By establishing fixed-delivery contracts that could not be broken, Fowler says the government locked up significant supply of offset credits that is not available to any prospective buyer in the secondary market other than the government. “It has been a real constraint on supply, so when a bit of demand came along last year the spot market could not support it.”

Market users confirm the ACCU spot market is highly illiquid and opaque. Sources tell KangaNews Sustainable Finance only small transactions from a handful of brokers get published, with the data likely not painting a true picture of demand and supply dynamics, or of price.

Tinkering Taylor

Australia’s federal government has changed the rules for fixed-delivery carbon offset contracts to allow project proponents to take advantage of higher private market prices. Market response to the decision is mixed as it is not clear who ultimately benefits and there is concern about the consequences of constant government intervention.

The federal government announced changes to Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) contracts on 4 March. Under the new arrangement, project proponents will be able to break fixed delivery contracts – on payment of an exit fee to the Commonwealth – and sell their Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs) in the private market.

Angus Taylor, minister for industry, energy and emissions reduction, said when announcing the changes that the average fixed-delivery price was around A$12 (US$9) per ACCU compared around A$50 in the private market. The ACCU spot price crashed to A$30 after the announcement. “These reforms will lead to more ACCUs becoming available to the market in an orderly and transparent way, which will help meet the increasing voluntary demand for domestic offsets,” Taylor insisted.

The Clean Energy Regulator (CER) introduced optional delivery contracts in March 2020. Prior to this, project proponents could only enter into fixed-delivery contracts with the Commonwealth. Optional-delivery contracts were quickly embraced to underwrite and de-risk projects while supplying ACCUs to meet secondary market needs.

VOLUNTARY DEMAND

Few – if any – expected ACCU prices to push past A$55 after such a long period of near stagnation. However, the consensus of projections late last year did anticipate prices climbing to A$40, albeit only by 2030.

Expectations of higher ACCU prices are based on the idea that corporate user demand will continue to grow even in the absence of legislative compulsion. Carbon offsets are increasingly becoming a tool for businesses to mitigate emissions in the short and medium term while they transition to net-zero emissions or await cost effective technology to reduce emissions profiles on a more permanent basis.

In effect, as the number of companies that take their own transition seriously increases so does demand for a product that can offset emissions while businesses go through the process of reducing their own carbon intensity.

Though compliance with the safeguard mechanism continues to contribute a portion of demand for ACCUs, market users say the majority is now coming from corporate users that want to offset emissions on a voluntary basis.

The safeguard mechanism saw just more than 400,000 ACCUs surrendered to the CER in the 2020/21 reporting year. Voluntary cancellation recorded by Climate Active – the government-branded certifier of Australian businesses seeking to achieve net-zero carbon emissions – surpassed 600,000 ACCUs, a 40 per cent increase on 2021.

According to the CER, 195 entities cancelled ACCUs in 2021, compared with 123 in 2020. The regulator says the finance sector was particularly active, accounting for 70 per cent of cancelled volume in Q4 2021. Financial institutions have been offsetting organisational emissions as well as introducing products and services targeted at the carbon market. These include carbon offsetting, climate-targeted managed funds and carbon offset based financial derivative instruments.

Alex Toone, executive general manager, commodities, trade and carbon at Commonwealth Bank of Australia in Sydney, says there is no turning back even on behaviour that is, in a legal sense, voluntary. “The level of understanding of ACCUs has accelerated quite significantly in client conversations over the last 12-18 months,” he says. “Most clients are already somewhere on the path to measuring, reducing and offsetting emissions, and offset is typically part of the solution to meet voluntary commitments companies have made.”

OTHER OFFSETS

ACCUs are not the only option for companies seeking to buy carbon offsets in the voluntary market. There is a range of other international offsets, which users say vary in quality and price. Options viewed as high-quality include certified emission reduction units (CERUs), verified carbon units (VCUs) and verified emissions reductions (VERs).

ACCUs are a small component of the market. The CER claims users surrendered12 million CERUs in 2020/21 – almost 20 times the ACCU volume. In 2020, voluntary demand for ACCUs accounted for 2 per cent of Australia’s carbon offset market and 8 per cent of all voluntary demand, with the overwhelming majority of voluntary participation using CERUs, VCUs and VERs – in roughly equal proportions.

Kerin says price explains why most users are plumping for international units. “If the price of ACCUs was lower I am sure there would be greater investment in Australian projects, particularly from domestic businesses,” he says. “Companies may purchase some Australian units, for reputational or internal policy reasons, but fill the rest of the portfolio with cheaper international units that still meet due diligence requirements.”

Recent changes to Climate Active certification should increase voluntary demand for ACCUs. In December 2021, Angus Taylor, Australia’s minister for industry, energy and emissions reduction, announced a requirement for nonenergy Climate Active certifications to use at least 20 per cent ACCUs in their carbon-offset portfolios. He also announced new forms of recognition for businesses that buy 100 per cent ACCUs or purchase 100 per cent renewable energy.

While supportive of Climate Active 100 per cent recognition, CMI is concerned with the plan to implement the 20 per cent requirement for Climate Active certification – in particular whether supply can be brought online to meet greatly expanded need without strangling the market through cost.

Most companies are serious about their commitment to emissions transition. But if sufficient ACCUs cannot be generated to meet their need the whole system cannot survive in a cost-effective form.

“There has been no modelling produced on what the impact may be on existing supply and prices, nor what the quantum of abatement may be required for these new certifications – and therefore the impact this requirement may have on an already illiquid market,” Kerin says.

He continues: “There was very limited consultation on this plan and CMI is concerned unintended consequences could include pushing companies away from Climate Active into alternative carbon-neutral certification schemes. ACCU restrictions or quotas could negatively affect future export potential and broader participation in international markets.”

FUTURE DEMAND AND SUPPLY

The voluntary nature of Australia’s carbon market means it is difficult to gauge the likely scale of demand and thus whether it is possible to generate sufficient supply of local offset units to meet it.

Toone notes the challenge of generating new supply in carbon markets, which takes much longer to bring online than it does for other commodities. “If there is suddenly a whole new group of corporates that want to offset, there will not be enough available supply to meet the demand.”

Voluntary markets rely on companies’ judgements about how many offsets they will purchase – if they decide to purchase them – and to make these projections public, Kerin explains. But he says the Australian market is not sufficiently transparent at this stage to send reliable price signals. In particular, most carbon-offset transactions in Australia are completed on an OTC basis with no established reporting system.

Fowler says it can also be difficult to gain an understanding of the supply pipeline due to new projects and methodologies coming online and reshaping the outlook with little warning. “There is all sorts of uncertainty in the market, which has been one of the great challenges. It is driven by policy far more than the practicality of on-the-ground activity,” he says.

There are plans to improve transparency and market functionality, however. The government-led Australian Carbon Exchange – which will trade ACCUs and potentially other types of carbon units and certificates – is expected to launch in 2023.

But a heightened focus on ACCUs will only make the supply issue more challenging. Some companies are trying to be proactive on this issue by entering long-term off-take agreements to secure future ACCU supply outside the secondary market, as well as to improve oversight.

Property firm ISPT has done just this. It partnered with Landcare Australia on a 25-year carbon-conservation land bank, having purchased ACCUs in the secondary market for the second year in a row in 2021 to achieve carbon neutrality across its owned and operated properties.

ISPT surrendered 97,000 ACCUs in December, via CBA. The volume represents more than 10 per cent of voluntary private and state and territory demand for ACCUs during 2021.

ISPT aims to be carbon positive by 2025 and from there to sell surplus offsets to its investors and customers. According to Alicia Maynard, ISPT’s Sydney-based general manager, sustainability and technical services, the company’s investors – which include some of Australia’s largest industry superannuation funds – expect immediate and direct action on climate change.

“We mapped the process to reduce our emissions, including the role offsets would play in our carbon-neutral pathway,” she says. “A self-generation model will give us the opportunity to protect our own interests and investment with annual audit regimes and ensure we do not overestimate ACCU yield.”

Carbon offsets are a key component of treasury discussions, says Simon Milne, treasurer at ISPT in Melbourne. The company had to ensure its treasury policy allowed it to trade ACCUs and that it was able to assess mark-to-market movements, which flow through to the balance sheet.

In any case, the CER expects higher spot prices will encourage more project registrations, including from large demand-side players contracting directly for the ACCU supply they need.

To some extent, higher demand should prompt more supply – albeit likely with a lag effect. James Schultz, chief executive at GreenCollar in Sydney, tells KangaNews Sustainable Finance a higher ACCU price should open up opportunities to develop projects in the land-based sector – to date, the largest generator of ACCUs.

The question is where the natural cap on supply will be found. But market users agree it will be reached long before all hypothetical demand for offset units comes to the market. “The supply of carbon abatement and emissions reduction opportunities in the land sector is not infinite,” Schultz cautions. “We will hit a point where it will become more challenging to create new or additional abatement.”

GreenCollar says it is Australia’s largest environmental markets investor and project developer. It works with farmers, graziers, traditional owners and other land managers to identify and create commercial opportunities through nature-based projects. Its portfolio consists of more than 200 registered and contracted projects covering more than 10 million hectares, generating more than 126 million ACCUs.

Vegetation, waste and savanna fire management are the three main methods for ACCU generation (see chart 2). Vegetation projects generate abatement by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it as carbon in plants as they grow, with activities including reforestation, revegetation and protecting native forest or vegetation that is at imminent risk of clearing.

“It is not a short-term issue,” Schultz says. “It means we need to look beyond traditional land-based carbon projects, such as human-induced regeneration and avoided clearing.”

The positive news is that the ability to deliver low-cost, large-scale carbon projects in the land sector – such as avoided deforestation and human-induced regeneration – has been established. Kerin believes higher ACCU prices may make other project and method types more economically viable.

METHOD PREFERENCE

As projects that generate ACCUs proliferate, the need to ensure emissions abatement is fit for purpose and above board will also increase. Corporate ACCU users typically perform their own due diligence on the source of their credits. Market users say this often goes beyond the CER verification that comes with ACCU issuance.

Kerin explains, though, that corporates have differing levels of understanding about what the due diligence process should look like and there are natural challenges in what remains a nuanced and technical process. High-emitting corporates often have internal carbon trading teams in place, but most others turn to third-party service providers. “It then becomes a question of what standard of due diligence these advisers are performing and thus what types of units they are recommending,” Kerin says.

Part of the challenge is that ACCUs are not created equal, at least in the sense that they derive from a range of emissions-offset projects. Some corporate ACCU buyers prefer units that derive from specific methodologies and are keen to avoid others that they do not consider to be additional. Additionality, in this context, means whether a project or activity creates emissions reduction that would not have occurred in the absence of an incentive.

But there have long been questions about additionality and baselines – where offsets are measured and projects receive credit for an activity that has not yet occurred and may never do so. “If there is an intervention to not do something – like avoided deforestation or land clearing – it is very difficult to judge whether it is legitimate,” Kerin explains.

The main problem with land-clearing methodologies is that it can be difficult to assess whether a landholder with a permit to clear vegetation ever intended on using it. “Positive interventions – such as planting trees or savanna burning – are much easier to justify,” Fowler says.

Avoided deforestation and land clearing, as well as two other methodologies underpinning ACCUs, made headlines recently as a former chair of the emissions reduction assurance committee claimed widespread fraud (see Questionable methodology claims box). Procurement decisions ultimately come back to risk appetite and the standard of due diligence performed, Kerin says. “Risk thresholds may be too high for users to manage due to commentary about methods like avoided deforestation. But others may see the integrity of the unit and trust the institutions that provide the method.”

Questionable methodology claims

Market participants claim the integrity of Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs) remains high despite a series of potentially damaging exposés. In turn, the Carbon Market Institute (CMI) rejects allegations of fraud and highlights concerns with the assumptions that back them.

On 24 March, Andrew Macintosh, a professor at Australian National University and former chair of the emissions reduction assurance committee, published a research paper claiming Australia’s carbon market is a fraud.

He identified the three main types of projects – avoided deforestation, human-induced regeneration (HIR) and the combustion of methane from landfills – within the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) as lacking environmental integrity.

“The available data suggest 70-80 per cent of the ACCUs issued to these projects are devoid of integrity – they do not represent real and additional abatement,” Macintosh said. “All the major emission reduction methods have serious integrity issues, either in their design or the way they are being administered.”

Maynard reveals ISPT consulted advisers in the industry to set up a risk appetite framework for carbon offset procurement. Two governing principles emerged from the process. “Anything we do in the offset market has to be based in Australia and has to involve working with Australian communities on the land – preferably Indigenous community groups,” she explains.

Carbon abatement projects that achieve additional environmental, social and governance benefits are called co-benefits – and are highly sought after. Examples include increased biodiversity from the protection and regeneration of native vegetation and providing new income streams for Indigenous communities via use of traditional fire-management practices.

Toone says demand for ACCUs with co-benefits has risen significantly over the last 12 months. “Clients are very specific about exactly what type of credit they want to buy – whether it be from Indigenous groups, generated out of a particular state or from their own supply chain. We have been surprised at how specific client demand has been but expect the trend to continue.”

Australian-based offsets with co-benefits are in especially short supply, though. “Some of the respondents to our tender simply did not have the volume ISPT needed to cover its emissions,” Maynard reveals.