Dealers hit risk limits and secondary liquidity stalls as investors eye rising yield

Dealers across Australian dollar fixed-income markets neared or reached holding limits in Q2, further drying up liquidity that has been shallow all year. While trading volume is nearing financial crisis lows, market participants say clarity on rates and inflation could see a swift rebound – particularly in investment-grade credit – as investors hunt for bargains.

Daniel O'Leary Editor KANGANEWS

The US CPI print on 10 June, of 8.6 per cent – the fastest increase since 1981 – shocked the market, which expected inflation over May to be in line with 8.3 per cent for April and 8.5 per cent for March. The Australian dollar secondary market responded swiftly. Dealer balance sheets stopped buying and started offloading bonds, while outflows from fixed income, retail-focused funds and Asia-based private bank investors accelerated. The Australian dollar fixed-income market came to a near halt.

“It is a very simple situation – everyone was selling risk and nobody was buying it,” says Mark Bayley, portfolio manager at Kapstream Capital in Sydney. “Dealers only have finite risk appetite and limited balance sheets. Once these limits are reached, traders are less able to provide a bid.”

Kapstream manages several Australian credit-focused fixed-income funds, with A$14.4 billion (US$10 billion) in assets at March 2022. “Overall liquidity has been challenging and it seems more prolonged than the COVID-19 selloff,” Bayley adds, noting pockets of liquidity can still be found in very specific high-quality corporate bonds. “This has been going on for three or four months, partly due to the complete lack of investor appetite.”

Domestic dealer balance sheets were already constrained from Q1, when interest rates started to rise. Following the CPI print, the US Federal Reserve hiked its benchmark interest rate by 75 basis points – its most aggressive increase since 1994. Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) governor Philip Lowe has signalled the country’s cash rate will increase further, following 50-basis-point hikes in June and July.

Speaking on a trading and liquidity panel at the KangaNews Debt Capital Market Summit in Sydney on 23 May, Greg Kumar, director and head of Australian rates trading at RBC Capital Markets in Sydney, said the issue was partly structural in nature as modern trading desks already run much smaller positions that reflect the liquidity seen in the wider market.

“We have seen the electronification of trading and markets are re-pricing macro and geopolitical events in fractions of a second,” Kumar explained. “No human has the capacity or ability to reprice that fast. As electronification grows it is providing a lot of the market depth via programmes like CTAs [commodity trading advisers] or algorithms.”

Kumar said fixed-income markets had re-priced at unprecedented speed in 2022 as automated and electronic trading platforms exited trades. “Our positions are more cautious and based on client flows, because there is always a forthcoming event, such as a Fed meeting or employment numbers. There is always a reason for investors to sit close to the benchmark.”

Back-to-back events such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, supply chain disruptions affecting trade with China, rising inflation and the withdrawal of central bank QE have constrained global liquidity since February, leading dealers to revise risk limits for most of the year.

“Longer-dated and high-rated – triple-B-plus – credit is trading in the 200-basis-points-plus region, yielding more than 5 per cent – this is great value for regulated income streams and monopoly infrastructure assets. By our fair-value measure, credit is good value now. Will it get better? Possibly. But it can also turn around quite quickly.”

Button TextTHIS SELL-OFF IS DIFFERENT

Regulatory change in the wake of the financial crisis forced dealers to limit the amount of risk they can warehouse. This led many to shift to a more broker-focused business model, meaning that if flow is one-sided many dealers find it hard to provide liquidity.

However, during the COVID-19 sell-off dealers were bidding aggressively on bonds due to the lack of supply and the flush of liquidity circulating through the system. The withdrawal of central bank liquidity means this year’s sell-off is different, according to market participants.

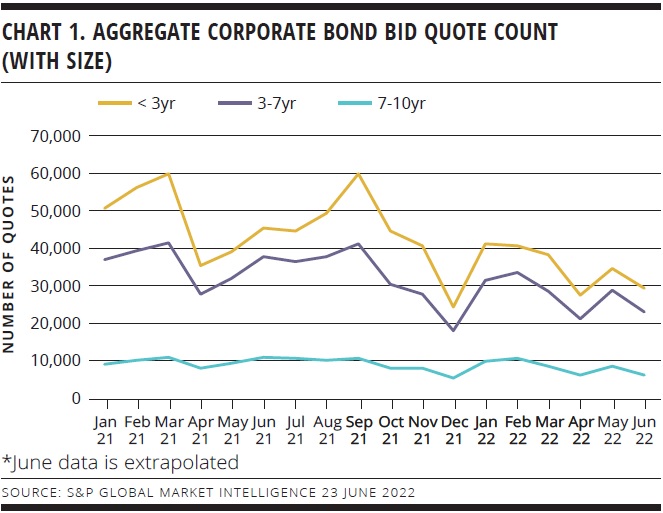

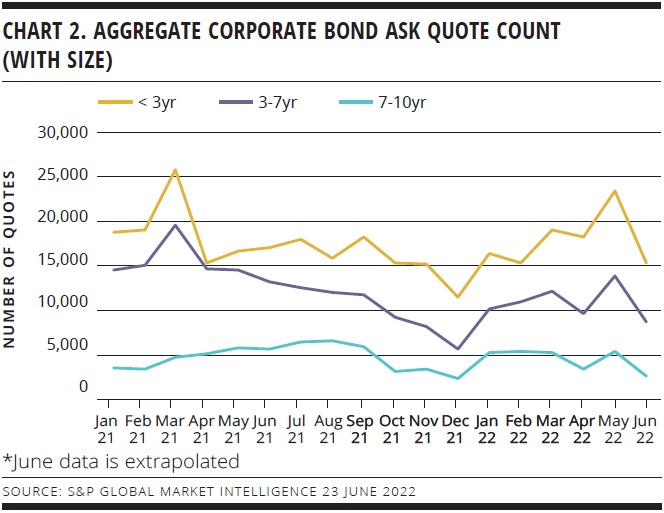

S&P Global Market Intelligence data show aggregate corporate bond bid quote counts with size have fallen since January (see chart 1). The trend accelerated in June. Meanwhile, offers steadily increased over the same period before collapsing in May and June (see chart 2).

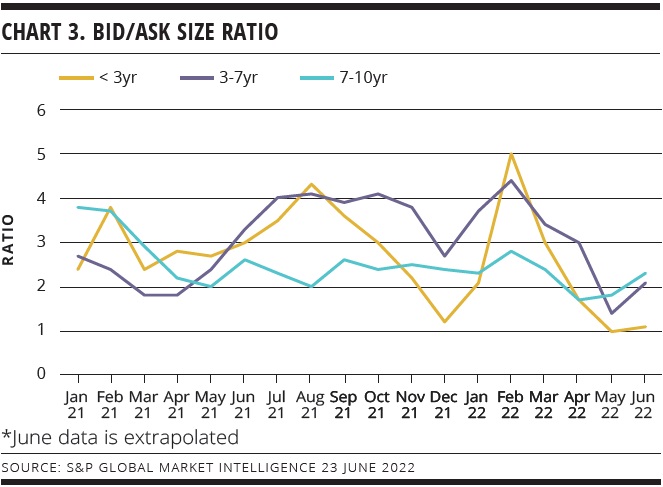

Chris Pashley, Sydney-based managing director at S&P Global Market Intelligence, says the data support the notion that dealers are looking for opportunities to downsize inventory levels where possible, noting recent dealer quote activity has been heavily offer-sided (see chart 3). He says dealers managing inventory would have found the recent widening in corporate bond spreads challenging.

Pashley adds that dealer de-risking activity is also evident in the comparative lift in shorter-credit-duration quote activity. “Liquidity providers are avoiding bid-side, longer-dated credit duration while still trying to support their clients the best they can.”

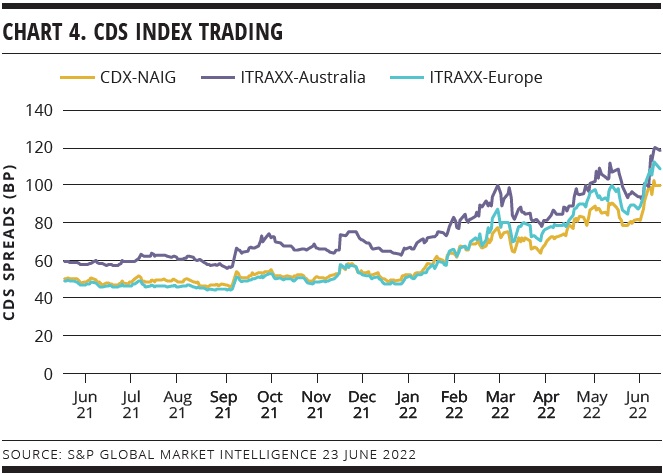

Australia does not have a liquid single-name credit default swap (CDS) market, which further complicates liquidity. Traders and credit investors typically trade the Australian or European ITRAXX indices, which provide imperfect hedges and introduces tracking error to portfolios. These indices rose sharply in June as market participants sought insurance (see chart 4).

“Australian corporate bonds are difficult to hedge,” Pashley confirms. “There is not an appropriate market in Australia that can manage directional risk from an interest-rate perspective, so large corporate bond inventory that has not moved during this sell-off will pose a risk.”

International investors retreat

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)’s yield curve control (YCC) policy dampened international investor appetite for Australian dollar fixed income by suppressing yield to an unprecedented degree. Market participants say a substantial international bid is unlikely to return to the secondary market any time soon.

The RBA’s YCC – introduced at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 – differed from other QE programmes as it attempted to supress long-term interest rates by setting a yield target on 10- year government bonds.

According to a Federal Reserve Bank of New York report published in April, YCC worked initially when the market expected short rates to stay at zero for longer. “But as the global recovery and inflation gained momentum in 2021, lift-off expectations moved up, the RBA purchased most of the outstanding amount of the targeted government bond and its yield dislocated from other financial market instruments,” the authors of the report wrote.

“The Australian credit and rates markets are not the core competency of offshore portfolio managers – they can be seen almost as an emerging market by some European and North American fund managers that might play in them when there is strong value. But when volatility is high, they are very much focused on their local markets.”

Helen Mason, fixed income fund manager and senior credit analyst at Schroder Investment Management Australia in Sydney, says dealer balance sheets typically have holding periods of three months before they are required to turn their books over.

“This causes massive issues for dealers when they have to sell the credit,” Mason explains. “They can provide a good level to buyers, but it also means they cannot take any more risk on their books. If they are going to trade with us, it is going to be significantly wider.”

Bayley says selling corporate bonds has been tough outside specific names, with longer-dated paper generally even more challenging. “The dealers have certain limits for these bonds,” he notes. “Outside this, dealers are doing their best to provide bids, but they are passing more frequently.” He adds that fund managers are typically holding high cash balances, however – so high yield will eventually tempt many back to the market.

YIELD RETURNS

Before the 10 June CPI print stalled the secondary market, outright fixed-income yields were tempting investors.

In late June, the 10-year Australian government bond yield was more than 4 per cent, 2.4 percentage points higher than the same time last year. US Treasuries yielded 3.3 per cent for 10-year tenor, up 1.8 per cent. Yields on corporate bonds have kept pace. For instance, Ausgrid Finance’s triple-B rated 2026 transaction yielded about 5.9 per cent in mid-June, up from 2.8 per cent in January, while Lendlease’s triple-B rated 2027 transaction yielded 6.1 per cent, up from 3.3 per cent.

Will Manfield, executive director and head of credit trading at Westpac Institutional Bank in Sydney, says the market has experienced some of its most constructive price action this year despite the negative spread performance. “Investors were looking at the all-in yield story and wanting to add credit risk,” he tells KangaNews.

Despite the illiquidity, Manfield says investors are still hunting investment-grade corporate bonds with a 6 per cent yield. “Australian dollar swap spreads moved 20 basis points wider in a week, so clearly the plumbing of the Australian fixed-income market is not healthy,” Manfield says. “But investment flows are coming back into credit.”

According to Manfield, Australian investors have so far managed the challenges posed by rising inflation and the central bank response quite well. “They came into 2022 with high cash levels and are well positioned to navigate further volatility,” he explains. “Overall, the tone is still very soft in investment-grade credit but Australian dollar is outperforming offshore markets as a result of limited corporate issuance.”

Mason says secondary trading can reopen as fast as it closed if conditions improve. “Longer-dated and high-rated – triple-B-plus – credit is trading in the 200-basis-points-plus region, yielding more than 5 per cent – this is great value for regulated income streams and monopoly infrastructure assets,” she adds. “By our fair-value measure, credit is good value now. Will it get better? Possibly. But it can also turn around quite quickly.”

“Right now, we have thin volume but continuous price discovery in vanilla instruments, so liquidity is reasonable. There is a different price for liquidity from what we have seen over the past 15 years, and this will take some time to get used to.”

Button TextSECONDARY PERFORMANCE

The performance of new bond issuance on the secondary market has been a sticking point for investors. Primary markets across fixed income sectors were active at the start of the year, particularly among financials that tapped senior-unsecured markets for the first time since the introduction of the term-funding facility. However, spreads have not held up against rising interest rate volatility.

Richard Garland, head of short duration credit and inflation at QIC in Brisbane, says primary issuance was well-received but participation and liquidity has not filtered through to the secondary market. “The market is very focused on rates volatility and at the same time concerned about a policy mistake leading to recession. This has led credit spreads to suffer,” Garland notes.

He continues: “Some normality was returning to credit markets, with primary issuance providing a guide to where spreads should trade. However, the US CPI print for May had investors questioning the idea of peak inflation, which in turn saw rates volatility increase again. High inflation and rates volatility is a toxic mix for credit spreads.”

Primary market flow across fixed income has declined steadily throughout 2022. Major banks were active at the start of the year, but their transactions also served to mark secondary spreads wider.

Market participants say the 5 basis point underperformance of Macquarie Bank’s A$350 million floating rate tier-two note – which printed in mid-June at 270 basis points over swap – compared with the bank’s A$500 million fixed-rate tranche illustrates an interesting dynamic playing out secondaries.

Manfield says fixed rate is outperforming floating-rate notes (FRNs) as investors hunt for attractive yield. “Offshore buyers – such as sovereign wealth funds – that have not been active in Australian dollar credit for a number of years are starting to dip their toes back into our market, specifically buying fixed-rate bonds. This is pushing those notes to trade well inside FRNs.”

It was rates volatility that drove the upward move in the Macquarie tier-two deal’s fixed-tranche yield curve, Manfield says.“The yield is attractive, especially to retail-focused funds. This does not make a lot of sense in a market that can asset swap – in theory investors could buy an FRN and swap it to fixed, so this is certainly an interesting theme.”

David Gallagher, Sydney-based managing director at Artesian Capital Management, says buying opportunities exist, with several single-A and triple-B corporate bonds yielding more than 6 per cent. “We have not had these yields for a decade,” he notes.

The running yield on Artesian’s corporate bond fund was 4.5 per cent in mid-June, higher than the 4.1 per cent average dividend yield of listed Australian companies. “Fixed income looks more attractive as an asset class than it has for the past 3-4 years,” Gallagher says.

READY FOR ACTION

Despite the illiquidity, investors are ready to deploy capital once markets settle, with many eyeing shorter duration, investment-grade credit, particularly at the triple-B level. However, greater transparency from central banks and an easing of inflation is needed, they say.

Mason says the fund she oversees has trimmed credit spread duration for the past couple of months and bought shorter-dated, high-quality corporate bonds with lower volatility. “We think this is ending and credit is looking better value,” she comments. “We are not at fire-sale levels yet, but we do not want to be selling credit from here. Corporate fundamentals in Australia are still very strong.”

Bayley agrees, noting Australian investment-grade default rates are very low. “Investors will realise Australian credit is incredibly attractive once rates calm,” he says.

This is even against the backdrop of an expected deterioration of global credit fundamentals driven by the possibility of a recession in the US. “There could be some spread decompression in lower-rated bonds, but investment-grade should hold its value better,” Bayley concludes.

As central banks attempt to tame inflation, concerns have shifted to recession. The Westpac-Melbourne Institute consumer sentiment index fell 4.5 points in June, reaching 86.4 – near levels seen during the financial crisis and at the height of the pandemic.

Garland says the breakeven level for ANZ’s A$4 billion multitranche May transaction, which priced at 4.1 per cent yield for the three-year maturity, was attractive. For an investor to have a negative mark-to-market outcome over the next year, all-in yield on two-year Australian major banks would need to be 5.5 per cent, Garland notes.

“While not impossible, a world where two-year Australian major-bank paper is yielding 5.5 per cent is difficult to imagine. If the RBA follows through with the aggressive market pricing, the probability of a recession will increase, therefore the interest-rate component of all-in yield will perform. On the other hand, if central banks can orchestrate a soft landing, credit spreads should crunch in. There are opportunities here: coupons are increasing and the forward looking carry environment is quite attractive.”

Pashley says Australian fixed income trading is not broken. “This feels more than a credit hiccup but it is not just a COVID-19-type shock to the system,” he says. “It is structural, as the market adjusts to inflation and QE withdrawal. But the implied default probabilities – not just locally – are still quite low.”

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.