New challenges, same securitisation story

The Australian nonbank securitisation market has been a story of almost unimpeded progress for the past decade or more. It is facing new challenges in 2022 and its resilience is being tested in more ways than one. But market participants retain confidence in the nonbank sector’s overall health and the value proposition of its core funding instrument.

Jeremy Chunn Editorial Consultant KANGANEWS

Laurence Davison Head of Content KANGANEWS

It has been a jarring 12 months for Australia’s nonbank financial institutions. They have seen their funding costs rise as borrowers digest a smorgasbord of rate rises, cost of living pressures, the end of pandemic-era support and falling house prices. The combined impact is leading to concern – for the first time in many years – that an as yet unknown, but significant, portion of Australian borrowers will struggle to keep up with mortgage payments.

The inputs to the household credit market have mainly – though, importantly, far from exclusively – turned negative at pace in 2022. Most significantly, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has begun aggressively hiking the cash rate and retail lending rates have followed more or less in lockstep.

Having bottomed out at 0.1 per cent in November 2020 – and not having been higher than 1 per cent since mid-2019 – the first small hike in May 2022 was the prelude to successive 50 basis point increases in June, July, August and September. While still not high on a historical basis, the pace at which the cash rate has increased is almost unprecedented. The last time Australian rates increased by 2.25 per cent, it took from June 2002 to March 2008. Local borrowers have had just four months to adapt to the most recent leap.

And adapt they must, because the Australian mortgage market provides little shelter from rising rates. While a swathe of borrowers fixed their home loan rate when offered ultra-cheap debt during the pandemic – rates supported by the RBA’s term funding facility, which offered banks three-year funding at a fixed 0.1 per cent – the market has historically been overwhelmingly variable rate. Many of the fixed terms were only for a year or two, which means that with every passing week more borrowers lose the comfort of locked-in, low payments and have to confront the increasing cost of variable-rate debt.

So far, arrears have held up well – though the lagging nature of the data means it may be too early to draw many conclusions. S&P Global Ratings published arrears data for the Australian housing market to the end of May 2022 on 17 August, with the data showing arrears at a post-financial-crisis low point for prime and nonconforming loans. Prime loan arrears of 30 days or more stood at 0.65 per cent, down by 0.3 per cent year-on-year. Nonconforming arrears were 2.24 per cent, down by 0.87 per cent.

Fitch Ratings data for Q2, published on 5 September, maintained the trend. Fitch’s Dinkum Index of 30 day-plus mortgage arrears in residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) structures rated by the agency stood at 0.82 per cent at the end of June, down by 0.32 per cent year-on-year and also a record low for the index.

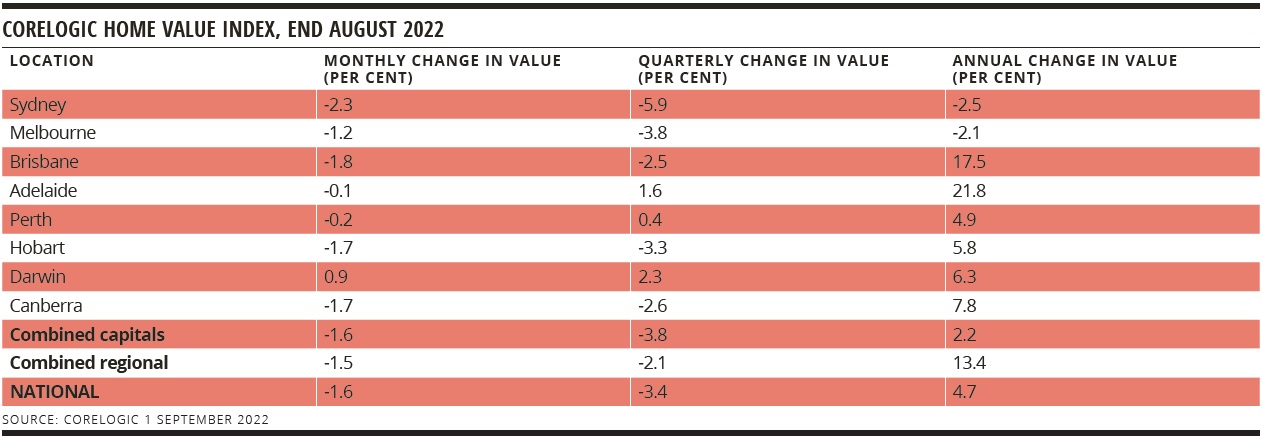

On the other hand, higher lending rates have started to bite in the housing market. CoreLogic’s Australian Home Value Index recorded its fourth consecutive monthly decline in August, the data also showing an accelerating decline and one that is becoming more broad-based geographically (see table). While the Sydney market continues to lead the way, only Darwin of Australia’s state and territory capitals did not record a property price fall in August.

It should be noted that house prices are falling from a high peak. The CoreLogic data show the declining trend in Brisbane and Adelaide is sufficiently recent that house prices are still showing growth in the high teens per cent or more for the past year. Sydney house prices, meanwhile, more than doubled in the decade to the end of 2021.

PACE OF CHANGE

This will be of scant comfort to mortgage holders who got into the market at or close to the house price peak and with borrowing rates at an all-time low. An era of cheap money saw many Australians chase the dreams they could catch. For a lot of them it was property.

It is undoubtedly the case that lending market conditions up to the early weeks of 2022 were primarily the product of an unusual combination of factors. The first was ultra-cheap credit, which had been available largely since the financial crisis but which was pushed to an unprecedented level by pandemic stimulus. On the other side of the coin, housing affordability was already at an all-time low as a result of the seemingly ever-upward path of house prices combined with stagnant wage growth.

The unwind of this complex latticework of factors, and in particular the pace of the unwind, leaves one group of borrowers especially exposed: those who entered the housing market during – or indeed because of – the bottoming out of lending rates but who had not had time to amass significant equity in their property before prices went into reverse.

Speaking at KangaNews and Natixis’s nonbank lender roundtable in Sydney in August, Martin Barry, chief financial officer at La Trobe Financial, emphasised that significant borrower pressure is yet to come through in most lenders’ books but also acknowledged: “First-home borrowers may be under pressure, specifically those with generally higher loan-to-value ratio loans originated in the second half of 2020 and 2021.”

Prime Capital’s chief executive, Paul Scanlon, added: “None of us were writing loans in 2020 or 2021 in the expectation that the conditions of the time would be with us forever. What is surprising, though, is the pace at which rate increases have come through.”

The settings for the next phase of the Australian household credit market now appear to be in place, at least in the sense that lending rates seem unlikely to fall significantly from their current level in the foreseeable future. But the jury is still out on how great the pain of higher rates will be and how far – if at all – it will spread beyond the most exposed cohort of borrowers.

In a 5 September research note, Gareth Aird, head of Australian economics at Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) in Sydney, explored the lagging impact of rate increases on borrower cash flow even in a largely variable-rate market.

He explained: “Interest accrues from a lender’s effective rate change date, which is typically roughly two weeks after the RBA increases the cash rate. This interest is added to a borrower’s outstanding debt. But, from a cash flow perspective, the impact is not felt for three months on average for a CBA customer. The lags across other lenders vary. But we estimate that on average the lag is around 2-3 months across the major lenders.”

On this basis, borrowers will start to feel the impact of the RBA’s first 50 basis point hike perhaps as late as mid-September. The September hike, even if it is the last of the 50 basis point increases for some time, may not hit the household balance sheet until close to Christmas.

“Interest accrues from a lender’s effective rate change date, which is typically roughly two weeks after the RBA increases the cash rate. This interest is added to a borrower’s outstanding debt. But from a cash flow perspective the impact is not felt for three months on average.”

Button TextSECURITISATION MARKET

These conditions have placed Australian securitisation market participants in a tricky position in 2022. On one hand, local nonbank lenders have ridden out challenges in the past. They came through COVID-19 not just largely unscathed from a credit perspective but also with record funding volume and a notable proliferation of active issuers. Even the global financial crisis did not defeat the sector.

In both cases, the Australian government was willing to provide direct and indirect support to nonbanks, even if the precise nature of what was offered was not as munificent as the backing provided to authorised deposit-taking institutions.

On the other hand, the miasma of uncertainty that has plagued most markets in 2022 has perhaps lain heaviest on securitisation, at least in Australia. The pace of rate increases and the lagging impact on household balance sheets means transactions had to be completed in an environment in which no-one could say with any degree of confidence just how much borrower stress will come through.

The size and breadth of the Australian nonbank sector means there has been little option but to keep issuing. Nonbanks report that warehouse liquidity has held up well in 2022 – there has been much less retreat of bank funding from the sector than was the case in the financial crisis – but there is also a widespread reluctance to rely too heavily on the type of short-tenor funding warehouses provide. Some nonbanks have established access to alternative funding avenues and others are actively exploring them. But the reality is that the sector still largely relies on access to the public securitisation market.

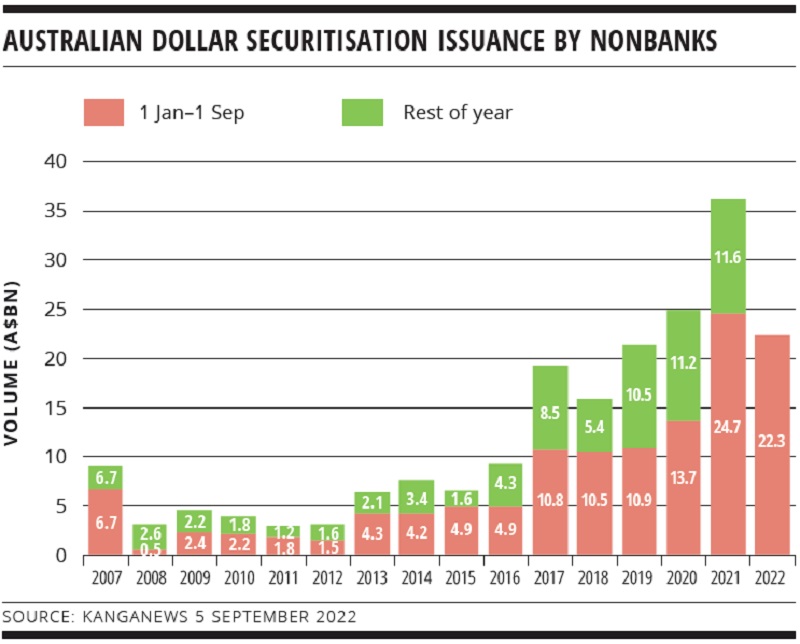

The good news is that even the uncertainty of 2022 has not closed off access to capital market funding. The A$22.3 billion (US$15.1 billion) of Australian dollar securitisation issuance by nonbanks in the first eight months-plus of the year almost matched the record pace from 2021 and comfortably exceeded the equivalent period of any previous year (see chart).

Clearly, liquidity has not evaporated completely. “Given we are in the midst of pandemic emergency monetary policy accommodation being quickly removed, the fact we have seen as much issued in the RMBS market in the first half of 2022 is actually quite notable,” comments Ken Hanton, director, client management and execution at National Australian Bank in Sydney. “Notwithstanding the challenges the market has faced and continues to face, it is not going to be as lean a year as some might have thought.”

While outright volume has held up well, this is not necessarily a sign of a market in a rude state of health. For much of the year, market participants have acknowledged that the range of investors actively participating in Australian securitisation deals – especially in senior tranches – has narrowed, leading to tricky execution conditions.

The outcome has been that deals can be done but often only if issuers are prepared to be pragmatic on size and price. In at least some cases, the choice appears to have been to prioritise one or the other.

RedZed priced its first RMBS of the year in early July, having announced the transaction almost a month earlier. It matched its volume target with a A$500 million print but had to widen pricing margins from initial guidance across the capital structure – by 5-10 basis points in the senior notes and as much as 85 basis points in the most junior tranches. Despite the tough execution environment, Rick Li, RedZed’s Sydney-based treasurer, says the issuer is satisfied with the outcome. “Given the timing and volatility, we are pleased to have been able to issue the amount we initially set out to achieve,” he told KangaNews after pricing.

Pepper Money took the alternative approach. On 8 July, it offered price guidance on a new RMBS with indicative volume of A$1 billion equivalent including a US dollar tranche. It held pricing on the transaction’s senior notes and achieved tighter margins on the mezzanine tranches at pricing on 20 July, but reduced the overall size of the deal to A$500 million in domestic currency only.

It has been hard to make a definitive call on pricing margins for nonbank securitisation in 2022, because of market volatility and because issuers have typically been willing to split their senior tranches into short- and longer-tenor components to find demand. But it is undoubtedly true that senior notes have required a margin of at least 150 basis points, and often 170 basis points or more, over swap to find a bid. Even nonconforming RMBS deals had tightened below the 100 basis points over swap floor in late 2021, by contrast.

Speaking at an Australian Securitisation Forum investor event in London in June, James Austin, Firstmac’s Brisbane-based chief financial officer, said: “Investor depth has not vanished. They are there – the issue is uncertainty about pricing and thus reduced confidence in the bookbuild process, so ticket sizes are smaller. I do not recall a time in which price discovery has been as difficult as it is now.”

Rob Camilleri, partner and head of structured credit at Realm Investment House in Melbourne, adds: “RMBS instruments offer a very expensive funding profile at the moment. Some prime issuers are finding it challenging to secure funding at sustainable rates.”

“In the short term, we might see a bump in refinancing activity as borrowers look around for a better deal from the alternative lenders. As borrowers’ finances become more complex, we could see them look to the nonbanks.”

Button TextRETURNING VALUE

While the market is clearly still challenging, there were some positive signs by August and early September. In particular, La Trobe Financial’s return to RMBS issuance and the latest deal from Pepper suggested a more positive tone.

La Trobe Financial priced its deal on 26 July, with a margin of 100 basis points over BBSW on the short-tenor senior notes – the tight end of a 10 basis point marketing range – and 175 basis points over BBSW – in line with guidance – on the long-tenor senior tranche. Significantly, La Trobe Financial upsized the deal to A$750 million from A$500 million in just one day between launch and pricing.

Pepper achieved an even greater upsize, to A$1.25 billion from A$650 million, while holding pricing stable on the RMBS it priced on 1 September. The margin on the single tranche of senior notes was 155 basis points over BBSW.

“Market conditions are choppy in all asset classes but we are seeing signs of stability emerging, evidenced by investor demand for our most recent transaction,” Paul Brown, La Trobe Financial’s Melbourne-based treasurer, told KangaNews. “RMBS spreads are wider than historical norms but we expect a tightening bias to emerge for high-quality issuers such as La Trobe Financial as central banks reach terminal interest rates.”

While the full impact of the accelerated RBA hiking process is still working its way through the system, analysts are starting to coalesce around the idea that the hikes may not be endless. CBA, for instance, expects the cash rate will peak at around 2.6 per cent in the coming months and that the RBA will cut in the second half of 2023. A key driver of this low peak and relatively swift reversal is falling house prices: CBA expects a 15 per cent national peak-to-trough correction.

Coming off a period in which global credit pricing was “probably too tight”, Dylan Bourke, managing director and portfolio manager at Kapstream Capital in Sydney, says spreads had moved back into a reasonably attractive range by late August. “Australian nonbank mezzanine structured debt has always been a standout for its low default risk and very attractive credit spread,” he comments. “Total returns in investments like this look better than they did 12 months ago.”

Bourke believes now is a reasonable time to start participating in this part of the RMBS capital stack, while keeping an eye on signals from the US that indicate a global rather than a technical recession.

Camilleri agrees that investors are finding value around the middle mezzanine levels of deal structures. “There is a pick-up in yield and enhanced liquidity, so it makes sense to participate in this part of the capital structure,” he explains.

Wider spreads on triple-A notes should also start to attract investors. For offshore accounts in particular, the story of 2022 as it relates to Australian securitisation has not been one of concern about credit but a simple relative-value equation. Simply put, alternative product – such as collateralised debt obligations – have offered more headline yield than Australian triple-A securitisation.

By late Q3, Australian triple-A-rated nonconforming RMBS tranches were pricing at levels seen in double- or single-A rated debt at the beginning of the year, says Tally Dewan, financials and securitisation desk strategist at CBA in Sydney. “Investors can have much better risk and liquidity at the same margin,” she comments.

Camilleri is also relatively positive about the nonbank value proposition. “In the short term, the nonbanks will find it challenging to compete. But conditions will improve once they move through this part of the cycle and are able to reprice their mortgage product.”

While rates are higher and the property market is slower, it is not doom and gloom for RMBS. “The market has adapted and continued to function,” says Hanton. “To overcome execution risks, issuers have to have lower tranches shored up before they launch – but this has been possible.”

In fact, the specifics of changing demand might actually put nonbank funding on a more secure footing for the future. The big change in the triple-A space, market users agree, has been that banks have not been cornerstoning deals to the same extent they were previously. This has meant the market has become more reliant on real money, something the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority has wanted for a long time.

“The Australian securitisation market has been tested, but to this point one has to say it has earned something better than a pass mark in the sense of coping with what has been thrown at it,” Hanton concludes.

Nor have deal structures been stretched by a more challenging funding market. For instance, S&P’s Sydney-based senior director and sector lead, structured finance ratings, Narelle Coneybeare, is sanguine on the sector. She explains that transactions already include more than the minimum structural protections and senior notes have a lot more credit enhancement. “We haven’t observed pressure to reduce the level of enhancement to date,” she reveals.

Indeed, the new environment offers nonbank lenders opportunities as well as risks – in particular from the flow of borrowers coming off fixed-rate loans largely taken out from banks. “In the short term, we might see a bump in refinancing activity as borrowers look around for a better deal from the alternative lenders,” Coneybeare says. “As borrowers’ finances become more complex, we could see them look to the nonbanks."

nonbank Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's eighth annual guide to the business and funding trends in Australia's nonbank financial-institution sector.