Kāinga Ora’s exit leaves a hole in New Zealand debt market

Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities will no longer access funding in its own name, with the agency instead to be funded directly through the New Zealand government. Local market participants say the move is understandable though the loss of a programmatic agency borrower – with a leadership position in the sustainable finance space – will be a blow.

Katheryn Lee Staff Writer KANGANEWS

The notification that Kāinga Ora’s funding would be folded into the sovereign programme came through on the morning of 11 November. Although KangaNews understands some within the agency were aware this change was in the offing, most market participants were surprised by the announcement.

The announcement hands over the responsibility for funding Kāinga Ora’s build programme to New Zealand Debt Management (NZDM). Many suspected such a change to the agency’s funding arrangements could be on the cards once the New Zealand government changed its net debt indicator to include Crown entity borrowers. The June 2022 decision brings assets held by government-owned entities – like NZ Super – onto the Crown balance sheet but also makes it responsible for equivalent liabilities, like those of Kāinga Ora.

Market users say centralising funding arrangements makes some sense under this new alignment of assets and liabilities. But they would have expected such a significant shift to go through a more thorough and, potentially, public process. “To spring it on the market completely out of the blue was a little surprising,” one trader tells KangaNews. “When what is included under the government debt umbrella changed we thought this should happen, but we assumed it would take government some time to work it out and then implement it. It was no great surprise, in other words, but the timing was.”

In a document explaining the rationale for the decision, New Zealand Treasury notes that Kāinga Ora originally advocated for its own bond issuance programme on the basis that it offered “financing certainty and flexibility” and “improved long-term planning”.

However, having reviewed the efficiency of the current arrangements, Treasury says the government has concluded that these “benefits can be delivered at lower cost by having Kāinga Ora borrow from the Crown via NZDM”.

The statement continues: “The cost to Kāinga Ora of private borrowing is at a premium to the borrowing cost of NZDM. This reflects the smaller investor pool and lower liquidity of the private borrowing programme of Kāinga Ora. The change to NZDM will lower borrowing costs, both for Kāinga Ora and at a whole-of-Crown level.”

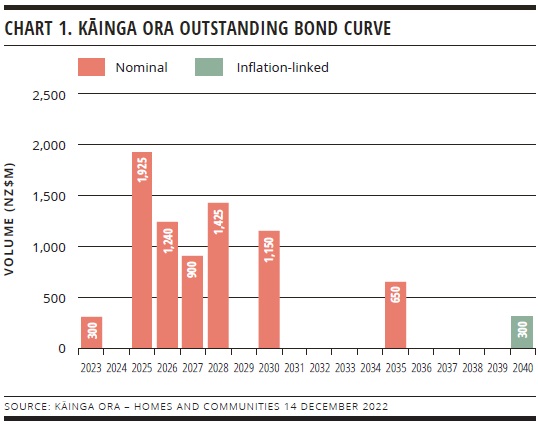

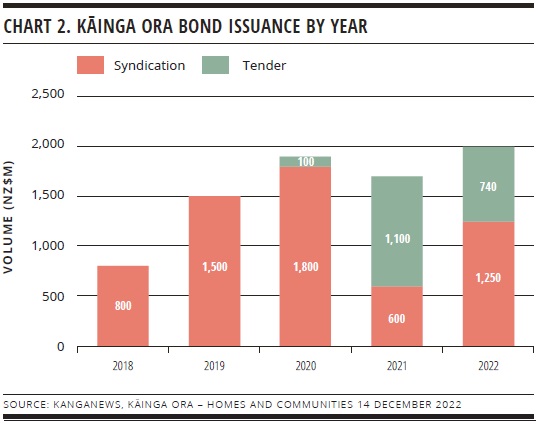

Through its Housing New Zealand entity, Kāinga Ora has been a regular bond issuer since it returned to the capital market in 2018. Since then it has grown its outstanding issuance volume to nearly NZ$8 billion (US$5.7 billion), three quarters of it issued via syndication and the rest by tender (see charts 1 and 2). It also helped pioneer sustainability-aligned issuance in New Zealand through its wellbeing bond issuance and post-issuance reporting.

There are no guarantees

Some market users – including within the agency – believe it would have made sense for New Zealand Treasury to explore other options before dissolving the Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities funding programme completely, such as an explicit government guarantee. The idea appears to have been a nonstarter, however.

The rationale behind an explicit guarantee is that it would have helped Kāinga Ora achieve an ongoing cost of funding much closer the sovereign curve while maintaining the presence of a diverse issuer name and the sustainable-finance innovation Kāinga Ora was driving.

If the government had pursued such an option, it would have put Kāinga Ora in a similar position to Australia’s National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC), which uses an explicit guarantee to issue debt in the capital markets and then on-lends to community housing providers (CHPs). Kāinga Ora issued its own debt and operated its own build programme rather than lending to CHPs.

However, the suggestion that New Zealand Treasury was opposed in principle to Kāinga Ora’s existence as a standalone issuer meant the pursuit of an explicit sovereign guarantee was always likely to be an uphill battle. One source familiar with the dialogue between agencies says the proposal to explore a sovereign guarantee in detail never gained traction.

Furthermore, some market participants argue that an explicit guarantee would not have made enough of a difference to be a worthwhile project. “Kāinga Ora still would have traded at a premium,” one says. “Even under its own name, it was pretty much an implicit guarantee anyway – if Kāinga Ora was to fail, investors would be pretty confident of getting their money back.”

If the agency had stepped up to an explicit guarantee it would still likely have traded at a margin over government – albeit a smaller one. “If you’re going to go that way you might as well fold the whole thing into the government programme and save as much money as possible,” the source concludes.

Even in Australia, the explicit guarantee is likely not set in stone. A statutory review into NHFIC’s operations published in August 2021 reports that the Commonwealth guarantee of NHFIC’s liabilities has been “central” to its success in raising finance in the debt capital market, but that it is “not entirely costless”, noting a range of reasons including that it “weakens the Commonwealth’s financial strength in the eyes of credit rating agencies and investors”.

The statutory review goes on to say stakeholders overwhelmingly agree on the importance of maintaining the guarantee until the programme reaches a greater level of maturity. But it adds that that the long-term goal should be for the agency to be able to raise low-cost and long-term finance without the assistance of the guarantee.

CENTRALISATION RATIONALE

KangaNews understands the demise of Kāinga Ora as an independent issuer has a back story that begins well before the amalgamation of Crown assets and liabilities in June. Sources familiar with the developments suggest Treasury has never been in favour of Kāinga Ora conducting its own funding and was ready to use any rationale to recommend the end of the programme. Treasury routinely opposed Kāinga Ora’s funding plans throughout its time as an issuer, for instance. There was little interest in exploring alternative or compromise funding arrangements that might have saved the Kāinga Ora name in capital markets (see box on this page).

However, while market participants express shock at the way the announcement was made, there is a general acceptance of the rationale behind the move. Not only does it make economic sense for the agency to have access to cheaper funding, but there is some confidence the overall market capacity for New Zealand government bonds has grown – which suggests absorbing Kāinga Ora’s funding should be manageable.

NZDM released an updated forward funding forecast on 14 December. The NZ$28 billion issuance expectation for the current financial year is NZ$3 billion up on the estimate published following the Crown budget release in May and the debt management agency ascribes part of the increase to the absorption of the Kāinga Ora programme. Still, the increase is only around 10 per cent in total.

NZDM issues more cheaply than Kāinga Ora, and market participants say the value of this should not be lost. “The extra margin Kāinga Ora paid on its debt can build a few more houses for Kiwis, so from that perspective this is a good development. But from a debt capital markets perspective it is a bit of a shame,” notes Fergus McDonald, head of bonds and currency at Nikko Asset Management in Auckland.

The challenge for Kāinga Ora as an independent issuer is that the primary advantage of centralising funding – a tighter margin across the board – is readily apparent and quantifiable, whereas the up side of having separate issuers is more nebulous. It includes Kāinga Ora contributing to a more diverse capital market with additional innovation, especially in the sustainable finance sector (see box below).

Iain Cox, head of fixed income and cash at ANZ Investments in Auckland, says that as a taxpayer he agrees with the decision, but as an investor he is disappointed. Not only did the bonds offer government risk with a spread, he notes, but Kāinga Ora’s regular tenders were also a helpful indicator of pricing and liquidity. He adds that the move could also cause a complication for bank balance sheets, especially as the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) completes its liquidity review – a three-year process it launched in February 2022 to help limit the risk of financial institution liquidity issues.

“Not only does it take away a high-quality issuer the banks could have on balance sheets as part of their liquid assets portfolios, but the RBNZ’s liquidity review could potentially lead to a tightening of the assets they can hold, which again would be a blow for the banks,” Cox explains.

Glen Sorensen, director, syndicate at ANZ in Wellington, says the loss of a regular tender schedule will reduce price transparency in New Zealand. But a bigger programme should increase liquidity in the New Zealand government bond (NZGB) curve. “Investors looking for high-grade credit that offers a pick up to NZGBs have obviously had their local options reduced,” Sorensen tells KangaNews. “On the flip side, incorporating what was previously Kāinga Ora borrowing into the NZGB programme increases NZGB volume and arguably assists liquidity, which is a key consideration – particularly for offshore investors.”

Green light goes red as New Zealand loses its biggest ESG issuer

Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities was New Zealand’s largest issuer of green, social and sustainability bonds as well as a global pioneer in the sustainability bond space. Its departure should add capacity to New Zealand Debt Management’s green-bond programme but it is not a like-for-like transfer.

Kāinga Ora returned to the market in 2018 as a socialbond issuer. This was already unique, and the issuer upped its innovation further a year later when it published its wellbeing bond framework and reclassified all existing and future issuance as wellbeing bonds – a sustainability-bond product combining green and social use of proceeds.

Now Kāinga Ora will no longer be issuing in its own name, the New Zealand market will lose this unique source of issuance – which has also acted as a guiding light for other issuers, including corporate names, that want to enter the sustainable debt market.

One local sustainable finance banker tells KangaNews: “First and foremost we should acknowledge the incredible work done by Kāinga Ora’s treasury team – hats off to them for their innovation and leadership. It is a loss, because the agency has been such a regular issuer. But I think it is up to us to push on the doors Kāinga Ora has unlocked. It is also an opportunity for the government to increase its green – or sustainable – bond curve.”

The immediate challenge for using Kāinga Ora’s assets to boost sovereign issuance capacity is that New Zealand Debt Management has published a green-bond framework. This is wideranging and diverse but will still need to be updated to take advantage of social assets.

New Zealand only issued its first sovereign green bond in November, but expanding the programme could already be on the cards. At an address at the KangaNews New Zealand Debt Capital Market Summit in September 2022, Grant Robertson, New Zealand’s minister of finance, highlighted the option.

“We wanted to do [the green bond] absolutely properly and well. It also meant we could look at green-bond frameworks around the world and draw lessons,” he said. “A wider sustainability framework is an interesting idea and I imagine in the future we will get there.”

CREDIBILITY BLOW

There is also the wider issue of government credibility. Cox says the latest Kāinga Ora decision is not the first time the government has made a swing decision in regard to the agency. “Kāinga Ora started off as a NZ$3 billion balance sheet, then it was doubled in a single announcement and now it has disappeared. It shows the amount of risk in investing in political institutions,”he tells KangaNews.

While the issue is now moot for Kāinga Ora, it could whip up a headwind for whatever funding outcome emerges from the government’s Three Waters plan. Already mired in political controversy – the opposition National Party has vowed to shelve the reforms if it wins power in 2023 – a new funding entity built on shaky political commitment could struggle to maximise investor support.

In early December, the New Zealand government put forward legislation that New Zealand’s water infrastructure and services would be managed by four new publicly owned water entities, with these replacing the services currently managed by 67 councils. However, it is still unclear how the projected NZ$120-185 billion in investment needed over a 30-year period will be financed.

Market participants agree that having a second high-grade issuer, in the form of Kāinga Ora, was a useful development for the market. Three Waters could in theory be a worthy substitute. Depending on how the government chooses to pursue the programme, if it does at all, there is a chance it could lead to the creation of a new entity that would need to secure funding from the capital market.

Water infrastructure could also be funded off the Crown balance sheet itself, through New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency (LGFA) or, as it is now, by individual local councils. However it is funded, though, market participants insist that uncertainty will not help any reorganisation plan in capital markets.

Cox says if Three Waters goes ahead, a separate entity that operates in a similar way to the LGFA would make sense. “If the assets are owned by councils, I think it will be something along the lines of the LGFA rather than a government-like issuer,” he comments. “This is what I’m currently thinking.”

McDonald agrees that a new high-grade issuer would fill the hole left by Kāinga Ora’s exit. However, he is also cautious, pointing out that the borrowing operations could be managed in myriad ways. He tells KangaNews: “I think there is too much water to go under the bridge before we can have any certainty. But it would be a useful addition to the local market. The credit quality of a Three Waters entity would be strong, and quite closely associated with government. However, we have an election toward the end of 2023 and we do not know if Three Waters will survive whatever comes out.”

PRICING IMPACT

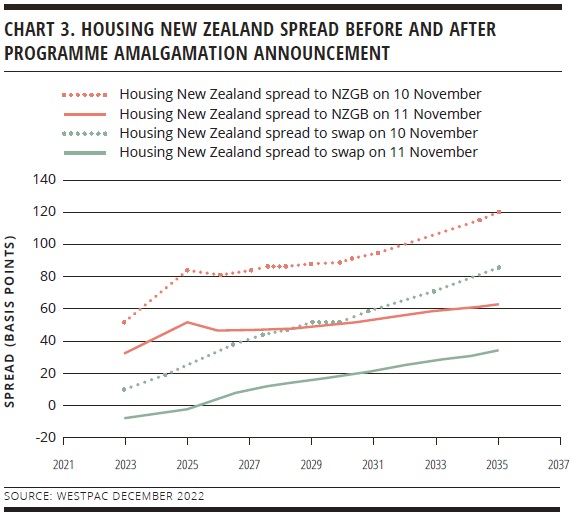

As expected, the margins on existing Housing New Zealand bonds tightened dramatically immediately after the announcement, bringing them closer to their new guarantor, the New Zealand sovereign (see chart 3). The trajectory was not locked in, however, and spreads have since edged wider – though not back to where they were.

McDonald suggests some offshore accounts sold on the first wave of tightening, fuelling the slight retreat in spread. He suspects this was mainly a profit-taking move but adds that these investors could also have been expressing a view on future liquidity. “Investors do not want to look a gift horse in the mouth and Housing New Zealand bonds have performed very strongly, so it was probably a good time to take profit,” McDonald comments. “Also, since Kāinga Ora is not going to continue to support the market by way of new issuance, perhaps international investors are concerned liquidity might dry up in future.”

There is no consensus on where pricing of the legacy issuance will land. Market users agree that Housing New Zealand bonds will continue to trade at a spread over government bonds but are not sure what it will or should be.

One source tells KangaNews spreads on the legacy bonds could contract again, while McDonald suggests the initial round of tightening may have been too quick to reflect a real conclusion on value. He offers the view that another way to look at outstanding Housing New Zealand bonds could be to compare them to global high-grade issuers with explicit sovereign guarantees that issue into New Zealand. “Rentenbank Kauris trade at a margin over swap, which suggests that perhaps Housing New Zealand came in a bit quickly.”

A lot also depends on the future risk weighting. As it stands, Housing New Zealand bonds hold a 20 per cent risk weighting – however, some say it would make sense for the RBNZ to change this to zero, to align with government bonds. Such a move would likely spur additional bank balance sheet demand and tighten spreads further.

“Having said this, Kāinga Ora debt is not the same as government debt,” McDonald adds. “It might be hard to go the additional step, to have it in the same risk weighting as government. If it did, we would expect a larger bid for the existing debt.”

Barring a change in risk weighting, one bank treasurer tells KangaNews appetite for Housing New Zealand bonds will be based on where spreads settle. “It would not be especially attractive if the bonds are tight and we have to hold additional capital compared with government risk-weighted assets.”

A Westpac research note also suggests there is potential for spreads to decline further on an outright and a relative basis simply because they have been at historically high levels. “Spreads have risen significantly over the past two months, partly due to global risk sentiment and partly due to NZGB outperformance due to inclusion in the FTSE WGBI [FTSE World Government Bond Index] benchmark,” it stated.

In the meantime, McDonald says Nikko is happy to hold the bonds. “Housing New Zealand is a core part of delivering government social housing initiatives and nothing has really changed in this respect,” he comments. “We are a more than happy holder of Housing New Zealand and we believe that, over time, it will probably contract in credit margin.”

He adds that the absence of the issuer will also add a further demand tailwind to the wider market. “One fewer quality name means New Zealand credit will likely continue to have a bid tone as investors will be looking for other types of issuer,” he explains.

HIGH-GRADE ISSUERS YEARBOOK 2023

The ultimate guide to Australian and New Zealand government-sector borrowers.