Eyes on Australia once again

At the end of October 2022, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia Global Markets Conference returned to Sydney for the first time since the pandemic. The event presents a unique opportunity for international and local investors to hear about the economies and fixed-income markets of Australia and New Zealand.

KangaNews was present throughout the three-day event in Sydney, to hear from Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) leaders, bond issuers from around the world, and other key market participants on the local economies, the fixed-income sector and the evolution of environmental, social and governance considerations.

Adam Donaldson, head of macro sales at CBA, says: “The conference’s success demonstrates the broader interest in Australia/New Zealand macromarkets and how keen both issuers and investors are to learn in detail about the opportunities in hand.”

The event also took delegates on the road, as Queensland Treasury Corporation (QTC) hosted investors in Brisbane for an update on the state’s investment and funding plans. KangaNews presents a digest of an ambitious, high-level agenda that keeps Australia and New Zealand on the global investor radar.

ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: IS AUSTRALIA DIFFERENT?

Like virtually all developed world central banks, the Reserve Bank of Australia pursued an aggressive rate-hiking path in 2022. But it was also among the first to slow the pace of rate increases, and CBA’s economists believe a gentler flightpath and a softer landing may be the most likely outcome in Australia.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) lifted the cash rate by 300 basis points between May and December – including 200 basis points of hikes in the June-September window alone. But it dialled back the monthly increments to 25 basis points from October onwards, indicating that it may feel the heavy lifting has been done.

The CBA economics and strategists teams are inclined to agree. The house view is that other central banks will soon follow the RBA into less hawkish stances, with a reversal in policy direction to follow sooner than many anticipate.

“For 2023, one of the big developments for the global economy and markets will be, in our view, what we might call ‘the pivot.’ That is, when will central banks feel like they have got on top of inflation – today’s problem – and switch to a focus on tomorrow’s problem,” said Stephen Halmarick, chief economist at CBA. “The first phase will be the slowdown in the pace of tightening, then an end to the tightening cycle and then, eventually, the start of some monetary policy easing.”

CBA’s base case is that all of this could happen over the course of 2023. Indeed, the bank is pencilling in rate cuts before the end of 2023 in the US and Australia. On the key economic indicators, CBA is forecasting unemployment to remain around the record low level of 3.5 per cent into the new year before climbing only gradually, to 4.25 per cent, in 2023. Headline inflation should peak at 7.75 per cent then decline fairly quickly in 2023 – assisted by wages growth that will only increase to 3.5 per cent from 3 per cent.

Gareth Aird, CBA’s head of Australian economics, admitted that this is a relatively benign outlook that depends on something of a Goldilocks scenario. The bottom line is that the bank’s relatively positive economic outlook depends on the RBA not overshooting its monetary tightening.

It could be hard for the central bank to hold its relatively dovish line in a world where peers, including the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and US Federal Reserve, are freely acknowledging that they may need to push their economies into recession to curb inflation. For most of 2022, there were few signs of RBA rate hikes biting the household balance sheet: Aird acknowledged that retail spending and employment data have barely flickered as the cash rate climbed.

NATIONAL DIFFERENCES

On the other hand, a deeper look at the data is enough to convince Aird that higher interest rates are starting to have a cooling impact on demand. He explained: “Inflation in Australia is different from where, for example, the US is right now. In Australia, inflation is split between goods and services, which is a good story. Services inflation is well correlated with wages growth, and Australia has not experienced this to the same extent as other jurisdictions.”

In other words, an inflation outbreak that started in supply lines and commodity markets appears now to have spread into wages growth in countries like the US but not Australia. Here, wages growth continues to lag inflation – and this gives the RBA a better chance of managing a soft landing without having to hike to the point of crushing demand completely.

The RBA is aware of this nuance. Christopher Kent, the reserve bank’s assistant governor, financial markets, noted at the event that “while wages growth has picked up in Australia from the low levels of recent years, it remains lower than in many other advanced economies”. Meanwhile, Aird revealed that the RBA has engaged with CBA about the latter’s wages indicator, which tracks payments into 275,000 CBA accounts and suggests wages growth is somewhat lower than the level implied by business surveys. Aird believes the RBA “is comfortable with the narrative that wages growth is different in Australia from other jurisdictions”.

There is also the probability that the impact of earlier RBA hikes on demand has not yet played out in full. Research by the CBA team earlier in 2022 suggested a lag of at least 2-3 months between an interest rate hike and the impact on household balance sheets, thanks to a range of technical factors. This means the last of the RBA’s 50 basis point increases will only feed through to borrowers around Christmas and the subsequent 25 basis point rate hikes in October, November and December will continue to bite well into the new year.

Calendar 2022 may be too soon to know how significant the impact of rapid rate hikes will be – so it is possible the RBA has already gone far enough. “The early signs of the impact of higher policy rates are being seen in the drop in house prices and housing activity,” said Martin Whetton, CBA’s head of fixed income and rates strategy. “Households are starting to be tested on this front as their interest costs rise sharply and as they move off the fixed rates that were a feature of the mortgage market in recent years.”

This pressure is particularly acute in Australia, Aird continued, as the country continues to have among the highest levels of household indebtedness in the world – despite a pickup in savings rates during the pandemic. “This means that when rates go up the impact on disposable income is very, very large,” Aird said. “The outcome is that a cash rate of 2.5 per cent takes mortgage repayments to a record high as a share of household income. The RBA recognises this.”

AUSTRALIAN ISSUERS: MANAGING THROUGH 2022 AND LOOKING AHEAD

The Australian sovereign and semi-government market has held up well across waves of challenges in the past decade and a half. While the normalisation of market dynamics after many years of volatility-suppressing fiscal policy has changed the landscape again – and led to a tough year for most bond market participants – the Australian high-grade sector once again rolled with the punches.

“We all knew 2022 was going to be a rough ride,” said Mitch Grosser, head of trading at CBA. “Unwinding zero rates and abandoning yield curve control took away the biggest bond buyers in the market, particularly the cessation of some of the biggest bond buying programmes such as in Europe. This was never going to be particularly smooth. What many would not have expected was that rates market volatility would match all-time highs – including from the global financial crisis.”

Virtually all asset classes were swept up in the turmoil of 2022. Liquidity conditions were dominated throughout the year by the great unwind from the QE years. “This isn’t a typical market dislocation, in other words. It is a fundamental repricing, and one that needs to happen,” Grosser concluded.

For programmatic issuers like the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) and the local states, market conditions like these provide unavoidable challenges. With substantial programmes to fund, bond supply has to continue even if investor confidence wobbles and pricing conditions are suboptimal. To some extent the response can only be to roll with the punches. Matthew Wheadon, head of funding and liquidity at the AOFM, said: “A feature of 2022 has been that the Australian market has imported volatility from overseas. This will happen from time to time. Our job is not to become a source of problems or of dislocation in the market through our own actions.”

The reality is that difficult conditions make investors retreat even when – as with the Australian government complex – there is no fundamental credit issue. For instance, Daniel Chandler, head of funding and sustainability at New South Wales Treasury Corporation, revealed that offshore investor participation in the issuer’s syndications was typically just more than 10 per cent in 2022, versus a long-run average of 20 per cent.

“There is a lot going on all over the world, so it should not be surprising that investors are more focused on their core and less on markets that are further away,” Chandler explained. “Feedback confirms there is no issue with our credit and indeed some investors have started to like the spread Australian semi-governments offer relative to the sovereign. Caution is just a product of where we are in the cycle.”

On the other hand, Paul Kelly, head of markets at Treasury Corporation of Victoria, noted the strong support local bank balance sheets provided semi-government issuers in 2022. These accounts have been confronting significant changes in their high-quality liquid asset holdings – a process Kelly suggested will be ongoing for some time and which provides a clear positive for local sovereign sector issuers.

CONSISTENCY AND FLEXIBILITY

In this sort of environment, issuers have been trying to walk the line of reliable behaviour and a flexible approach to fulfilling a funding programme. This means maintaining contact with investors even when they are less active, and responding to market conditions to execute primary issuance without being excessively opportunistic.

“Volatility is there right now, particularly for offshore investors. But it is important that we have a consistent, regular, transparent approach to investor engagement,” said Jose Fajardo, head of funding and liquidity at Queensland Treasury Corporation. “Maybe right now is not the right time for them. But we have seen conditions turn in the past and we know that investors are very engaged in the outreach we have done.”

Wheadon also emphasised the importance of consistency in the funding programme itself. “The cornerstone of the AOFM’s approach to debt management is that we believe cost effectiveness and continuity of access to finance stems from a well functioning Commonwealth government bond market, which has deep liquidity and broad-based participation from a large group of investors and intermediaries. We frame our issuance decisions around this principle, which means we don’t try to be opportunistic – pushing more bonds into the market because we like the rate on a certain day, for instance.”

At the margin, however, issuers say challenging market conditions mean a flexible approach to execution is key. This could mean, for instance, being prepared to adapt issuance timing to find the best available conditions.

Kaylene Gulich, chief executive at Western Australian Treasury Corporation, explained: “There are fewer execution windows available in particular because the market is much more sensitive to data releases at the moment. One of the other challenges is that we are all looking at the same windows as opportunities to issue into the same market. But we continue to manage this really well as a collective group – as we have done over a long period.”

South Australian Government Financing Authority’s director, treasury services, Andrew Kennedy, added: “We are price takers and we have programmes we need to meet. In an environment like today’s, coming to market involves having the right balance between our own balance sheet management, how we fund our clients and investor requirements – volume and tenor. It is a question of flexibility, including the method by which we come to market and the timing of syndicated transactions.”

For example, Kennedy explained that concentration of bids from bank balance sheets means issuers need to be somewhat flexible on pricing to meet asset-swap targets, with somewhat more concession included in transactions than there was 12-18 months ago.

Chandler also highlighted TCorp’s decision to execute its last two syndicated transactions intraday. The issuer had to decide whether there would be sufficient incremental demand overnight to take the risk of market disruption, and it concluded on these two occasions that the potential benefits did not outweigh the risks.

Fajardo said it has been very helpful, in a risk-off environment, to have the flexibility to issue via reverse enquiry or to place floating-rate notes. “On the other hand, syndicated transactions continue to provide the broadest investor base,” he added. “We try to capture this diversity through the marketing range for pricing, and momentum in the trade dictates where we land within it.”

Overall, issuers say they are positive about the market outlook. Kennedy told delegates at the CBA conference: “The dynamics of the market are shifting, sometimes on a daily basis, and volatility continues to make bringing transactions to market tricky. But we are there to issue and investors are there to invest: superannuation funds keep growing, as do requirements for bank regulatory capital. The supply and demand dynamic still offsets – it is just a question of finding the balance of what will work at any point in time.”

Rates certainty will brighten the picture, too. Kelly revealed that investors TCV recently saw in Europe were typically waiting to get further through the rate-hiking cycle before recommitting to the sector. “The further we get through the cycle – the closer to a clear end point – the more we will see real-money investors engaging with their allocation to the government sector.”

There is also the probability that the impact of earlier RBA hikes on demand has not yet played out in full. Research by the CBA team earlier in 2022 suggested a lag of at least 2-3 months between an interest rate hike and the impact on household balance sheets, thanks to a range of technical factors. This means the last of the RBA’s 50 basis point increases will only feed through to borrowers around Christmas and the subsequent 25 basis point rate hikes in October, November and December will continue to bite well into the new year.

Calendar 2022 may be too soon to know how significant the impact of rapid rate hikes will be – so it is possible the RBA has already gone far enough. “The early signs of the impact of higher policy rates are being seen in the drop in house prices and housing activity,” said Martin Whetton, CBA’s head of fixed income and rates strategy. “Households are starting to be tested on this front as their interest costs rise sharply and as they move off the fixed rates that were a feature of the mortgage market in recent years.”

This pressure is particularly acute in Australia, Aird continued, as the country continues to have among the highest levels of household indebtedness in the world – despite a pickup in savings rates during the pandemic. “This means that when rates go up the impact on disposable income is very, very large,” Aird said. “The outcome is that a cash rate of 2.5 per cent takes mortgage repayments to a record high as a share of household income. The RBA recognises this.”

The big bank view

During the CBA conference, Matt Comyn, the bank’s chief executive, sat down with Chris McLachlan, executive general manager, global markets at CBA in Sydney, for a fireside chat that took in the global economic situation, CBA’s commitment to sustainability and the availability of capital to support the institutional banking and markets division.

McLachlan I have run out of adjectives to describe volatility over the past year, but October was another turbulent month for global markets. What is your view on the outlook for the global economy?

COMYN There has been an enormous amount of volatility globally, particularly but not limited to rates and commodities. I have had the opportunity to travel a lot recently, including to the US and Europe, and it is fair to say it all looks fairly negative. Our current view sees the US, UK, Europe and Japan going into recession in 2023, though we do not expect the same in Australia.

A combination of continued and persistent monetary policy tightening will be required in the US. So far there is nothing to show that inflation is not still a big risk there, and the price of reigning inflation in will be a slowdown in economic activity. The outlook in Europe was very dark when I was there in September, and the UK in particular is clearly confronting very high inflation.

When I was last in Canberra, I met with a number of officials and we went through some of the economic data. The risk statement is that there will be a number of energy price hikes, next year in particular, that will flow into consumption more broadly.

Then again, these hikes may be 15-30 per cent – whereas when I visited Germany recently some of the locals are talking about a 600 per cent increase in energy prices. You can imagine what that would be like domestically. We certainly retain our relatively optimistic view on Australia. There are not too many parts of the globe we would like to trade places with, economically or politically.

The other thing is China: it is clearly an extremely important trading partner and is also important to many of our customers. The recent loosening of COVID-zero policies in China is of real interest.

We have been more cautious on how we see New Zealand versus Australia for some time – particularly with where we see the terminal cash rate having to go to get inflation under control. Wages growth also feels as if it is flowing through at a much faster clip in New Zealand than it is in Australia.

McLachlan What is the downside risk to the relatively positive outlook on Australia?

COMYN We did a lot of work in the lead up to our full year results in August, including across all our business areas and the treasury team. We were surprised to see the effects of tightening in some areas relative to what we had expected.

One of these was consumer confidence, which had already plummeted. We were doing our own qualitative surveys at the time, too, across retail and business customers. In retail especially, the mood was very negative.

We were able to share some of this data with policymakers here in Australia. We had anticipated spending and consumption would come off, and we thought we could see early signs of it pulling back – particularly in higher-income households and those with high mortgage debt, which should not have been a surprise.

The biggest surprise was that spending looks to have improved in October and in the big sales in late November, before edging lower again in early December. On a national level, nominal spending remains quite strong.

We put this down to a number of factors. It can be counterintuitive how long monetary policy takes to flow through, particularly to households with debt. For most, it is three months from the announcement of an RBA rate hike until it translates to a change in the minimum mortgage repayment. This means we are only about half-way through the total monetary policy tightening. Even based on this, however, we would have expected more of an impact by now. But business and consumption are still strong – particularly in the services sector, where people are not constraining their spending.

However, it is not uncommon in rate hiking cycles for business conditions to stay firm, and while we can’t see it in the data there seems to be some softness for customers in the discretionary end – in white goods, for instance, which have been strong for more than two years.

When we speak to business customers, we say spending will stay strong until at least the end of the calendar year. I think what happens in the post-Christmas period will be interesting – but, from what we have seen, everything still looks relatively good. On the other hand, the labour market has hit the peak and is not as strong as we were expecting.

Lead indicators from job ads and salaries seem to be softening. There have been views about businesses indexing wage growth to headline inflation, but we are not seeing it. Across a large cohort of customers, we are only seeing wage growth of around 3 per cent or slightly above – it is a lot less than in New Zealand and there is not a lot of evidence of a wage-price spiral breakout.

McLachlan There is growing focus on what banks are doing in the environmental, social and governance space. What is CBA’s focus?

COMYN We are doing a lot, but I will try to give a short version. Fundamentally, we have been very clear about our ambition and commitment to the Net Zero Banking Alliance and 1.5 degree pathway.

Within this, we have published a standalone climate report for the first time, which discloses our progress against the 1.5 degree scenario across the top emitting sectors. As a ballpark, this is 1 per cent of our balance sheet but 27 per cent of our scope-three emissions. We are going to extend these pathways out to other sectors, too.

We have also been doing a lot of work with CSIRO [Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation] to publish Australia-specific pathways, because a lot of the international scenarios do not tailor to the domestic situation – for example, the power generation mix here is very different.

There are also things we are doing for customers, including developing a range of products to help retail investors fund solar panels and batteries at a 1 per cent fixed rate.

Carbon markets is another area we are committed to building out; we view it as an important strategic focus with a lot of potential domestically. Our customer base gives us access to a large and valuable pool of potential carbon credits, and as various mechanisms come into place through the federal budget there will be increasing demand. We expect this market to develop quite substantially.

The conversation has moved on from reporting. It has been a very important task for us as an institution, and of course we are yet to publish our full range of scope-three emissions. But we are now very much trying to play a leadership role in what we think the overall transition scenario should look like.

We want to act in the country’s best interest and support capital allocation into sectors that require significant investment in new and emerging technologies as those pathways are brought into reality.

Audience question Regulation is a trade-off between liquidity and financial stability Do banks today have room to allocate more capital to market making through trading desks?

COMYN Personally, I think it’s unlikely that much of the regulation in this area is going to be unwound or reduced. Fundamentally, most of the restrictions that have been put on, particularly from a trading perspective – across global banks – are absolutely here to stay.

Our perspective within global markets is that of course we want to operate within limits and reduce risk. But if there are opportunities to both support clients and also deliver better returns for our owners we are absolutely prepared to allocate additional capital to them.

We have embarked on a substantial investment in technology, systems and reporting. Real-time reporting comes with some complexities. But when we have the right system to model so we can both generate and justify good decisions, there should not be a restraint on doing so.

QUEENSLAND GETS SET FOR NEW WAVE OF INVESTMENT

After three days in Sydney, delegates at the CBA Global Markets Conference travelled to Brisbane for an update on the Queensland economy, hosted by Queensland Treasury Corporation. They heard about a state that is looking forward to the next decade with optimism, including plans for low-carbon transition and the 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Queensland is expected to maintain consistent growth despite challenges to the world and state economies. In tune with its track record of resilience, the state has bounced back strongly from the pandemic: its domestic economy is 9.1 per cent larger than it was before COVID-19, it has added more than 200,000 jobs since the start of the pandemic and it was the first Australian state to return to budget surplus.

“Despite Omicron, localised flooding, and the impact of energy prices and inflation globally, Queensland [growth] is still tracking above the national average,” said the state’s under treasurer, Leon Allen. “Queensland’s strong health outcomes, job opportunities and relative housing affordability has led to a surge in net interstate migration since the pandemic began. Business investment has also rebounded since the first year of the pandemic, with the value of known investment projects trending upwards.”

Queensland also has two new and significant investment drivers. One is the need to decarbonise the state economy, which is the core goal of the state government’s September 2022 Energy and Jobs Plan. The other is the Olympic and Paralympic Games, which are coming to Brisbane in 2032 and will drive business investment from the middle of the current decade.

“Just as we had the courage to go for the Olympics, we have the capacity and the ability to transition our economy to one that moves to net zero. The first major stage is decarbonising our energy system,” said the state’s treasurer, Cameron Dick.

Environmental transition poses unique challenges for Queensland as its economy has always benefited from the contribution of the natural resources sector. Although no single industry is responsible for more than 10 per cent of the state economy, Paul Martyn, director general of Queensland’s Department of Energy and Public Works, noted that it is important for decarbonisation to be carried out in a way that “avoids volatility and uncertainty as much as we can”.

This means balancing the needs for energy to be clean, reliable and affordable. The direction of travel is clear, however. “Queensland needs to have renewable energy at a globally competitive price to underpin the competitiveness of its export industries and also to enable industrial growth, as well as keep prices down for consumers and households,” Martyn added.

Queensland has set a timeline to transition its generation mix to 70 per cent renewable energy by 2032 and, in time, to eliminate regular reliance on coal-fired power generation.

The replacement strategy includes the SuperGrid – 1,700 kilometres of transmission to connect new renewable energy precincts with the grid – two large-scale, world-class pumped hydros to provide up to 7GW of long duration storage, and a range of other projects.

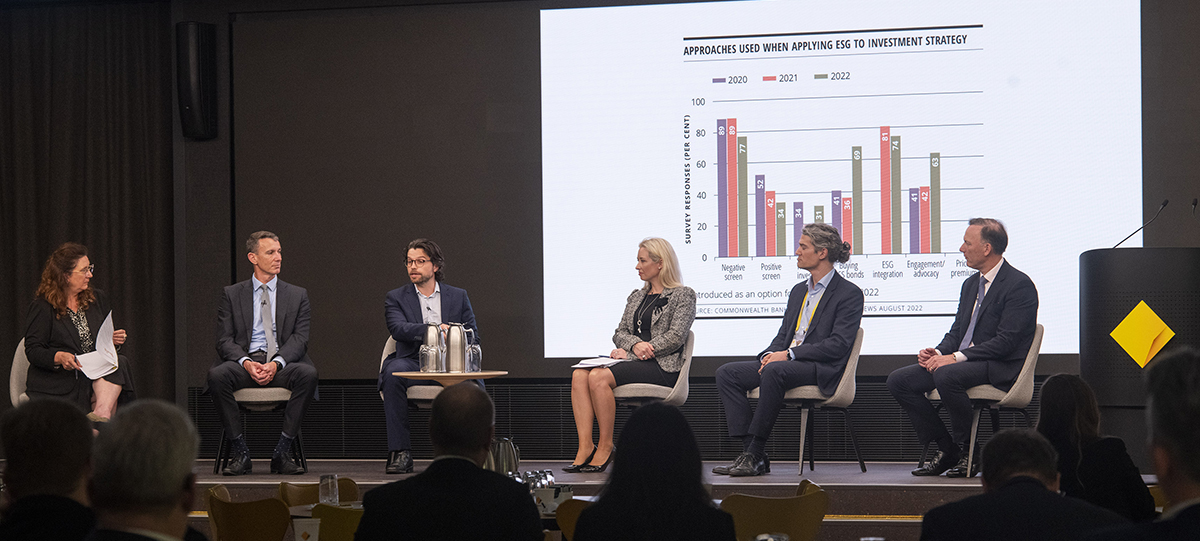

ESG’S EVER-TIGHTER GRIP ON AUSTRALIAN INVESTMENT

The volume and quality of market discourse on sustainability in the Australian capital market grows with every passing year. Sustainability is ever-more integrated with the investment process, including in the high-grade sector – traditionally one of the harder areas to deploy environmental, social and governance considerations.

Australia’s environmental, social and governance (ESG) debt market has existed for close to a decade – since the issuance of the first local green bonds, by World Bank, in 2010. While ESG-aligned issuance has been steady rather than spectacular in 2022, wider developments in the policy space could in time lead to it being regarded as a watershed year.

Charles Davis, managing director, sustainable finance and ESG at CBA, said at CBA’s conference the legislation of an emissions reduction target – of 43 per cent from 2005 to 2030 – is an important step forward. “What this does, at the highest level, is bring credibility to Australia,” he explained. “There will continue to be debate about the ambition of our targets and the way the targets are constructed – that they focus on domestic emissions rather than those that we export. But at baseline level the targets bring us broadly in line with our global peers.”

The significance for capital markets, Davis continued, is that the next phase will be adding certainty to the quantity and use of capital needed to meet these targets. Australia is a net importer of capital and a significant volume will be needed for low-carbon transition, so a clear idea of what is needed will support the task.

The message is getting through to corporate Australia, via providers of capital. Lauren Holtsbaum, CBA’s head of debt capital markets ESG origination, explained: “Investors and other stakeholders globally are increasingly demanding transparency and accountability in relation to climate-related risks and opportunities.”

Holtsbaum highlighted an Australian Council of Superannuation Investors report released in July 2022, which notes that 95 companies out of the ASX 200 have now made net zero commitments — half of them in the past year. While not yet mandatory in Australia, the report also noted that the majority of companies are now adopting and disclosing against the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, with 103 ASX 200 companies either fully or partially aligning their disclosure to the framework.

The focus among fixed-income asset managers is “engagement”. This is the means by which investors aim to influence borrower sustainability behaviour, and it is being increasingly applied across the credit and high-grade asset classes. “We are debt investors – we don’t own the company – so we have a different role,” explained Murray Ackman, ESG credit analyst at Pendal. “A big part of our role, as we see it, is trying to shape the market in a better way. This means we want information disclosures and more ESG integration, but we are also very focused on the types of bonds being issued.”

In the sovereign sector, Tamar Hamyln, principal and portfolio manager, interest rate strategies and macroeconomics at Ardea Investment Management, said: “We are in what could be a really uncomfortable situation as an investor, because we don’t have the carrot and the stick of withholding or extending capital that corporate investors enjoy – we are pretty much stuck with having to buy government bonds. This means our only channel to drive change is through engagement. However, we have actually found this to be a great positive experience and something governments are very receptive to.”

This is effectively a new facet to the investment management process. Anthony Kirkham, head of investment management and Australia and New Zealand operations at Western Asset Management, points out that third-party ESG analysis providers often only have limited coverage of Australasian entities – and none at all on private companies. “This means it is our own analysts that have to do the work to draw out the information and come up with ESG ratings – especially if we want something forward looking,” Kirkham said.

NEW ZEALAND ISSUERS WELL SET TO MANAGE ECONOMIC SLOWDOWN

New Zealand’s economic trajectory has diverged from that of its nearest neighbour, with different inputs leading to a significantly more hawkish central bank approach and outlook. Local government-sector issuers say they are positioned to manage the changing environment, including via a clutch of options with which to engage global investors.

Nick Tuffley, chief economist at ASB Bank, described New Zealand as sharing some aspects of its economic outlook with the US and others with Australia. Its main challenge comes from the fact that the former provide the greater near-term considerations: inflation, labour market tightness and wages growth and a central bank that is not yet ready to take its foot off the tightening pedal.

On the other hand, the comparisons to Australia – an open economy with growing ties to Asia – are more long-term factors. As a result, while the future is still bright for New Zealand the year ahead could be problematic. “Weaker global growth comes to New Zealand in the form of lower prices for our exports – we can’t ramp volume of agricultural exports up and down – so price is critical,” Tuffley explained. “Meanwhile, we have cost of living pressures across discretionary and essential spending.”

New Zealand’s exports are to some extent being buoyed by challenges elsewhere: the war in Ukraine, for instance, has damaged global grain supply while dairy production has been challenged by drought in many key producing regions. Overall, though, New Zealand will inevitably feel the chill of weaker global demand.

At the same time, persistent inflation and rising wages growth mean the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) has maintained its hawkish rhetoric and hiking path – which it acknowledges will hit domestic demand. The transmission mechanism is less immediate for the RBNZ than the Reserve Bank of Australia, which may also be playing a part in keeping the former on the hawkish side. Tuffley points out that while Australia’s mortgage market is overwhelmingly variable rate, New Zealanders typically borrow at rates that are fixed for up to five years.

The reckoning is not far away, however. Tuffley revealed that as many as 50 per cent of outstanding fixed-rate New Zealand mortgages are coming up to maturity in the next 12 months and will therefore have to be refinanced – inevitably at significantly higher rates. “Rate hikes will bite, but it will take a little longer – until the middle of 2023 – for them to do so,” Tuffley commented.

“Growth still looks pretty reasonable in the second half of 2022 but we expect it to grind to a halt in 2023,” Tuffley concluded. “We are not picking a recession but things are going to be pretty flat, and we expect it to be primarily households and consumer spending that bears the brunt.”

DEBT DEMAND

Given the cloudy outlook, New Zealand’s government-sector borrowers are especially pleased to note robust interest in their bonds at home and abroad. The domestic market is benefiting from ongoing system growth, and the sovereign issuer highlights two key developments that should also increase liquidity in its curve.

The first is accession to the World Government Bond Index, which happened in 2022. While careful to avoid suggesting this is a game-changer in and of itself, index inclusion should put New Zealand government bonds (NZGBs) on the radar of a wider range of global investors. Kim Martin, head of New Zealand Debt Management at the Treasury, said: “We have to acknowledge that it is difficult is to quantify flows that will result from index inclusion – we are a small part of the index and some investors may choose, even if they follow the index, simply to ignore the addition. Others might already own NZGBs off benchmark anyway. But, at the margin, there has to be a positive impact, for instance from investors that follow the index as a passive component in their portfolios.”

NZDM also debuted as a green-bond issuer in 2022. Its stated goal is for the first and subsequent green NZGBs to form part of the mainstream curve, thus maintaining current demand and simultaneously offering an option for accessing New Zealand sovereign credit for global investors with environmental, social and governance mandates.

A trade-off could be involved. While attracting new investors to its curve and thus increasing overall liquidity would clearly be a positive for NZDM, if its green bonds are unusually tightly held it could end up with a curve that offers variable secondary-market liquidity at different points. NZDM will be monitoring closely to see how the situation develops. “From a debt management perspective, it is our aim to make the green bonds as similar as possible to a nominal product – with the same legal documentation, regular coupons and volume limits of NZ$18 billion [US$12.7 billion] as a generic nominal bond line,” Martin confirmed. “Ultimately, it remains to be seen where the green bonds price in the longer term and whether they fit very smoothly on the curve.”

Mark Butcher, chief executive at New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency (LGFA), revealed that the agency has consistently been positively surprised by the capacity of the New Zealand dollar market to absorb its debt as its bonds on issue have grown. Originally thinking capacity might be around NZ$10 billion, LGFA’s outstanding volume on issue has grown to NZ$16.5 billion without apparently hitting investor limits.

On the other hand, Butcher added: “In 2020, we were assisted by the RBNZ’s QE programme. More recently, offshore investors have increased holdings as we widened on a spread over sovereign bonds, while banks have also been very active thanks to the volume of cash in the system. These have been useful market dynamics supporting demand for us.”

If capacity gets tight in New Zealand dollars, Butcher says LGFA will look to foreign-currency markets, and Australian dollars is likely to be the first option. The most likely driver is the Three Waters reform. While the outcome of this plan to consolidate water infrastructure funding from individual councils is still uncertain, one funding option among several is to include LGFA as a funding vehicle. If this happens, Butcher revealed, the issuer expects offshore funding will be all but inevitable.