Changing times unlikely to halt private debt growth in New Zealand

Private debt has emerged as an asset class globally in line with constraints on banks’ capacity and willingness to lend and as low rates compelled investors to contemplate alternative income asset classes. In New Zealand, higher interest rates are changing – but not eliminating – the return equation while market users say the opportunity set is poised to increase further.

Jeremy Chunn Editorial Consultant KANGANEWS

Australasian private debt finds itself at an interesting juncture in 2023, and while the same fundamental drivers apply on both sides of the Tasman Sea they are arguably more pronounced in New Zealand. Private debt investment has even more headroom for adoption in New Zealand while the opportunity set is, in relative terms, no less broad.

One of the primary motivating factors behind growth in the asset class over recent years – the difficulty of securing acceptable headline returns from mainstream fixed income in an ultra-low rates environment – has clearly eased. But market participants describe the previous return situation as a catalyst for private debt growth rather than an ongoing prerequisite.

For one thing, higher cash rates are a rising tide that lifts all ships in income asset classes. It may no longer be the case that higher-yielding strategies – of which private debt is typically one – are the only way to achieve acceptable absolute return. But the relative appeal of higher yield remains in place, especially when set against New Zealand’s elevated inflation.

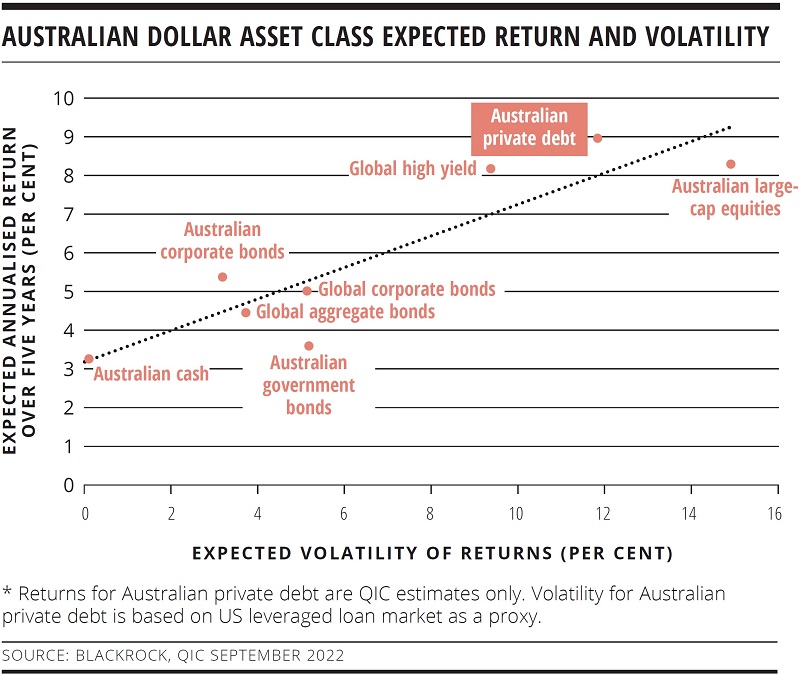

QIC research published in January suggests the private debt market in Australia and New Zealand is yielding up to 9 per cent, from 5 per cent a year earlier. Rising base rates are part of the story but wider credit premia are also playing a role. QIC suggests Australian private debt provides an expected annual return that is notably higher than traditional fixed-income asset classes and even local large-cap equities, with return volatility notably lower than the latter (see chart).

As capital constraints are tightened globally and the mainstream investment community starts to see value returning in lower-risk assets – even cash – private debt deals are being transacted higher up the capital structure and on improved credit terms. In QIC’s words, a “creditor friendly” bias should buttress the asset class against economic challenges.

Private debt has been the subject of much discussion in Australia in recent years, accompanied by the emergence of specialist investment houses and dedicated funds.

The pace of evolution has been less pronounced in New Zealand but local market users believe the acceleration phase is just beginning. “We have seen the evolution of private debt markets in the US and through Europe. The asset class is now very prevalent in Australia and it is starting to reach New Zealand,” says David McLeish, head of fixed income at Fisher Funds in Auckland.

In fact, the opportunity for private debt investment may be greater in New Zealand by virtue of the nature of its credit market and the way it is regulated. The vast majority – 80-90 per cent – of local business lending comes from the big-four banks. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) has taken a firm line on local bank capital rules, with the consequence that nonbank credit providers say the long-awaited spin-off of various types of debt from bank balance sheets is finally starting to gather pace.

“When we become a lender to a private business, the typical terms and conditions of the agreement specify a high degree of transparency of the operating environment and the financial standing of the borrower. In fact, in many cases there is a greater requirement placed on the borrower than in the public debt market."

The RBNZ's 2019 capital review delivered a significant increase to capital ratios for banks. There is a 2026 deadline to implement changes, but the consequent tightening of bank balance sheets is already influencing willingness to lend to sub-investment-grade borrowers. “We are starting to see the consequences now,” says Private Capital Group (PCG)’s Queenstown-based founder and chief executive, Paul Carman.

Richard Anderson, executive director and head of corporate and structured finance at Westpac New Zealand in Auckland, expects the local private debt market to grow as registered banks meet the RBNZ’s deadline for tighter capital requirements. The role of private debt investors could spread further if a wider range of funds and return targets emerge.

“It is possible that borrowers could tilt to debt capital markets for term funding and accept shorter tenor – 2-3 years – from bank debt. Shorter tenor will be more efficient from a funding cost perspective than going for three-plus years, which would have a capital requirement,” says Anderson.

As banks adapt to tighter regulatory requirements, capital markets are evolving to provide a wider range of borrowers with funding options. This does not necessarily mean assets falling fully into the bank or private debt sectors, as there are also growing opportunities for co-investment structures (see box on p80).

Carman estimates New Zealand’s domestic private debt market could be worth about NZ$3-10 billion (US$1.9-6.2 billion) within the next five years. This would be a small but significant share of a total business lending market – excluding property and agriculture – estimated by the RBNZ to be worth about NZ$124 billion.

The growth potential is enhanced by the fact that private debt is less tied to refinancing of mature debt facilities. Rather, it plays a growth role – often helping businesses finance ownership succession, M&A activity and other consolidation.

However, its advocates add that it is not a speculative sector. “Private debt is for companies with proven track records – not startups or venture capital,” Carman says. “We can support these businesses by providing long-term debt structured to meet their needs. This provides a series of stable and contracted interest payments that translate into predictable, low-volatility returns for our investors.”

Private debt specialists – local, regional and global – are circling the New Zealand opportunity. For instance, in August last year global investment firm Carlyle and its Australia-based credit investment arm, amicaa, launched a joint venture to build a portfolio of private debt in Australia and New Zealand. Australia’s Metrics Credit Partners launched its first New Zealand fund in March 2021.

PCG is a rare New Zealand domestic private debt specialist, and its first fund targets return of 4 per cent over the official cash rate (OCR). At the same time, some local mainstream fund managers are devoting their own resources to the opportunity. Fisher Funds late last year launched an Australasian private debt fund, with about NZ$120 million invested so far and a target of returning 3 per cent above the OCR.

“We have been investing in private funding opportunities for more than a decade but it is only in the past few months that we have seen the opportunity to launch a segregated fund,” McLeish tells KangaNews. “We believe the opportunity is here, and we would like to devote more capital to this space.”

“Private debt is for companies with proven track records – not startups or venture capital. We can support these businesses by providing long-term debt structured to meet their need. This provides a series of stable and contracted interest payments that translate into predictable, low-volatility returns for our investors."

PAUL CARMAN

UNDER THE HOOD

At Fisher Funds, all credit analysis is done in-house, which McLeish says gives the firm “a seat at the table” with borrowers to negotiate “mutually beneficial outcomes”. This is a key part of the private debt value proposition.

McLeish explains: “When we become a lender to a private business, the typical terms and conditions of the agreement specify a high degree of transparency of the operating environment and the financial standing of the borrower. In fact, in many cases there is a greater requirement placed on the borrower than in the public debt market. This means more engagement and a closer partnership with borrowers, which we think will help us better manage the credit risk in these investments over time.”

The other side of the coin, McLeish concedes, is that lending in private form means little or no prospect of secondary liquidity. “If things aren’t going to plan, private debt investors typically do not have the option simply to dispose of an asset,” he says. “They must work closely with their partners and adopt a longer-term, pragmatic and collaborative approach. It also requires resources – time and expertise in particular. Private lending is not without its drawbacks, but we firmly believe the pros outweigh the cons.”

The secondary market is generally quiet, Anderson says, unless a shift in a borrower’s business conditions causes a bank lender to seek an exit. “The secondary market for syndicated lending – investment grade or leveraged – is not that liquid as banks tend to invest and hold,” he comments.

PRIVATE DEBT FINDS ITS STRUCTURAL NICHE IN NEW ZEALAND

Changes to banks’ willingness to lend to, in particular, sub-investment grade business is the primary big-picture driver of a growing opportunity set for New Zealand private debt. But it is more a case of finding the right attachment point for third-party investors than outright replacing bank capital.

“Banks are increasingly looking for funding partners for typical business lines,” says Fisher Funds’ head of fixed income, David McLeish. “This is creating some space for private debt investors to offer some of these services.”

At this stage, says Richard Anderson, executive director and head of corporate and structured finance at Westpac New Zealand, most private debt activity tends to be in the leveraged or sub-investment-grade space where borrowers have the greatest propensity for fully drawn loans.

“Leveraged transactions are typically still bank-led,unless under a term loan B or unitranche structure,” Anderson tells KangaNews. “The majority of debt is provided by banks and we might see a fund involved for, say, NZ$20-30 million [US$12.4-18.6 million] or perhaps up to NZ$50 million. We do not typically see private debt funds in investment-grade transactions.”

Anderson notes private debt providers’ preference for term lending over revolving facilities, “so funds do not have to deal with repayments and redraws”. He confirms private debt providers often work alongside banks in leveraged transactions, adding that funds generally have greater appetite for leverage than banks.

Market participants believe banks will find ways to be participants in market evolution even as their own

capacity to lend is curtailed in some areas. McLeish cites an example where a bank might lend in secured form for three years or less in a facility that also includes longer-term funding – of 5-7 years – from a private debt provider.

Another option is two-tier loans, where a subordinated tranche goes to private credit while banks take the shorter-term senior line. “There are lots of different ways of providing flexibility to a borrower,” McLeish insists.

The fact that private debt managers may find themselves subordinated to bank lenders, either by tenor or in documentation, also has an impact on structuring. “To cover our risk, we want to make sure we are the first secured position,” says Paul Carman, founder and chief executive at Private Capital Group. “The assets [we invest in] are secured and the associated cash flows highly defensible.”

The common thread is identifying companies with reliable cash flows and then structuring a debt profile that meets them. “We are not fixated on getting money back in equal amortised repayments. Rather, repayments are based off a series of projections closely diligenced and stress tested to ensure their appropriateness,” Carman continues. “We want to make sure borrowers continue to pay their interest and that our funds are fully deployed.”

The trade-off for holding little-traded assets, Carman says, is the reassurance that the private debt originator has greater information throughout the life of the loan. “We are trading off reduced liquidity but we have much greater insight to the credit quality of a business. We spend significant time with management and owners during our due diligence process, which enables us to build an ongoing and direct relationship.”

Part of the task ahead involves explaining the New Zealand private debt opportunity to large international funds while also introducing the asset class to domestic investors. There is reason for the local market to pay attention. “New Zealand investors have typically been advocates of traditional 60:40 equity to fixed-income strategies and have historically been able to achieve their return targets through middle of the road, vanilla deployment,” Carman says. “This has come unstuck over the past 12 months as the OCR rose and markets dislocated.”

The issue for global funds may be scale. New Zealand’s business lending market is small and financiers based in the US or Europe wanting to deploy funds at scale are likely to have more readily accessible options. On the other hand, it is precisely the smaller end of the credit spectrum – businesses seeking to borrow NZ$5-30 million – that are most likely to be looking outside the bank space.

This too may be changing, however. The private funding route is attracting a wide cohort, McLeish insists, from relatively small businesses seeking NZ$5-10 million up to companies with hundreds of millions of dollars of funding requirements in different forms. “We are seeing quite a spread of borrowers looking for more flexibility,” McLeish confirms.