Australia's energy transition seeks higher fruit

Australia’s energy transition has accelerated. But it is not a straight-line journey to net zero and signs are that each progressive step brings new challenges. With the low-hanging fruit now mostly picked, martialling investment capital for equally vital future progress will be no easy task.

Kathryn Lee Senior Staff Writer KANGANEWS

The next three decades should see Australia progress to fully renewable energy generation. In this future, the sun takes the day shift while wind steps in to ensure the lights are on at night. When there is a shortfall, battery and other storage technology will be there to fill the gaps. This is no longer a dream or even an aspiration but a concrete target. What it is not – yet – is a fait accompli.

Australia has legislated targets to be net zero by 2050 and to have reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 43 per cent on 2005 levels by the end of the current decade. Tied into the 2030 target is an ambition to grow the renewables share of the National Electricity Market (NEM) to 82 per cent.

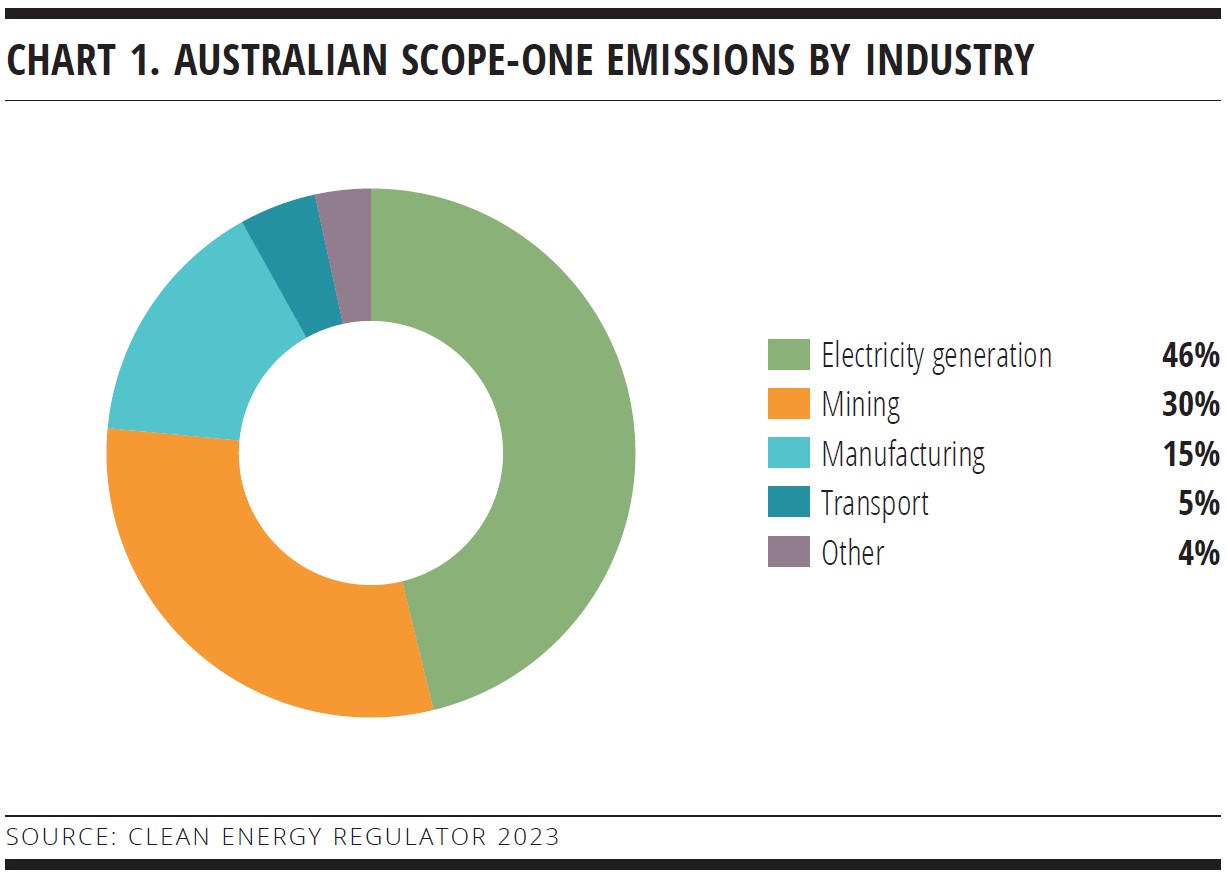

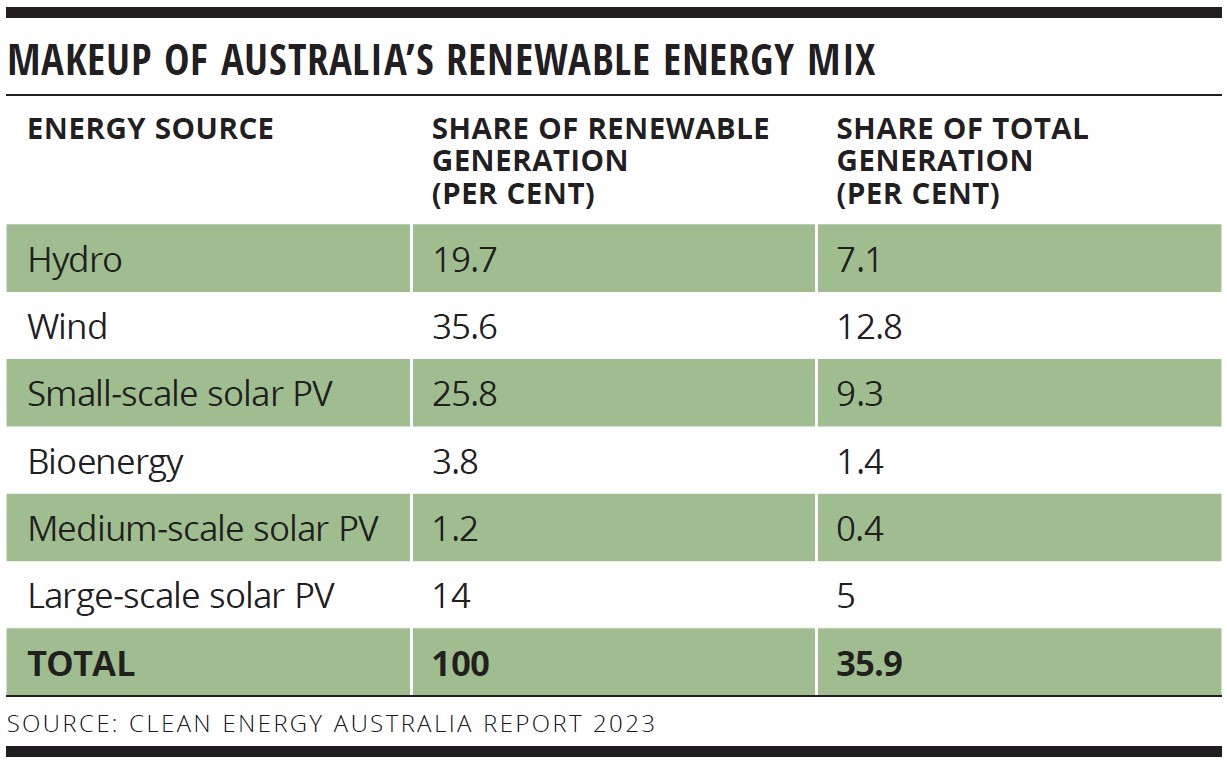

There is still a lot of work to do. As it stands, energy production is the largest contributor to Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions: according to the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) scheme it accounts for almost half Australia’s total scope-one emissions (see chart). Clean Energy Australia data show renewables account for just 35.9 per cent of Australia’s total electricity generation (see table).

Progress is being made. In the 2021/22 reporting year, NGER data note a 5 million tonne year-on-year reduction in scope-one emissions by the 946 corporations that report under the scheme – mainly due to increased use of renewables. Australia’s overall use of renewable energy has almost doubled in barely half a decade, from 16.9 per cent in 2017.

In the same vein, in April the International Energy Agency (IEA) released a review that commended Australia’s updated decarbonisation targets and noted renewable deployment had a positive outlook thanks to “the success of rooftop solar, ambitious targets, and increased funding at federal and state levels”.

Even so, analysts say hitting the 2030 renewable energy goal still looks challenging based on the trajectory of renewables use. The IEA paper highlights the significant transformation Australia’s electricity industry still needs to undergo. “Power sector decarbonisation efforts need to be stepped up considerably,”

it stated. “This will require an accelerated implementation of renewable energy zones, faster permitting of grid related projects and additional coal retirements.”

DIFFICULTY STEP-UP

At the Investor Group on Climate Change (IGCC) Summit in Sydney in August, Anna Freeman, policy director, decarbonisation at the Clean Energy Council (CEC) – a not-for-profit that represents Australia’s renewable energy industry – noted that Australia’s increase in renewable energy use since 2017 “deserves a round of applause”. But she has a degree of concern about future progress.

For one thing, the pace of renewables uptake may simply be slowing. There were no new financial commitments to large-scale renewable energy projects in the first quarter of 2023 and just four in Q2. According to a CEC report, investment in 2023 is 50 per cent below the rolling 12-month average and “a long way off the pace necessary for Australia to achieve an 82 per cent renewable energy share by 2030”. Freeman said this “shows that we are struggling” and attributed Australia’s investment slowdown to four primary causes.

The first is the significant shortfall of investment in transmission infrastructure. Australia’s electricity grid was built to handle one-way distribution from large generators to the end user – generally, from coal-fired power plants directly to customers. Now, however, many customers feed their own power into the electricity grid via rooftop solar panels. This is a fundamental change in the way the grid is used.

In addition, the location of wind and solar farms is usually different from fossil fuel power plants, meaning new infrastructure to transport power has to be built. Then there is the complication of the intermittent nature of renewables compared with conventional power. “Chronic underinvestment in grid capacity has led to congestion and constraints for where generation can be placed. This makes for a lengthy and complex process for projects to get online,” Freeman said.

It also introduces a “great deal of investor uncertainty”, she added. To commit what can be very substantial funds to a project, investors typically need to have a final letter from the operator confirming capacity to connect.

The Australian government’s A$20 billion (US$12.8 billion) commitment to improve grid infrastructure via its Rewiring the Nation programme will go some way to help. But it is not as simple as throwing money at the issue. Vivek Dhar, lead mining and energy commodities strategist at Commonwealth Bank

of Australia in Sydney, tells KangaNews the task is significant especially in some areas of the country.

Project developers in northwest Victoria, for instance, are at risk of significant curtailment of asset value because the network is not up to scratch for a change in the generation and distribution matrix. Dhar comments: “Getting everything right is a huge challenge. Coal is exiting but it is not a simple one-for-one substitution – the replacement is complicated.”

Historical context also plays a role. Dhar explains that grid infrastructure has been difficult to develop due to rules designed to prevent future ‘gold plating’. This is when the setup of a regulated profit system in the privatised network infrastructure sector gives power companies a perverse incentive to over-invest in infrastructure.

“The cost of a solar panel today is about a tenth of what it was 15 years ago – and it is very hard for a company to grow profits while prices fall by 90 per cent. The same dynamic will need to occur in hydrogen production, carbon capture and storage, and most of the other solutions required to decarbonise.”

Past gold-plating scandals led to an overhaul of the regulation – which, Dhar says, has now swung back the other way to the extent that power distributors find it hard to commit to building a grid suitable for a largely renewable generation mix. “The historical context is holding us back because the regulatory investment test for transmission is quite onerous and getting a project approved under this process is hard. There are good policymakers out there trying to quicken the process, but the challenge is to do so while also maintaining everyone’s best interests.”

In this context, social licence issues can also stand in the way of putting new infrastructure in place – such as getting permission from landowners to build new poles and wires. Dhar asks: “We need thousands of kilometres of poles and wires – but how do we bring everyone along on this journey?”

Freeman’s second key issue is rising project cost. Over the last five years, developers have contended with higher commodity prices, more expensive steel, and increased shipping and labour costs – to the extent that Freeman revealed that CEC members are reporting a 30-40 per cent increase in some project costs. There is a consequent marginal reduction in willingness to green-light developments.

The third issue is the difficulty of planning, including environmental processes hampering progress – so-called ‘green tape’. “In some states – and I will give an honourable mention to New South Wales – it is particularly difficult, complex and costly. In some jurisdictions it is actually becoming harder,” Freeman said at the IGCC conference.

Finally, Freeman noted the lack of a target or policy mechanism for the Clean Energy Regulator’s renewable energy target schemes, which have created a market to incentivise renewable energy generation via tradeable certificates but are due to end in 2030.

Tradeable certificates are registered by the regulator for every megawatt hour of power renewable generators of all sizes produce. Wholesale purchases of electricity then buy the certificates to meet renewable energy obligations. There is also a secondary market used by financial institutions, traders, agents and installers.

Freeman said: “Let’s say a developer makes a financial investment decision this year or next. This project might come online in 2025 or 2026. This means four years of certificates, which is not necessarily enough to be financially material to support an asset over a typical 25-year lifespan.”

Corporate power purchase agreements (PPAs) have partly filled the gap. These are a lasting agreement for a company to buy power from a renewable energy project for a fixed price over an extended period. For example, NBN Co announced a PPA in October this year under which it will purchase 90GW hours of electricity from the Macarthur Wind Farm in south-west Victoria. “Corporate PPAs are helping,” Freeman commented. “In fact, the voluntary market is driving investment decisions more than any mandatory mechanisms.”

Offshore wind prospects change direction

Offshore wind power generation is a burgeoning industry in Australia. For instance, in December 2022, the Australian government declared an area in the Bass Strait off Gippsland in Victoria to be suitable for offshore wind and followed with a similar announcement in July for an area in the Pacific Ocean off the Hunter region. David Murray, senior credit analyst at PM Capital, shares his views on the potential.

Onshore wind and solar started developing decades ago and are becoming mature industries with a clear value proposition. Offshore wind is a step behind in technology and cost.

The first offshore wind farm was built more than 20 years ago in Denmark. It was small and hardly made any power. It was a start, nonetheless, and from this point offshore wind gained popularity in other parts of Northern Europe and the UK.

Today, it has reached the point where Germany was able to run an unsubsidised offshore wind auction: market forces allowed offshore wind to make money on its own. This is an important milestone for any technology.

Germany subsidised the industry for years, gradually winding it down to the point where it can now host unsubsidised auctions with a lot of competition for offshore wind rights. To get to a similar position, Australia will absolutely need subsidies. It is not yet possible to start the industry without it. Offshore wind, as a technology, is initially expensive and needs the establishment of an entire supply chain.

Modern offshore wind blades are more than 100 metres long and don’t come in pieces that attach together – they come as giant single blades. For this reason, manufacturing everything in China or Europe then shipping it to Australia would be expensive and impractical, so generally it needs a local manufacturing supply chain. This carries the added benefit of creating a local industry that can eventually become an unsubsidised source of Australian energy.

There is a big outlay to establish a manufacturing base. This also means that the fifth wind farm, for example, becomes cheaper after the first four have been built. But the first is very expensive, which is where subsidies come in.

Europe and the UK are reaching that point of lower subsidies. Meanwhile, the US is investing lots of money into subsidies and supply chains, and should have a far more mature offshore wind market in five years. Australia is a step behind.

CAREFUL CAPITAL

There is also the issue of aligning capital with projects. Social need and even legislated targets do not necessarily align with investor preferences, yet the expectation is that private-sector capital will do much of the heavy lifting in Australian energy transition. The rates environment has thrown project economics for a loop.

David Murray, senior credit analyst at PM Capital in Sydney, explains: “There has been a painful shift away from the world of zero interest rates, no inflation, and flat construction and commodity costs – everything has become more expensive in the past two years. The economics of renewable projects look weaker, which is why we have focused our investments on companies that structure their business to accommodate these hurdles. There is a big clear-out going on.”

Scale is an important consideration – and this plays into the hands of global operators that tend to be far larger than Australian equivalents. For instance, Murray tells KangaNews US-based renewable energy developer, NextEra, is a good example of a business that has added resilience via scale. It started as a utility but added renewable generation capabilities – in effect, using regulated returns to build renewables in Florida. Eventually, this lowered the cost of power in the state and the company has now expanded into other part of the US.

Murray comments: “NextEra is an early mover, experienced and has massive scale. Each individual project in this sector is so chunky that companies need to be able to absorb issues without blowing up the business. NextEra’s projects are big but not make-or-break. They each add a little more value and there is always something developing.”

It can be harder to find equivalent opportunities in the Australian market. PM Capital therefore tends to make most of its renewable-oriented investments overseas. “Our Enhanced Yield Fund has very specific requirements and it can be hard to find an Australian renewables business that is actually investable,” Murray reveals. “Most are not listed, not bond issuers or conglomerates, or don’t meet our quality hurdles. I’m sure there are some great Australian businesses but they typically don’t meet these requirements and are therefore a more specialist investment proposition.”

Where there is scale in Australia, it tends to mean renewable assets being wrapped up in larger businesses. Murray cites APA Group as an example. He notes that while the company is developing renewables, and certainly has the right size profile, it does not line up as a specifically renewables investment.

“APA’s composition is mostly gas pipelines plus some solar and wind, so it isn’t the most efficient way to gain renewables exposure,” Murray tells KangaNews. “There are not many big, dominant companies in Australia for investors that want exposure to pure-play renewables. It may be different for banks and many funds but, for an investor like us that looks for best-in-class pure-play businesses, the offshore options are a long way ahead.”

Neither can investors assume they are going to ride an upward trajectory of renewables exposure within larger energy businesses. Tom King, Brisbane-based chief financial officer at Nanuk Asset Management – a global fund manager that considers a broad environmental sustainability and resource efficiency theme in its investments – says it is easy to compare the net zero transition to the internet boom and assume it will yield the next Apple, Microsoft and Google.

However, King argues that it is important to recognise the energy transition has a fundamentally different profile from the growth that happened in tech in the early 2000s. “The difference is that decarbonisation means a lot of heavy assets and the companies involved in these supply chains do not have the profound global network effects and low incremental costs we have seen in software and technology,” he explains. “Instead, they have large, capital-intensive operations that require a lot of working capital. To achieve emissions targets, solutions will have to be sold at cheaper and cheaper prices. This creates a very challenging investment dynamic.”

King points to the solar industry as an example. It has grown by a multiple of 50 in a decade and a half, but many businesses have failed and even those that have survived have rarely delivered good investment returns.

“The cost of a solar panel today is about a tenth of what it was 15 years ago – and it is very hard for a company to grow profits while prices fall by 90 per cent,” King comments. “The same dynamic will need to occur in hydrogen production, carbon capture and storage, and most of the other solutions required to decarbonise. Investing in these industries requires a careful and selective approach to avoid falling into a trap.”

The same pattern is emerging in other prominent technologies. King suggests that it has become obvious to the investor community that sectors like solar, batteries and electric vehicles have attracted huge amounts of capital in public markets and this has, in many cases, pushed valuations to a level that makes the risk-return profile significantly less attractive.

SEEKING INVESTABILITY

The energy transition will require a wave of investment capital. Investors say making the right calls requires them to have a clear view of how the next 30 years will play out and then to use this scenario to inform decisions. The challenge is that the low-hanging fruit has largely been picked and the next phase, while equally critical, does not have the same obvious alignment of interests.

King categorises the last 15 years as government and investors striving to implement “near perfect” solutions. In the near future, he expects a ramp up in support for all solutions that can decarbonise industries.

He says: “We know where emissions are coming from and we have done so for a long time. To get to net zero we must either eliminate or offset these emissions and the government will need to legislate for this to occur. But we are not going to get where we need to by insisting that everything is done ‘perfectly’.”

This means the decarbonisation of the electricity sector, oil and gas, and industry more broadly – as a big proportion of emissions comes from processes like the production of steel, cement and plastics. Then there is the decarbonisation of transport. The good news, King continues, is that in most cases the technology solutions “are already clear”. It is just a matter of how and when progress happens.

In practice, this means King sees opportunities in ancillary areas such as the electrification of buildings, heavy transport – including air transport and shipping – and grid technology. “These are areas that require significant capital but have not become investment trends in the same way as electric vehicles or renewables. This means they present a more interesting opportunity,” he says.

Meanwhile, Murray is excited about the burgeoning opportunity presented by offshore wind (see box on facing page) on the basis of his belief that, ultimately, solar and wind will be able to meet most of Australia’s electricity needs with future improvements in storage filling demand gaps.

The technology lag means the transition fuel argument has some validity, Murray says. “There is a general dislike for fossil fuels but, realistically, gas demand is increasing. There is a lot of money to be made by carefully investing in these areas. A realistic transition can’t just be a full, immediate switch to renewables – we need to get there in a way that doesn’t put too much cost or unreliability on consumers,” he comments.

“Gas isn’t clean – but it is cleaner than coal and better at filling in the gaps left by intermittent renewables,” Murray adds. “It would be idealistic to deny that the transition requires something else to complement renewables while clean storage options improve. Gas fits this gap much better than coal. There is a good case that it is the most responsible option.”

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.