Home is where the heart is

Australian fund managers confirm that international pricing levels play a role in determining their appetite for domestic primary-market deals – even if they do not participate in offshore bond markets. However, other considerations are also important and local investors insist they are working hard to keep their home market relevant.

Helen Craig Deputy Editor KANGANEWS

During a challenging year for Australian corporate bond issuance in 2016, one of the many factors blamed for the sluggish market was local investors’ apparent insistence on being compensated at least in line with issuers’ global curves. Australia, it seems, is not keen to give a home-market discount.

Relativity to offshore spreads is important. But so are liquidity, diversification, specific mandate restrictions, and terms and conditions. What shines through most clearly when talking about market dynamics with investors is the depth of thought they put into questions like how to keep the domestic capital markets relevant. While investing offshore is an option for some, all say they are working hard towards a common goal of ensuring their home market remains a viable option.

We have a duty of care to our clients to transact in the most appropriate manner and to take the best opportunities. If transactions are not priced attractively or if the terms and conditions in the bond documentation do not provide the appropriate protection for our clients we will not participate.

Primary levels

Few market participants would argue with the suggestion that 2016 was not a banner year for the Australian corporate market. Issuance was low, and while this was in large part the consequence of of a skinny funding task in corporate Australia even the deals that came to market did not always meet an avalanche of demand.

For example, in October last year APA Group (APA) printed A$200 million (US$153.5 million) in its first domestic deal since 2010. The seven-year transaction was sized to demand and priced in line with minimum-volume expectations and initial price guidance of 180 basis points over semi-quarterly swap.

This outcome fell short of the same issuer’s domestic debut, six years prior. The 2010 deal was bigger – at A$300 million – despite having 10-year duration. The word on the street following APA’s 2016 pricing was that domestic investors were unimpressed by the margin offered. The consensus seemed to be that the pricing target for the new issue was out of synch with comparable price points on APA’s global curve.

Several sources close to the transaction told KangaNews they believed the final book could have been larger but for an inability to reach agreement on implied fair-value levels in APA’s bonds. APA has a range of US 144A-format bonds outstanding, including US$735 million of bonds due to mature in October 2022. These were indicated at the equivalent of 240-250 basis points over Australian swap in October last year, at the time of the latest domestic deal, according to market sources.

At the time, several investors said the extra margin offered in the offshore secondary curve made it difficult to participate in the domestic deal. While APA is often cited by domestic investors as a classic example of a transaction offered domestically well inside an issuer’s established global curve, fund managers say the phenomenon is far from unique.

More promisingly, it seems issuers that come to the Australian market targeting a price investors consider to be fair value relative to their global curve can still get very good outcomes. For instance, AusNet Services Holdings (AusNet) accumulated a final book of A$800 million for its A$425 million, 10.5-year domestic deal priced on 7 February this year. Contrary to some expectations of an Asian-investor-dominated book, domestic investors took 58 per cent of the paper according to data from the arrangers.

In the wake of this transaction, lead managers told KangaNews that solid take-up from domestic fund managers was at least partly attributable to the fact that the bonds priced in line with AusNet’s global curve. It seems, then, that domestic investors rewarded AusNet for not trying to extract a substantial discount from its home market.

Offshore comparison

Fund managers universally report that global price comparison is an element of their decision-making process when studying new issuance domestically. But it is far from the only consideration.

While declining to discuss specific transactions, Tim van Klaveren, managing director and senior portfolio manager at UBS Asset Management in Sydney, says: “There are a few reasons we wouldn’t buy a domestic deal if the pricing is very different from global levels. One is relative value – if the market has priced a credit globally there’s no reason we would want to buy a new domestic issue well inside that price. Also, there’s a risk you get a negative mark, and the local market could reprice to where the global curve is.”

Adrian David, Macquarie Investment Management (Macquarie)’s Sydney-based head of credit research, echoes this view. “We will look at any bond that comes to market on a relative-value basis and where this bond is offered relative to its global curve,” he tells KangaNews.

Comparing domestic primary with offshore secondary is clearly an established practice. However, it is also widely understood that Australian investment managers tend to make a greater proportion of their allocations via primary transactions. Primary-market issuance has been the major point of liquidity for local investors because the risk of participating tends to be compensated for via a new-issue premium. Perhaps more significantly, investors acknowledge that primary deals are often the only way of reliably securing relatively large parcels of securities.

Looking at offshore pricing is one thing, but whether or not investors can or will actually buy an Australian issuer’s foreign-currency bond – often several years after it came to market – is another matter. For example, David suggests that while Macquarie can buy offshore bonds, doing so is a complicated consideration.

“We manage a wide variety of funds with different return hurdles, risk tolerances and mandates. The more risk taking that is permitted within these funds, the higher their return targets are and the more capacity they have to pursue credit opportunities anywhere. But it is less likely we would chase an issuer offshore for a low-risk fund that might have a single-A threshold,” David explains.

However, he also insists that secondary marks in global core markets are both credible and executable. “We have credit traders based in Europe, the US and Australasia. The levels we see are sourced from broker runs so they are the levels at which we believe we can execute.”

Other investors acknowledge that the ability to acquire a primary-market-sized allocation of bonds at close to rate-card levels is far from a given. It is most appropriate to make genuinely tradeable comparisons if the relevant offshore bond is a large, liquid line from a frequent issuer.

“It is generally easier to execute in well-known bank names with large issue sizes in US dollars and euros rather than in other parts of the market and in other currencies,” Michael Bors, senior portfolio manager at Challenger Investment Partners in Sydney, tells KangaNews. “But even then, the ability to transact in size at the offer level is questionable and highly dependent on market conditions at the time.”

Bringing in the basis

By the time hedging costs and the implications of having foreign-currency investments as part of an investor’s overall risk profile have been factored in, buying an offshore bond is far from a straightforward choice.

In the first instance, investors point out that in buying offshore assets they are exposed not only to global credit spreads but also to cross-currency basis-swap spreads.

“This is fine for a hold-to-maturity investor but we look to turn stock over and pick up the roll effect from a steeper curve,” George Bishay, portfolio manager at BT Investment Management, tells KangaNews. “Volatility in cross-currency basis-swap spreads must also be taken into account when investing in offshore assets.”

George Bishay, portfolio manager at BT Investment Management, explains: “Banks limit how much volume they have in any specific line. If I am looking to buy corporate securities in secondary I have to chip away with different counterparties to execute my position size. It is difficult for me to buy the size that I want in secondary – and this is where primary becomes more valuable.”

Another impediment to buying offshore bonds is the additional price tag from the fact that while secondary marks can be relatively easily swapped back to Australian dollar levels they do not account for swap transaction costs (see box).

The most telling point, however, is that fund managers say they do not actually need to expect to acquire significant parcels of bonds offshore for the domestic primary-offshore secondary comparison to be relevant. In fact, even Australian investors that are precluded from buying offshore bonds look at international levels when assessing pricing on domestic deals.

“We deal predominantly in the local physical space,” says Bishay. “Ultimately, though, when a new issuer comes to market we first look at the local curve, followed by an offshore comparison of the specific name and how it swaps back to Australian dollars. We also look at other names within the sector – both locally and offshore – and at where they swap back.”

Van Klaveren adds: “We have a duty of care to our clients to transact in the most appropriate manner and to take the best opportunities. If transactions are not priced attractively or if the terms and conditions in the bond documentation do not provide the appropriate protection for our clients we will not participate in any new issue, or even buy the bonds subsequently in the secondary market. Tight pricing and unfavourable terms and conditions will affect the volume of bids, if any, that investors will put in for new deals.”

Offshore mark accuracy

One factor mentioned by several investors as a reason for looking at offshore secondary spreads – even if they do not expect to execute – is that offshore marks are more accurate than Australian rate sheets. Investors say the accuracy of secondary marks largely depends on the bond in question, as well as the sector and the volume they want to trade. Regarding the local market, the quality and reliability of rate-sheet marks mostly depends on the issuance backdrop.

“In good times, local marks are largely accurate because the market is relatively liquid during these periods,” says Phil Strano, senior portfolio manager, credit at Victorian Funds Management Corporation in Melbourne. “During risk-off periods marks become stale quickly and take a long time to readjust. Because the offshore market is far deeper, with more active buyers and sellers, a risk-off environment doesn’t appear to affect secondary-trading ability in the same way.”

David agrees: “Secondary marks offshore are slightly more reliable than they are domestically. You just get deeper liquidity offshore.”

With no equivalent of the US Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) to record and disseminate trade-volume data, there is little readily available information on how frequently corporate bonds change hands in Australia or in what volume. Investors suspect many rate-sheet marks are not based on actual clearing prices as there may be little or no trading activity in many lines.

“The difficulty comes when marks are put on corporate lines that are not owned or traded,” Bishay argues. “Marks and prices gel in many cases, but it is only when a new deal comes to the primary market that there is true price and volume transparency. Even though an issuer may have traded in small size in secondary at wider spreads, demand for a new primary deal could be huge, tightening spreads for that issuer, and its sector, accordingly.”

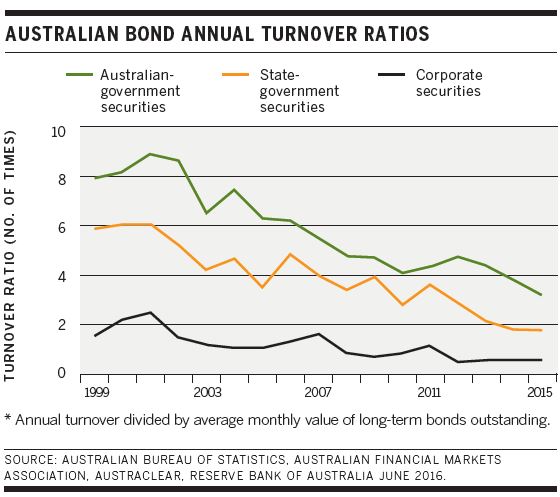

Another reason investors have developed an increased reliance on offshore secondary pricing marks is that local secondary volumes have plunged. The extent to which local banks’ balance sheets are constrained in their ability to hold, and therefore turn over, less liquid paper means that local secondary-trading volumes across all asset classes have plummeted.

According to official data, turnover in all Australian securities has fallen since the turn of the decade and nonfinancial corporate security turnover is minimal (see chart). This environment is forcing changes to sales and trading capability for banks and their clients. All parties are gradually acclimatising to the demands of the new world (see box).

Fund managers move with the times

Australian fund managers say they are becoming more nimble in response to lack of liquidity in the local corporate sector. Supporting investors’ needs requires a flexible approach in the intermediary space, too.

Global outreach is a high-ranking factor in keeping the Australian market relevant and maximising its liquidity. This means both international investor participation at the primary stage and the ability to maximise secondary bid and offer capacity via global distribution.

In one of the more surprising KangaNews Awards results in recent times, Citi rode the strong support of Australian fund managers to be acknowledged as Australian Dollar Credit House of the Year – Secondary Market in 2016. Since 2010, this award and its historical equivalents have been dominated by Australian major banks and their larger local balance sheets.

We are seeing more local fund managers ensuring they have the right people on the ground to carry out their credit work via the right processes, even if this is in a time zone beyond their normal operating hours.

More than price

Local investors’ preferences for local or offshore bonds is not based purely on a pricing play, either. Domestic buy-side sources tell KangaNews they consider a range of other factors in their decision-making processes. These include liquidity, diversification, mandate dictates and whether they are being truly compensated for a bond’s terms and conditions.

A predictable and acceptable level of liquidity is key. Van Klaveren comments: “What many issuers do not understand is that the more liquid the bond the more likely it is than an investor will want to own it – including potentially being willing to pay a tighter price for it. The less liquid the bond the greater the new-issue premium investors will charge.”

He adds: “When we price a new issue we factor in a liquidity premium. Issuers need to understand that they pay for what they get. If they pay a tight fee for originating a new deal they are only paying the originating banks to place their bonds and they may get no price support in the secondary market.”

Terms and conditions are also top of investors’ minds when they think about the validity of the domestic bond market. At least one investor tells KangaNews that unfavourable terms and conditions relating to an early call date and change of control in the latest domestic deal from APA also contributed to the lack of enthusiasm the deal received.

Talk of call options brings to mind the issue last year when Scentre Group (Scentre) exercised an early call option on A$900 million of Westfield Retail Trust bonds. In doing so, Scentre par-called bonds that were marked at a premium. There is no suggestion that the issuer did anything it was not fully entitled to do, but local institutional investors admit that the fact the par-call is not a standard feature of the Australian market meant many were surprised by the decision to exercise the clause.

Investors have since walked the walk when it comes to voicing concern about terms and conditions. KangaNews understands that late last year a meeting was held between 27 of Australia’s largest fund managers and syndicate representatives of the four major banks, to discuss local-market development. Terms and conditions were high on the agenda and fund managers put forward the aspects of bond documentation that were desirable to them in forthcoming primary transactions.

“Recent bond deals have included terms and conditions that are not in investors’ best interests,” van Klaveren says. “Investors are happy to price new issues with different terms and conditions included, but we need to be compensated for these differences – especially if we are being asked to sell or offer optionality.”

He continues: “If new issues are being priced tightly and investors are also not being compensated for variation in the terms and conditions in the documentation, there is no incentive for investors to participate in these deals.”

Offshore drift

The fear for the Australian market is that offshoring funds becomes the more straightforward option even with the acknowledged hurdles and risks it bears. One investor with access to in-house portfolio managers from the firm’s offshore operations implies it is easy to allocate into a specialised credit portfolio or a global fund via its offshore branch.

“It’s very simple,” the fund manager says. “They can invest in primary or secondary and we hedge back into Australian dollars. The next move could be shifting all our money offshore which would of course be very detrimental to the local market. End investors that want to invest offshore might even just decide to put all their funds directly with an offshore asset manager, effectively cutting out the middle person.”

What fund managers expect to occur over time is greater differentiation of pricing between more and less liquid bonds. Bors insists that liquidity in a sustainable sense comes from a change in market structure – something he argues is already beginning to occur. “We need a diverse range of participants with differing strategies and mandates. In recent years the local market has been a beneficiary of a more diverse structure, owing mainly to greater participation by offshore investors.”