Sustainable finance targets transition

Transition is regarded by many as the holy grail of sustainable finance, achieving the greatest impact for the investment dollar by supporting the change economies need to achieve carbon-reduction targets. Market participants are wrestling with the challenges of developing a transition-finance market that is both attractive to new entrants and sufficiently rigorous.

Chris Rich Staff Writer KANGANEWS

Kathryn Lee Staff Writer KANGANEWS

Transition finance stood out as a dominant theme at the week-long 2021 Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) virtual conference in early September. Participants discussed the need for a more granular approach to decision-making processes if a 1.5 degree world is to be realised.

The evolution of the green-bond market over the years has seen the proliferation of use-of-proceeds (UOP) bonds. As discussion in financial markets has turned to the role of capital in the transition to a net-zero emissions future, debt-market participants are reassessing the role UOP bonds will play in this transition – or are at least asking whether debt finance can do more than simply refinance existing green and social assets.

This has been thrown into sharper focus with the rise of sustainability-linked loans and sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs), which tie KPIs to the cost of financing arrangements. As forward-looking instruments, they arguably generate greater impact – at least when ambitious emissions-reduction targets are included in the metrics – compared with UOP bonds.

The market may already be developing in such a way that the issues solved by UOP bonds are no longer investors’ primary focus. As global investors increasingly set up portfolios to be consistent with a 1.5 degree future, company-wide transition pathways are becoming as or more important than the instrument-level credentials of green and other UOP bonds.

Transition may simply become a standard component of credit analysis based on the risk to businesses of not aligning with the future economy. Borrowers – corporate, financial and public sector – that do not have a plan to align themselves with a 1.5 degree world, in a suitable timeframe, will find it increasingly difficult to access finance, market users believe.

This view chimes with recent findings in the Australian investment market, which seem to suggest ever-greater integration of sustainability practice across the board (see box).

GRANULAR APPROACH

Excluding fossil-fuel companies that will not survive the transition to a net-zero economy from portfolios is standard practice for many investors. But the buy side is also increasingly thinking about capital allocation through the transition and where the opportunities lie.

Speaking at the CBI conference, Anders Schelde, chief investment officer at Danish pension fund, AkademikerPension, said green bonds are an important component of this. But managing investments as the economic transition progresses requires a view on whether companies are moving fast enough. “It needs to be addressed, as we did, by setting targets to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions in the portfolio and making sure the targets are aligned with those in the Paris Agreement,” he said. “It should not just to be net zero by 2050 but also interim targets.”

AkademikerPension has a 2025 emissions-reduction target of 27 per cent to stay on the path of the Paris Agreement. “This means big emitters need to do something – and we are in dialogue with them,” Schelde added.

Nathan Fabian, chief responsible investment officer at Principles for Responsible Investment, emphasised the same point. After years of focusing on environmental risk as a problem for the future, he said the market needs to be more specific and granular on how the environmental performance of activities is supporting effective transition.

Fabian pointed to the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) as a bellwether for the market. “Companies are increasingly aware they should be disclosing to investors using a framework like TCFD to indicate they understand the problems of climate and transition,” he said.

But even as jurisdictions make their first steps in mandatory TCFD reporting, Fabian noted it is vital to continue striving for more. Reporting against TCFD allows investors to see that companies have governance structures in place to address the problem from the top down, and a plan to monitor progress. However, Fabian added: “This is well and good but I think we are now realising we also need something else. Investors need to ask whether the plan is credible relative to the environmental context and goals.”

As well as setting net-zero targets, emerging coalitions like the UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance and the Net-Zero Asset Managers Initiative are thinking about the proportion of portfolios that needs to be goal-aligned today, in 2025 and 2030. Fabian said this is the level of granularity needed.

The development is not lost on borrowers. Samantha Sutcliffe, head of green and sustainable finance at UBS, said: “We think of green bonds often in terms of the use of proceeds. But when we actually work with companies to help them set up the governance behind their framework and green programmes, we really see how the process is affecting whole institutions in a positive way.”

The key part that can get lost when market participants talk about the impact of green bonds, Sutcliffe continued, is the way sustainable finance – even the supposedly limited scope of UOP bonds – can increase an organisation’s agility when it comes to driving an internal sustainability agenda.

In the surge to align with net-zero pathways, a plethora of guidance and standards has emerged to ensure the veracity of transition. Though many organisations use the same knowledge base – such as the Science Based Targets initiative, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and International Energy Agency – sector- and metric-specific initiatives are carving out directions to cater for the granularity demanded by stakeholders.

“Transition is going to affect every person and every market player, and they all have different needs,” Esther Stoakes, senior manager, assessing low-carbon transition at Carbon Disclosure Project, told conference delegates. “It is right that we have initiatives that are responding to these different needs within the market as a whole.”

This gets to the crux of the challenges inherent to transition finance. A complicated area of finance is arguably becoming even more so thanks to the variety of methodologies and metrics for benchmarking. At the same time, a heterogenous market gives rise to the perception of, or even the potential for, a greater blanket for greenwashing under which to operate.

The organisations and initiatives responsible for providing standards are alive to this issue and are working with one another to find commonality where they can, Stoakes explained. “We want to establish common language between companies and investors so companies can demonstrate credibility. Alignment is a real concern, but organisations talk and refer to each other’s work.”

Stoakes added that transition guidance is often playing catch-up with market expectations and demands. “We are seeking to update our standards, initiatives and outputs as fast as we can, but the field is moving very rapidly. This can be a point of difference at times.”

TRANSFORMING COMPANIES

Discussions at the CBI event frequently returned to the central goal of ensuring finance is extended to companies that are committed to aligning themselves to a 1.5 degree world in an ambitious timeframe. It is in this context that CBI launched a new discussion paper called Transition finance for transforming companies.

The paper highlights growing opportunities for companies to access finance for transition and presents a framework to assess the credibility of transition on a forward-looking basis, including CBI proposing to certify instruments beyond UOP bonds.

Launching the paper at the conference, Sean Kidney, CBI’s chief executive, said the sustainable-finance market is yet to tackle high-carbon transition areas adequately. “We need to understand what is rigorous and what the investments are that will make the change,” he explained.

The paper focuses on this area of transition finance, with the intention to provide transparency to science-based criteria for credible SLBs and similar instruments, and assurance for investors that these requirements have been met in respect of any certified issuance. CBI is also considering company-level certification.

The paper presents five hallmarks of credible transition, defined as one that is rapid and robust enough to align with the global goal to nearly halve emissions by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050, in line with the Paris Agreement.

The hallmarks are Paris-aligned targets, robust plans, implementation action, internal monitoring and external reporting. They address the requisite ambition of company-level targets and demonstrate willingness and ability to deliver on forward-looking goals, the paper says.

Australian responsible investment assets surge in 2020

A report published on 1 September by Responsible Investment Association Australasia shows responsible investment growth continues. Improving accountability among investment managers may be key to market development.

The Responsible Investment Association Australasia (RIAA)’s Responsible Investment Benchmark Report Australia 2021 says there was A$1.3 trillion (US$951.1 billion) of responsible assets under management (AUM) across asset classes in Australia by the end of 2020, up from A$983 billion the previous year. Moreover, the proportion of responsible investment AUM to total managed funds grew to 40 per cent in 2020, from 31 per cent in 2019. Data for the report came from 198 investment managers, 59 of which provided survey responses.

The proposal aims to complement existing environmental, social and governance (ESG) frameworks while taking specific fixed-income instruments into consideration. “The intent is to bridge the gap between existing market guidance that is tailored specifically to SLBs and has good take-up but is lighter touch in detail – such as ICMA [International Capital Market Association]’s Sustainability Linked Bond Principles – and the deeper company-level assessment frameworks – that are more comprehensive but perhaps too complex for wide market take up,” the paper says.

One of the paper’s authors, Anna Creed, associate director, thought leadership at CBI, explained the framework aims to capture companies at various stages. “We do not want to leave those that have not started transitioning yet out in the cold. What we are proposing in our paper is two shades of transition.”

CBI is proposing that transition certification be broken into three categories. Green companies are already at net zero. Green transition ones are on a common sectoral transition pathway that aligns with net zero. Finally, interim transition companies are working toward the common sectoral pathway.

Importantly, CBI suggests that the third category would have a time-limited window – for instance to be in line with the common sectoral pathway by 2025 – to ensure credibility, Creed said.

Marisa Drew, chief sustainability officer and global head of sustainability strategy at Credit Suisse, said breaking transition down into subcategories should assist investors’ decision-making process beyond the current minefield of navigating strategies across the transition spectrum and assessing their individual credibility. “In concept, if we are going to get capital to flow in the scale we need, precision will help and will also bring in companies that are more hesitant,” Drew said.

MAINSTREAMING SUSTAINABILITY

While financing credible transition may be the main forward-looking goal, CBI conference participants were also keen to note the role played by UOP bonds, the spectacular growth of this market and how the product can be refined to continue delivering investment impact.

Combined issuance of green, social and sustainability (GSS) bonds, SLBs and transition-labelled bonds reached almost US$500 billion in the first half of 2021 – a 59 per cent year-on-year jump – according to CBI data.

While it took cumulative green-bond issuance 13 years to reach US$1 trillion after European Investment Bank issued the world’s first green bond in 2007, it may reach its second trillion by the end of 2021. CBI data forecast that, even with relatively modest growth, annual issuance of green bonds could reach US$1 trillion in 2023.

Increasing demand from asset managers is among the many factors to have influenced market growth. Speaking at the CBI event, Phillip Brown, managing director, capital markets at Citi, said climate discussions have been mainstreamed onto the corporate boardroom agenda and are now a feature of every client discussion. “Everyone recognises the significance of sustainability to corporate strategy, and this is why we have cause for optimism,” he said.

While Europe is widely regarded as the epicentre of sustainable finance, growth is now clearly a global phenomenon. This includes the US, which was until recently clearly a laggard. Lisa Bozzelli, senior director at Multifamily Capital Markets, said the North American GSS bond market is on an upswing though education continues to be a key focus for participants.

“A lot of stakeholders are coming up the learning curve, trying to understand what has been done and what can be done,” she explained. Bozzelli said she has seen a dramatic uptick in interest in the market, including an increase in prominence of climate-related risk assessment in investor portfolios. She believes the US re-entering the Paris Agreement has helped focus attention and said the timing and degree of regulatory change is a key factor to watch.

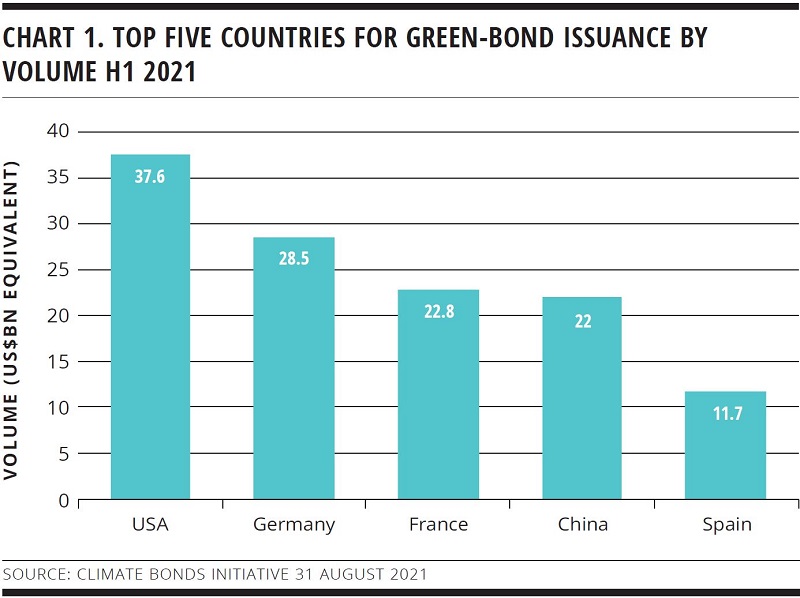

The Asia-Pacific region is also making progress, according to Sean Chang, head of fixed income at Ping An of China Asset Management. Chang said Chinese government policies and initiatives are the main motivator of investor appetite for green bonds at present. CBI data show the Chinese market was responsible for the fourth-largest issuance volume of pure green bonds in the first half of 2021, with the US, Germany, France and Spain making up the remainder of the top five (see chart 1).

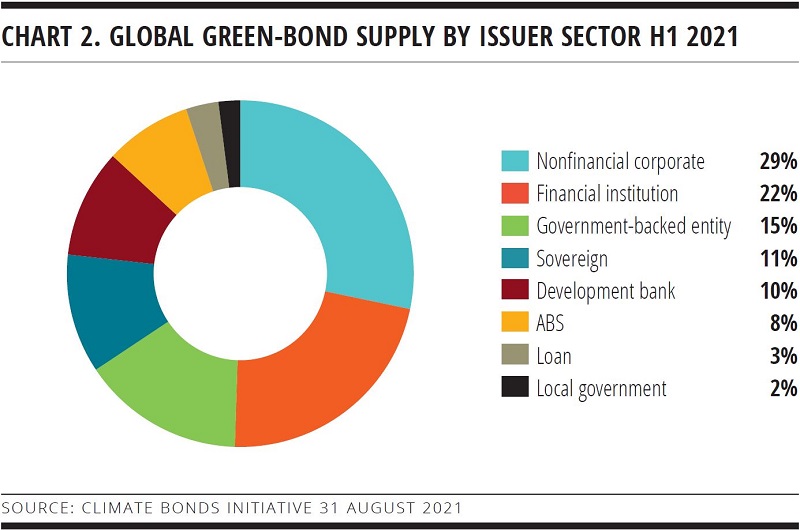

There is still potential for UOP green-bond growth. According to CBI data, sovereigns represented just 11 per cent of green-bond issuance in the first half of 2021 (see chart 2) despite making up approximately 55 per cent of total bond issuance.

Stephen Yeats, head of UK investments and global head of fixed income beta solutions at State Street Global Advisors, said it is critical for sustainable finance to be accessible in all segments of the market, especially given sovereign debt is clearly the largest component of global fixed-income allocations. “The market needs to be rich and diverse to ensure it can provide the sectors investors need for their asset allocation,” he said.

Increased green-bond issuance from sovereigns could have a dramatic effect on the future development of the market. In 2019, the Netherlands was the first triple-A rated country to issue a green bond. Elvira Eurlings, agent at the Dutch ministry of finance, was involved in structuring the bond and noted the positive flow-on effects of the transaction.

“At the time, there were only a few countries in the green-bond space,” she said. “Even so, when I went on the green-bond roadshow fund managers told me that when sovereigns became active in the green-bond space, investors started raising for impact funds. These allowed them to diversify their portfolios and made more climate-related financing available.”

Eurlings encouraged all governments that have not considered green-bond issuance to do so, adding: “I truly believe sovereigns are catalysts for the green-bond capital market.”

TRANSPARENT HARMONY

It is not just the emerging transition-finance market that is dealing with challenges associated with impact measurement and reporting. Lack of standardisation and access to data are also a hurdle in the UOP market – in fact, some believe they may be preventing investor allocations fulfilling their potential.

“ESG strategies and conversations about delivering more sustainable portfolios are becoming mainstream, but how to balance the cost, the risk and the liquidity – these are the thorny issues we need to tackle,” Yeats said. “The good news is there is genuine desire to solve this. We need to continue to push hard as an industry to solve some of these frictions.”

Just like the transition space, part of the issue is not a lack of reporting but variation in issuer disclosure, as reflected in the results of CBI’s May report, Post-issuance reporting in the green bond market. During the conference, Miguel Almeida, research manager at CBI and lead author of the report, discussed its findings, ultimately flagging various avenues toward increased standardisation as the solution.

“It is very rare for issuers not to report, but very few did so in the 15 months we allowed from the end of the cut-off date,” Almeida said – though he added that larger issuers tend to be more likely to report in a timely way.

CBI also found there was too much variation in the quality of reporting between issuers. While the metrics used in the report’s analysis scored many issuers highly, there was still a large disparity between the top and bottom scores.

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.