A job half done?

The dawn of 2023 came accompanied by a welcome return of positive sentiment in the fixed-income and credit markets after a fairly sobering year for bond investors among others. One cannot help but wonder whether confidence about rates direction and economic outcomes is at least somewhat overcooked.

Laurence Davison Head of Content KANGANEWS

Elsewhere in this edition of KangaNews you will read about the tremendous wave of new-issuance opportunities borrowers exploited at the start of 2023. The two sectors that traditionally highlight new-year issuance in Australia – bank supply at home and abroad, and inbound primary activity from the global supranational, sovereign and agency (SSA) sector – have both got off to roaring starts.

One quirky statistic showcases the positive tone. SSA Kangaroo issuance passed the A$10 billion (US$6.3 billion) mark for the year to date by mid-February – fully a month before any year in recent memory – even as the Japanese investors that have underwritten the sector for years turn, at the margin, away from foreign currency allocations. I asked one syndicate banker to give the highlights of where SSA demand has been coming from, and the response was straightforward: “everywhere”.

It has been the same story in early-year deals in the domestic credit space – which, ahead of corporate reporting season in February-March, means bank issuance. The big-four banks hit global markets for large benchmarks across asset classes – covered bonds, senior-unsecured and tier-two – but also found a welcoming investor base in Australian dollars.

Commonwealth Bank of Australia’s A$5 billion senior print on 9 January was the largest-ever Australian dollar credit deal. Six of the eight such transactions of A$4 billion or more printed last year, suggesting system growth in Australian dollar credit that near-term market conditions are doing nothing to stem.

While secondary-market conditions were starting to dial back the exuberance level by late February – market commentary was starting to hint at two-way flow rather than an ongoing bid – this had yet to dent the ability to complete new issuance.

The major banks had likely sated their near-term appetite but the nonbank securitisation market started to fire in mid-February. Three of the market’s biggest issuers – Columbus Capital, Liberty Financial and Pepper Money – came to market with new residential mortgage-backed securities transactions in the space of barely 24 hours, all achieving upsizes and eventual A$1 billion prints.

There are also signs of a thawing in the true corporate market. There is no denying that 2022 was a truly dismal year for Australian-origin corporate issuance, at home and abroad. Perhaps predictably, corporate treasurers seem more inclined to give offshore options a pass than their domestic market: there is, once again, talk of the Australian dollar market not being “there for” borrowers while at the same time the reliability of US private placement investors is not in doubt.

But the general feeling seems to be that corporate deal flow will return in Australian dollars once reporting season has passed and an issuer or two successfully takes the leap of faith necessary to demonstrate pricing and liquidity support. The key, as ever, is likely to be tenor: if Australian dollar investors move relatively swiftly to supporting corporate deals of seven and, ideally, 10 years there is every reason to think issuance volume will rebound fairly hard.

RATES DIRECTION

The positive new-issuance environment, however, seems to rest more than anything on one key fundamental: that the developed world, including Australia, is – to use perhaps the primary mantra of the new year – “approaching clarity on terminal rates”.

Even the formulation of this phrase, however, hints at an underlying uncertainty. Note that no-one believes we are at the terminal point; indeed, every analyst, trader and investor assumes there are multiple rate hikes still to come and most of them believe the risk is to the up side.

Instead, the upbeat tone seems to rest on two related factors. The first is that, while interest rates undoubtedly have some way to go, the bulk of the heavy lifting was done by central banks in 2022. Indeed, market pricing now suggests policymakers may be more likely to return to an easing trajectory by the end of 2023 than hiking throughout.

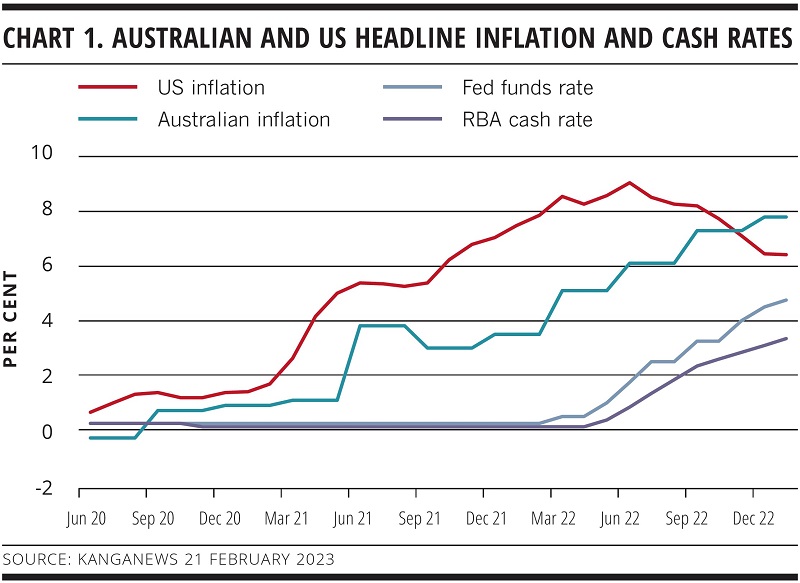

This projection certainly seems to mesh with what is happening with inflation in the US. Having apparently peaked at more than 9 per cent in mid-2022, US headline inflation has been falling ever since and dropped below 6.5 per cent by the end of last year (see chart 1). While the Federal Reserve’s aggressive hiking path – and, if anything, even more hawkish rhetoric – never got the Fed funds rate within hollering distance of inflation on an outright basis, it appears at this stage that the central bank did enough to stop inflation spiralling out of control.

What I find particularly interesting in this context is the divergence between US and Australian policy and inflation outcomes. The Fed started earlier and has remained more aggressive than the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), and the latter is now 1.25 per cent behind its US peer’s hiking path. Critically, while the rate at which Australian headline inflation increased slowed to 0.5 per cent between Q3 and Q4 last year, CPI has yet to start actually falling.

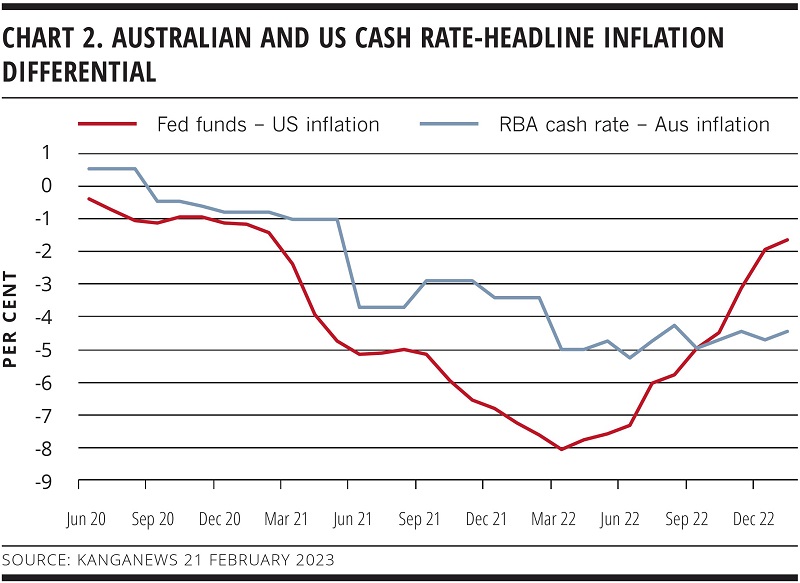

While the Fed funds rate has never overtaken inflation it has at least closed the gap. The RBA cash rate has been more than 4 per cent lower than CPI since March 2022 (see chart 2).

It now seems unlikely that Australian inflation will spiral out of control in a scenario where the RBA – as expected – adds a clutch more 25 basis pointshikes in H1 2023. However, if the Q1inflation print does not register a relativelysignificant drop one would have to startwondering whether such a benign pathwill be sufficient to start the process ofbringing inflation down to the targetband.

It seems to be an article of faith that Australian inflation will follow the US into reverse without the RBA stepping up its assault. I am not sure whether this faith will be justified – there are certainly signs that some inputs will push in the opposite direction to the RBA’s tightening tone.

Some analysts are predicting the iron ore price is on its way back up to US$150/tonne, for instance – a level it has only reached twice, and only once for more than a few weeks, in the past decade. Australia also seems to be winning the battle to attract migrants, which is no doubt a long-term positive but in 2023 will add pressure to the housing market and rejuvenate sectors like tourism and education after their pandemic challenges.

REVISION THING

I am never particularly keen to set out a stall in opposition to market consensus, on the basis that said consensus is typically the synthesis of the views of lots of people all of whom understand these things better than I do. On the other hand, I am hearing more muttering about whether it is really plausible that all the economic issues of recent years can be fixed with 18 months of rate hikes and a – relatively – shallow recession or even a soft-landing economic downturn.

This said, it is also true that a wave of inflation caused almost exclusively by external factors might not require the same radical corrective approach as a baked in domestic wage-price spiral.

Let there be no mistake: households in 2023 are still paying for the sins of the father, being walloped by the central bank demand hammer to compensate for inflation caused by global currents and the standing water of liquidity poured into the system over the past decade and a half. But it is possible that the hammer can stop whacking sooner than it did 40 years ago – certainly, few expect double-figure interest rates to be a reality in the medium term.

Perhaps it is the case that what we are living through now is just the first inflation shock of a world living under new norms. From 2008 to 2020, every challenge global markets faced was solved –or at least postponed – by the injection of liquidity. Yet inflation disappeared as a threat.

At every turn, observers asked whether and when inflation would be the consequence, and yet for a time it never emerged. Inflation is clearly back in the mix now, however, and it would be foolish to assume it will go away again even if this first skirmish is resolved relatively soon.

As a thought for 2023, I would be somewhat reluctant to assume the correction in credit spreads is quite played out. A more aggressive RBA would likely mean a domestic recession –as is widely assumed to be in the cards for the US and New Zealand in 2023 –and, as is pointed out elsewhere in this issue, recessions rarely fail to come accompanied by wider credit spreads.

Taking a further step back, the ‘megatrend’ seems to me to be the one that has gradually been unfolding since the global financial crisis: household wealth in much of the developed world remains too reliant on recycling and growing debt. The biggest question of all is whether a soft landing is possible when it means revising downward people’s expectations of their prospects for life and lifestyle.