Searching for momentum in transition finance

Finding a way to reliably and meaningfully support environmental transition is perhaps the greatest contribution sustainable finance could make to achieving climate goals – and sustainability-linked bonds have been presented as critical tool for doing so. But flatlining issuance highlights what is perhaps the sector’s greatest challenge to date: how to agree, measure and monitor genuine transition ambition.

Laurence Davison Head of Content KANGANEWS

In at least one respect, the fact that use-of-proceeds (UOP) instruments – specifically green, social and sustainability (GSS) bonds – emerged before sustainability-linked structures and other forms of financing explicitly linked to issuer transition reversed what might appear to be the natural path of decarbonisation. Most borrowing entities, whether public or private sector, need to go through some degree of transition to develop assets suitable for GSS financing.

In other words, GSS bonds and loans might be considered the end state of a transition process. While this form of financing can also be used to build new assets that are green from inception, many borrowers could or should require finance specifically aimed at supporting the transition of their existing processes and assets.

This is where transition-aligned instruments were meant to step in. Two such products are sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) and sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs), which reward borrowers for meeting environmental, social and governance targets, often related to transition. The other is the transition loan or bond, which takes UOP principles and attaches them to assets that deliver transition goals – for instance retrofitting energy transmission networks.

Transition is relevant globally but Asia might be the crucible of change, such is its significance in the region. It was inevitable, therefore, that transition was the central topic of discussion at and around International Capital Market Association (ICMA)’s 9th Annual Conference of the Principles, given the event took place in Singapore.

For instance, speaking at the 28 June conference, Sean Henderson, managing director and co-head of debt capital markets, Asia Pacific, at HSBC, noted that US$3-4 trillion equivalent of finance is needed for energy transition in Asia. There is approximately US$1.8 trillion currently allocated to the sector, of which half is still in fossil fuels. Meanwhile, the Asian GSS bond market is currently roughly US$200 billion.

“There is a huge opportunity to scale up the market, because not enough is being done,” Henderson said. “Asian companies need to do a massive amount of work on transition pathways. My concern is that they will lose access to capital if they don’t do it.”

The impetus to support transition is increasingly apparent. Shinichi Kihara, deputy director general for environmental affairs at Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, noted at the ICMA conference that while hard-to-abate sectors may not be able to define a full path to decarbonisation today, they can commit to ambitious transition strategies that need funding and should be suitable for support from sustainable finance.

The potential impact is clear. “‘Make dirty cleaner’, in fact, is not only important but actually produces the biggest volume of change by 2030,” Kihara said.

Financiers are motivated to direct capital to transition in a way they can measure, accumulate and report. Martijn Hoogerwerf, head of sustainable finance APAC at ING, points out that most banks – including ING – need to drive their loan portfolios toward net zero in order to meet their commitments in this area. Transition finance, including green bonds and sustainability linked loans, is one of the primary means by which they do so.

TRANSITION STALLED

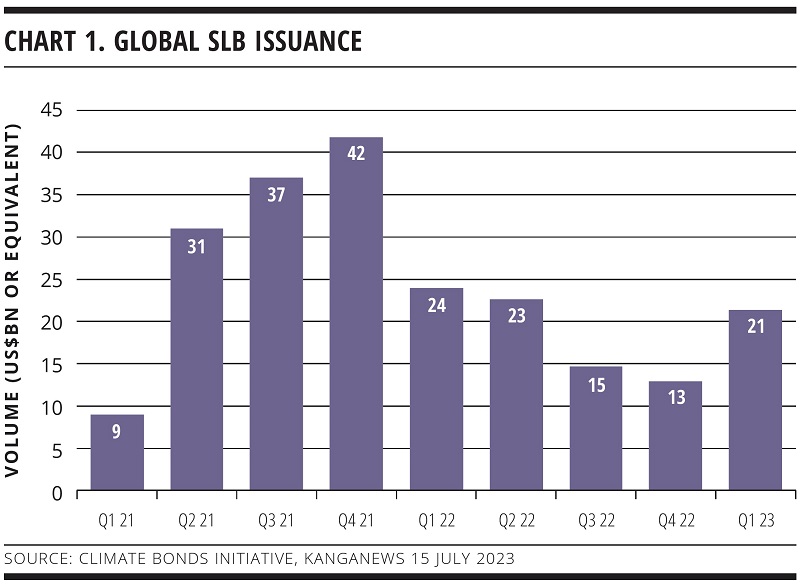

Labelled products used to finance transition offered early promise. SLLs were very much in vogue either side of the start of the current decade and in 2021 it seemed SLBs were set to join them. However, far from enjoying exponential growth, issuance has slowed: according to Climate Bonds Initiative data, SLB supply was more than 30 per cent down in 2022 compared with the previous year (see chart 1). Meanwhile, transition bonds remain a fringe asset class mainly issued by Japanese borrowers.

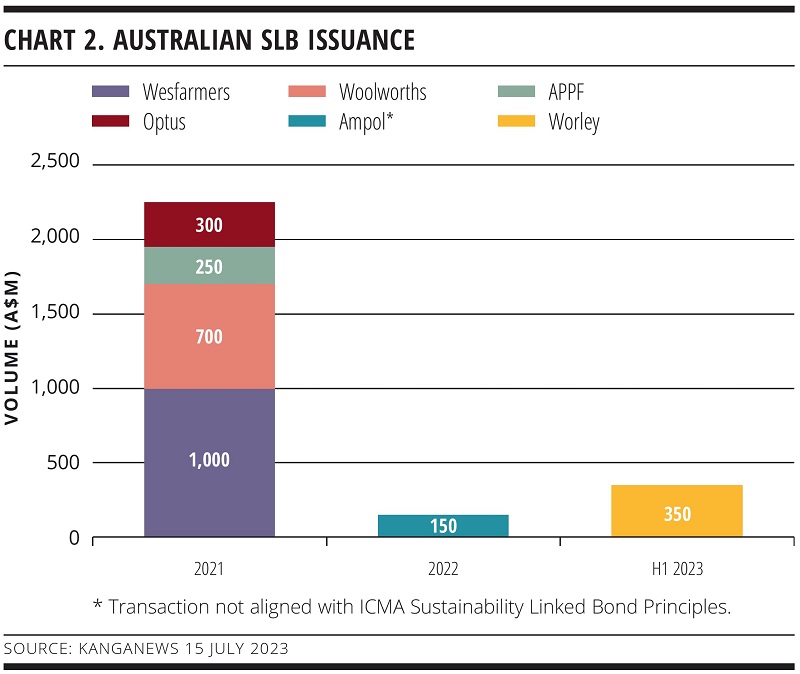

The same issuance profile is apparent in Australia, albeit in microcosm. SLB supply got off to a promising start in 2021, with four deals coming to market including transactions from some blue chip local corporate names (see chart 2). But the asset class did not build on this early momentum and there have been just two transactions since – and no transition bonds.

The market-wide slump in true-corporate issuance is no doubt partly to blame, but neither issuers nor investors appear to have overwhelming demand for SLB deals. The problem, market users say, is the relative difficulty of agreeing a measurable, comparable definition of acceptable ambition in transition. As Henderson said at the Singapore conference: “Doing a green bond is relatively easy nowadays: there are a number of taxonomies in use and it is fairly straightforward to align assets with these. On sustainability-linked, we may have defined what is good but not how quickly we need to get there.”

The definition of good falls to initiatives like ICMA’s SLB Principles (SLBPs) and the supporting Climate Transition Finance Handbook. These ask issuers to select KPIs that are “relevant, core and material to the corporate issuer’s overall business” with sustainability performance targets that “represent a material improvement in the respective KPIs and be beyond a ‘business as usual’ trajectory”. The SLBPs also ask for targets to be measurable or quantifiable, externally verifiable and able to be benchmarked.

Market participants agree that the SLBPs provide a sound outline for what SLBs should be seeking to achieve. The challenge lies in what comes next. Henderson’s point is that issuers are able to use taxonomy alignment to demonstrate how the assets they are financing with GSS bonds satisfy the Green Bond Principles, Social Bond Principles and Sustainability Bond Guidelines but there is no agreed taxonomy for transition ambition.

Into this gap can slide the unambitious and the greenwasher, and even transition that leads to an emissions reduction dead end (see box). Eila Kreivi, chief sustainable finance advisor at European Investment Bank, tells KangaNews: “A good way to look at transition is to imagine three bands – red, amber and green. In the red band are companies that have the furthest to go to reach green. Many SLBs have come from companies that are in the red band and are only moving within the same band – they are not ambitious enough, in other words. I am talking about things like an oil company issuing an SLB that exclusively focuses on its scope-one emissions.”

Locking out the lock-in

The concept of locked-in emissions provides a perfect example of the pitfalls of transition finance. This is where an apparently positive step in emissions reduction actually leaves the issuer tied to an imperfect interim position in a way that precludes necessary further improvement in future.

For instance, an electricity generator replacing coal-fired power with natural gas would reduce emissions in the near term. But it would likely not be considered an ambitious transition if the gas-fired asset has a 30-year lifespan during which time it cannot be replaced by renewables.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) guidance on transition finance supports the view that “corporates can and should pursue a multitechnology approach to mitigation”, and specifically that the industrial sector “will require a portfolio of solutions, ranging from energy efficiency improvements in production processes, shifting the power and heat supply from fossil fuels to renewables and renewables-based electrification, switching to low-carbon and renewable feed stocks, and deploying carbon capture use and storage, to increasing the reuse and recycling of materials”.

However, equally important is the context that “it will be essential to avoid investments in emission reduction opportunities that have the effect of locking in emissions”. The OECD says will slow down the adoption of net zero alternatives and result in assets having to be replaced before the end of their natural lifespan.

The flip side of the same coin is that the uncertainty about what qualifies as ambition is leading companies to shy away from putting their business on the street in the form of publicly disclosed SLB targets.

Christa Clapp, managing director, sustainable finance at Shades of Green, observes: “There are some interesting – arguably conflicting – trends in transition finance. It is clearly needed – perhaps even more so than ‘dark green’. But there seems to be some reluctance on the part of companies to issue transition instruments or even to be considered as transition businesses.”

Wariness is not just on the issuer side. Investors, too, are concerned about the risk of being seen to endorse transition that turns out to be insufficiently ambitious. Further, some asset managers argue that the lack of common language on what constitutes ambition makes the whole concept of transition finance too nebulous to put in front of their clients.

Bram Bos, managing director at Goldman Sachs Asset Management, told delegates at the ICMA conference: “Our clients can understand UOP bonds but they struggle to understand SLBs; it is a complex concept. This is a major factor, and it has led us to leave SLBs out of our ESG labelled products – they are just too hard to explain to clients.”

The level of concern about the SLB asset class is close to existential for some market users. Bos added: “Something has to be done to evolve SLBs in a positive way because, at present, they are so unclearly defined there is a genuine risk that they will not exist in five years’ time. Issuance has already slumped and the financial sector is not participating at all. We all like the concept, but we have not found a good answer to the question of how we make it work.”

THE WAY FORWARD

Most are not ready to give up on sustainability-linked instruments as a means of delivering transition finance. For one thing, the scale of capital needed to support transition means every available tool may be required.

While the SLB issuance slowdown may be disappointing, especially as it has been driven at least in part by skepticism about the product’s efficacy, others say it is important to remember that sustainability-linked financing is still in its early days and setbacks do not have to be fatal.

“If GSS bonds are in the teenage phase, the SLB is a toddler,” Rahul Ghosh, managing director, sustainable finance at Moody’s Investors Service, said at the Singapore event. “It is good that the focus seems to be on quality rather than quantity – it means the market is learning. The issues we have to deal with are in the detail: things like the means by which targets are achieved, including the use of offsets.”

A lot of hope is being invested in the development of more sophisticated reporting tools, on the basis that quantifiable transition trajectories will make it easier to compare issuers’ ambition and progress. Developments like rigorous climate-related disclosure delivered by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) – which published its first two global sustainability disclosure standards in Singapore the day before the ICMA event – will provide the tools for comparing transition ambition.

Progress is already being made. Singapore is trying to build a world-leading market ecosystem for sustainable finance that builds on developments like the ISSB standards and EU sustainable finance taxonomy (see box). Hoogerwerf points to the industry-wide and market accepted decarbonisation net zero pathway developed in the shipping sector as a good basis for mapping client trajectories – though he also acknowledges that few industries have this.

Singapore takes the lead on transition

While the EU’s sustainable finance taxonomy elected not to address transition finance directly, Singapore’s equivalent tackles this tricky topic. The city state’s financial market infrastructure providers and policymakers are also attempting to nurture a supportive environment.

The desire to support transition comes from the top. Speaking at the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) conference, Indranee Rajah, minister in the Singapore prime minister’s office and second minister for finance and national development, said: “Pure green activities make up only about 8 per cent of the global economy. We need to do more, and we need to speed up… To get there, we will need transition finance.”

Rajah noted that most global taxonomies focus on green assets, leaving the market without standardised definitions of what can be credibly considered transition – an important step to further lowering the barriers to entry for private capital.

Singapore’s Green and Transition Taxonomy is organised according to a traffic light system similar to colour coding in the ASEAN taxonomy. Under this system, an economic activity can be classified as green, amber or red.

“Mandatory reporting standards are improving,” Rahul Sheth, Standard Chartered’s global head of sustainable bonds, said at the ICMA conference. “They are an important component of self-discipline and provide good checks on issuer progress on a transition strategy.”

As reporting and comparability emerges, it will be vital for issuers not to hide from transparency. For instance, Isabelle Laurent, deputy treasurer at European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and chair of the International Capital Market Association Principles executive committee, said: “We should welcome rather than recoil in horror from missed KPIs. It represents the market doing exactly what it should: it speaks to stretching the level of ambition rather than targets that are easy or that are already almost reached when the financing is secured.”

It may be that the instruments available to support transition via debt finance do not in and of themselves require a radical overhaul – just the development of supporting infrastructure sufficient to make all sides of the market confident in their deployment. Plenty of market participants – likely even a majority – still have fundamental faith in the SLB, for instance.

Henderson said: “My sense is that the market will develop confidence with SLBs once we have strong enough definitions of ambition and trajectories.”

Sheth went even further, commenting: “All the characteristics needed for sustainable finance are already part of SLBs – it is all there from the perspective of the usability of the label.”

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.

SSA Yearbook 2023

The annual guide to the world's most significant supranational, sovereign and agency sector issuers.