The nitty gritty of fixed-income investors' ESG engagement and demand

Each year, Commonwealth Bank of Australia and KangaNews survey Australian fixed-income asset managers to get an update on the lay of the land in local sustainable capital markets, then invite investors to add qualitative thoughts to the data at a roundtable discussion. The 2023 outcome paints a picture of a market that continues to mature but still has a number of hurdles to clear.

Helen Craig Head of Operations KANGANEWS

Laurence Davison Head of Content KANGANEWS

Once again, more than 35 Australian fixed-income investors, representing fixed-income assets under management (AUM) of approximately A$800 billion (US$510.4 billion), filled in a survey that KangaNews conducted in August. The majority – 60 per cent – of responses came from institutional fund managers with the balance comprising a relatively even mix of insurance, superannuation and retail funds, and others. The roundtable discussion followed in mid-September, when Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) and KangaNews brought together half a dozen investors to talk through the survey results in detail.

The survey is aimed at all fixed-income investors: specialist environmental, social and governance (ESG) or impact investors can and do respond, but the bulk of the data comes from mainstream vanilla funds.

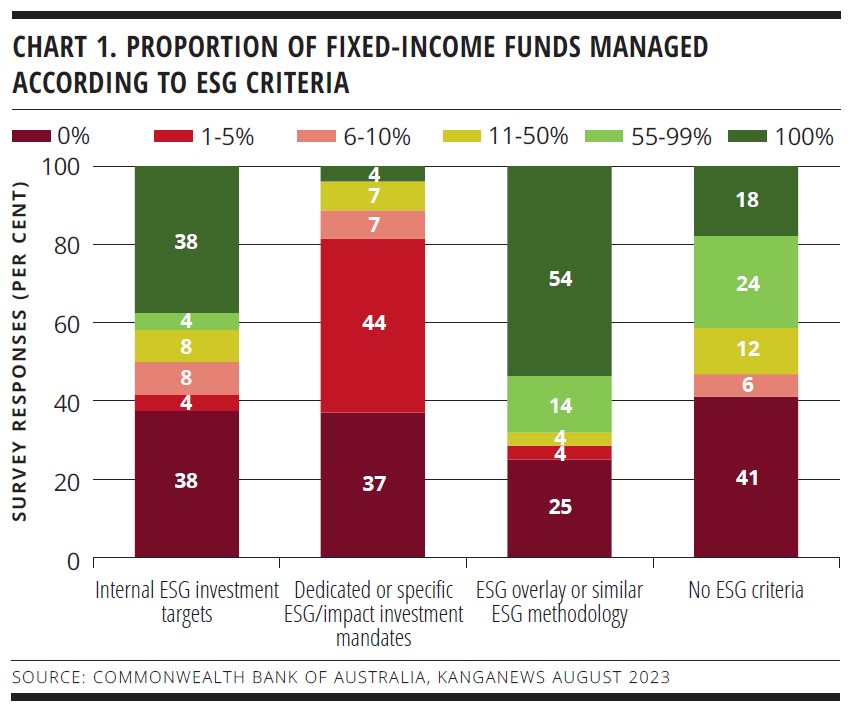

Responses to questions on mandates back the claim that ESG considerations are increasingly integrated into investment decisions. More than half the survey respondents say all their AUM have an ESG overlay or equivalent while 63 per cent of respondents manage at least a portion of AUM in dedicated ESG funds or mandates (see chart 1). There is no obvious sign of a wide-scale proliferation of dedicated mandates, however: more than 80 per cent of respondents have no more than 10 per cent of their AUM in this format.

Adrian David, division director at Macquarie Asset Management in Sydney, suggests ESG adoption reflects a fundamental shift in end-investor preferences that only a few are not embracing. “Everyone still cares about alpha but it is no longer the full story,” David explains. “While some clients are only focused on returns, there is a growing desire to embed emissions reduction in portfolios. Some of our clients are really closely focused on it: they might ask us, for instance, why we sold a bank and bought a transmission company if doing so increased portfolio emissions. There is a lot of dialogue about these issues nowadays.”

“We have all become accustomed to credit ratings and the methodologies behind them, and I think there had been some expectation that, in time, we would get an equivalent type of score for ESG. But we are starting to understand that this is such a complex area that it might not be so straightforward.”

What the survey data most likely reflect is different speeds and levels of sophistication among end clients. Ben Squire, executive director and head of credit research, Asia Pacific at UBS Asset Management in Sydney, agrees that clients are, in general, demanding more focus on ESG.

But he adds: “The issue may be that, in some cases, they are still trying to work out what they themselves want. We are trying to have two-way dialogue to help them on the path. The insurance sector is leading because of its awareness of risk on both sides of the balance sheet, but it is also a developing theme with superannuation funds. It is happening – but it still feels like early days.”

Investors at the roundtable are therefore not surprised that dedicated ESG funds have not overtaken more broad-based ESG integration. Lucie Bielczykova, Sydney-based portfolio manager at Revolution Asset Management, says ESG focused funds “are becoming confined to the impact or thematic investment space” while even the most ESG-engaged client type – superannuation and insurance funds – want to tailor their mandates to ESG considerations but not exclusively so.

Other influences are likely at play, too. One is the growing buy-side awareness of greenwashing, which may be leading investors to be wary of making claims about the sustainability credentials of their funds (see box). Meanwhile, 2022’s fixed-income rout may have been particularly hard hitting in the ESG space. Kylie-Anne Richards, deputy chief investment officer at Fortlake Asset Management in Sydney, notes: “Because of the relatively poor performance of thematic fixed-income funds in 2022, I suspect some investors are stepping back from the space. I expect – or I certainly hope – this will change over the next couple of years.”

Overall, however, ESG is increasingly mainstream: nearly 40 per cent of fund managers apply “internal ESG investment targets” to all their AUM. Squire reveals: “We look at ESG for every company, whether or not our clients ask for it. This is because there may be material risk or technical implications for the way the issuer’s bonds are priced or trade. Even if a client isn’t interested in ESG, the bonds it is investing in can be influenced by it.”

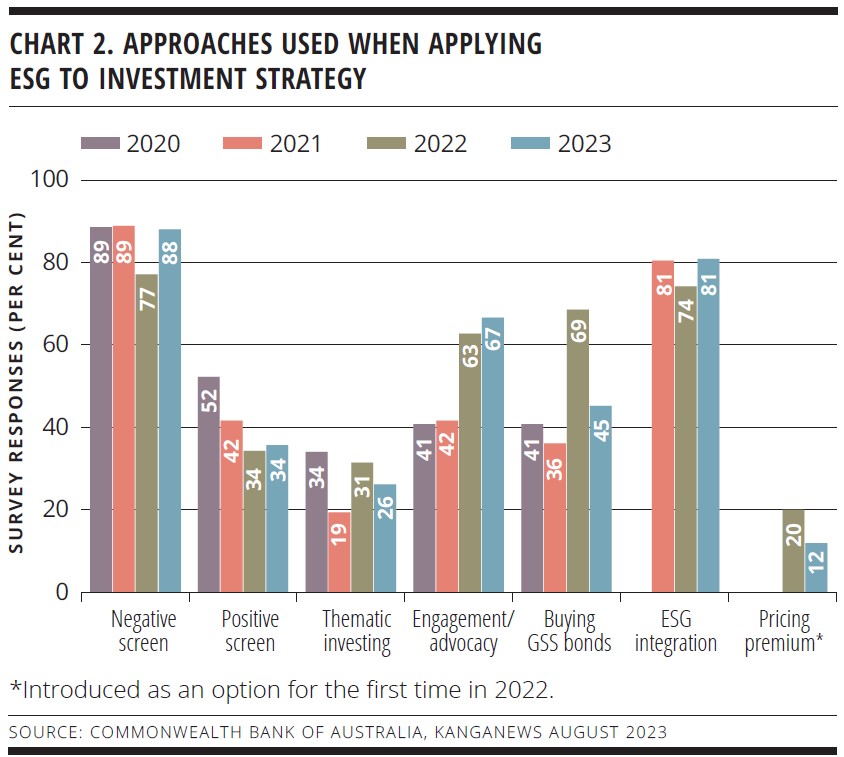

The varying level of client sophistication is further demonstrated by the ongoing prevalence of the negative screen as the most common approach used in ESG deployment. After dipping slightly in the 2022 survey, in 2023 nearly 90 per cent of investors responding to the CBA-KangaNews survey report the use of negative screening (see chart 2). ESG integration is also popular, and the use of engagement and advocacy continues to grow.

INVESTORS SEEK TO GET AHEAD OF GREENWASHING RISK

Greenwashing has become a focus of regulatory and media attention in Australia in recent times, with the investment community well and truly in the crosshairs. Fixed-income investors report an elevated – but manageable – degree of concern.

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA)-KangaNews survey suggests nearly three-quarters of investors are currently at least somewhat concerned about greenwashing risk in the sustainable finance market as a whole (see chart).

The large majority of these responses are only “somewhat” concerned, however. Investors also seem to be confident in their own ESG analysis: while 60 per cent of survey respondents express concern about greenwashing in securities they have not bought, only half as many extend this concern to their own holdings.

Investors acknowledge that exclusion is still an important part Of many end clients’ thinking and in some cases forms the entirety of their ESG approach. It also tends to be the first step into ESG – and many end investors are still at this stage. Taken together, these factors mean that, overall, exclusions are increasing rather than being replaced by more sophisticated approaches.

“The client focus is typically exclusionary, accompanied by ever-more focus on emissions – specifically net zero emissions,” Squire confirms. “The challenge is that transition by really dirty companies is where we will get the biggest change in emissions globally and make the most positive difference to the world. This is what we need to convince our clients about – but it is a slow-moving process.”

At this stage in the development of Australian sustainable finance, stewards of the bulk of investment funds do not appear to have fully engaged with the needs of financing transition. Investors at the roundtable point out that exclusion alone is likely to produce worse outcomes, by allowing the most polluting or hard to abate assets to be acquired, at a discount, by parties with little or no interest in pursuing transition.

"A big chunk of Australian corporate bond issuance comes from privately owned borrowers and, even when the owners are high-credentialled funds, the disclosure we get can be lacking. We always say to companies that we want to spend our time understanding their business rather than just trying to get information about it.”

Squire adds: “There is an education component to the advocacy and transition approach but I admit it can be challenging. It’s not that our clients don’t want to do transition, but as a first step it’s possibly easier for them to go down the exclusionary path and take the benefit of initial, relatively easy step-changes in their emissions profile.”

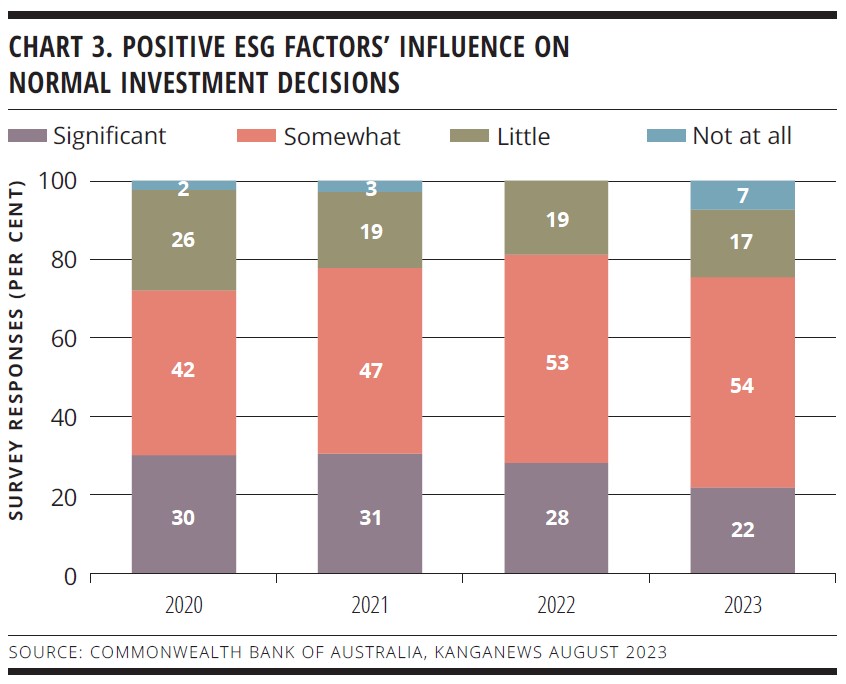

This may go some way toward explaining why positive ESG factors only have a limited impact on fixed-income investors’ normal credit decisions. The proportion of investors reporting a “significant” influence from ESG on the positive side has actually fallen over the four years that CBA and KangaNews have conducted their survey, although more than half of investors consistently say it has “somewhat” of an impact (see chart 3).

Gus Medeiros, CBA’s Sydney-based head of credit strategy, Suggests there may be room for even further integration of ESG risk and credit risk. He explains: “If a company has an operational edge associated with emissions reduction it could become a competitive advantage that may be interpreted as a creditworthiness edge – if the company is able to reduce ESG operational risks or demonstrate a stronger emissions glidepath relative to comparable issuers. This could contribute to better relative credit pricing for the issuer.”

Bielczykova agrees that ESG risk is a component of overall credit risk. But she also notes constraints on the ability of debt Investors to consider it as a positive factor. “We are never going to invest in a company that is great from an ESG perspective but which is losing money and we do not think has realistic prospects of ever doing well,” she comments. “Meanwhile, because our upside is limited we are naturally focused on bad outcomes and how we can mitigate them.”

REPORTING AND DATA

The growing focus on understanding ESG risk as credit risk and evolving client demand are driving a need for more and better data disclosure and analysis. But they are not the only reasons why data is perhaps the most important single component of sustainable finance evolution at present. Mandatory climate risk reporting is coming, which will require significant investment in systems and capability.

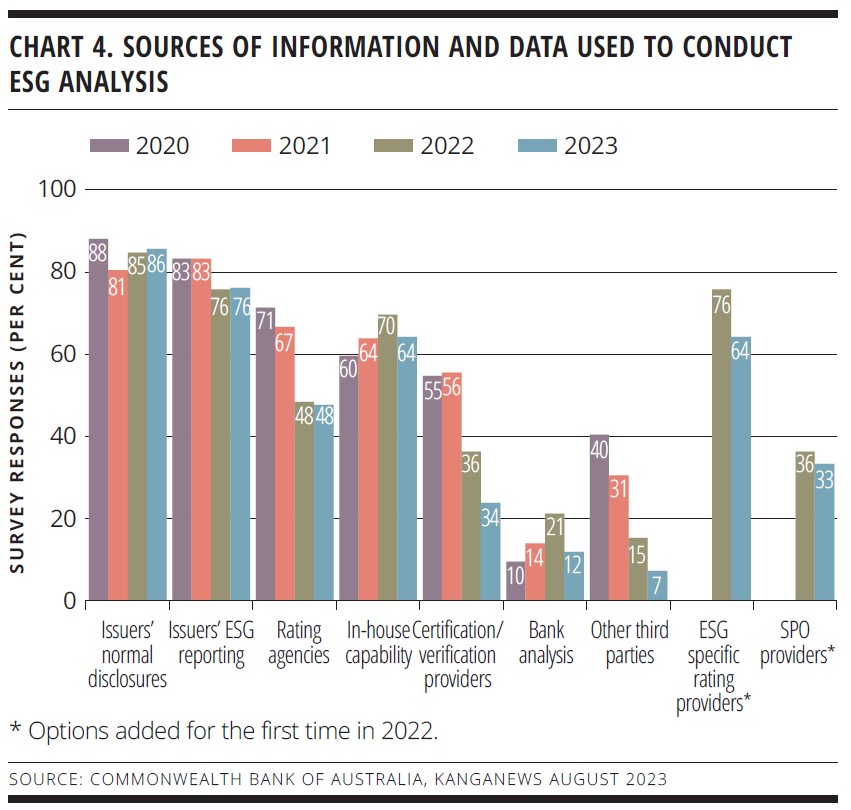

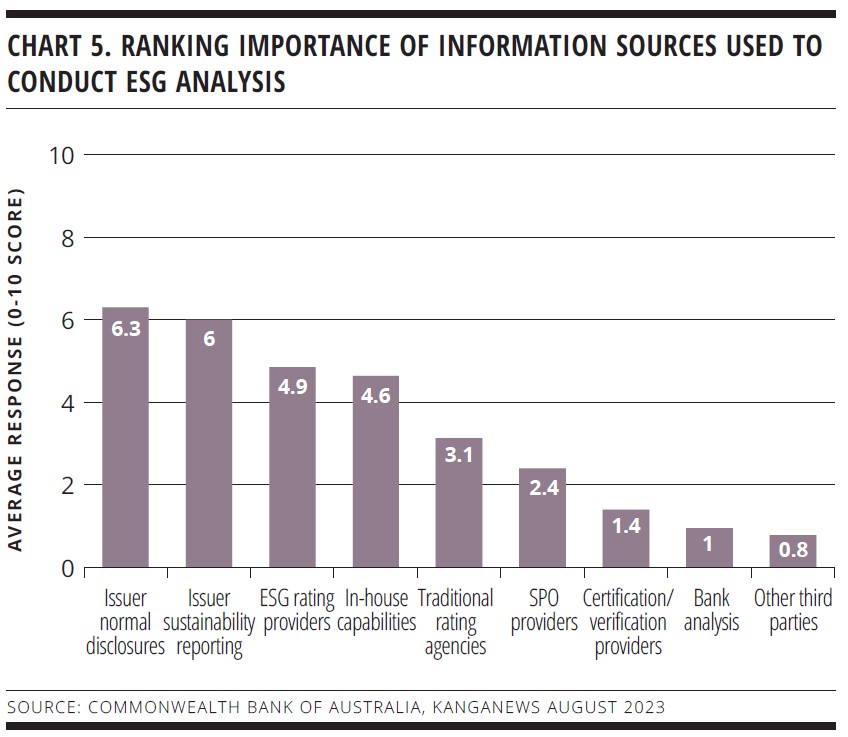

Investor preferences are clearly migrating toward a focus on data that comes direct from the source and on their own capabilities, rather than reliance on third-party providers. Investors’ use of ESG data provided by mainstream credit rating agencies or by certification and verification providers has fallen in the last two iterations of the CBA-KangaNews survey, while bank analysis and second-party opinion (SPO) providers have only ever been used by a minority of investors (see charts 4 and 5).

The buy side reports more interest in ESG-specific ratings but even here usage has fallen, perhaps because they are typically used to supplement rather than replace in-house analysis.

The clear preference is for issuers’ own data – whether provided in normal disclosures or as part of ESG-specific reporting – which investors can conduct their own analysis upon. David says: “We love source documents so we want to go straight to the companies themselves. We expect all issuers to be producing public sustainability or ESG reports.”

Charles Davis, CBA’s Sydney-based managing director, sustainable finance, suggests: “There is an absolute desire for more consistency of external data and information but this is a highly complex and nuanced area. We have all become accustomed to credit ratings and the methodologies behind them, and I think there had been some expectation that, in time, we would get an equivalent type of score for ESG. But we are starting to understand that this is such a complex area that it might not be so straightforward.”

Patricia Gacis, Sydney-based senior credit analyst at First Sentier Investors, adds: “There is a place for standardisation but the reality is that the transition pathway for one sector will be very different from another. In this context it is no surprise that we are all still grappling with what data we should be recording and what targets we should be setting. It will be very helpful if we get a local taxonomy sooner rather than later.”

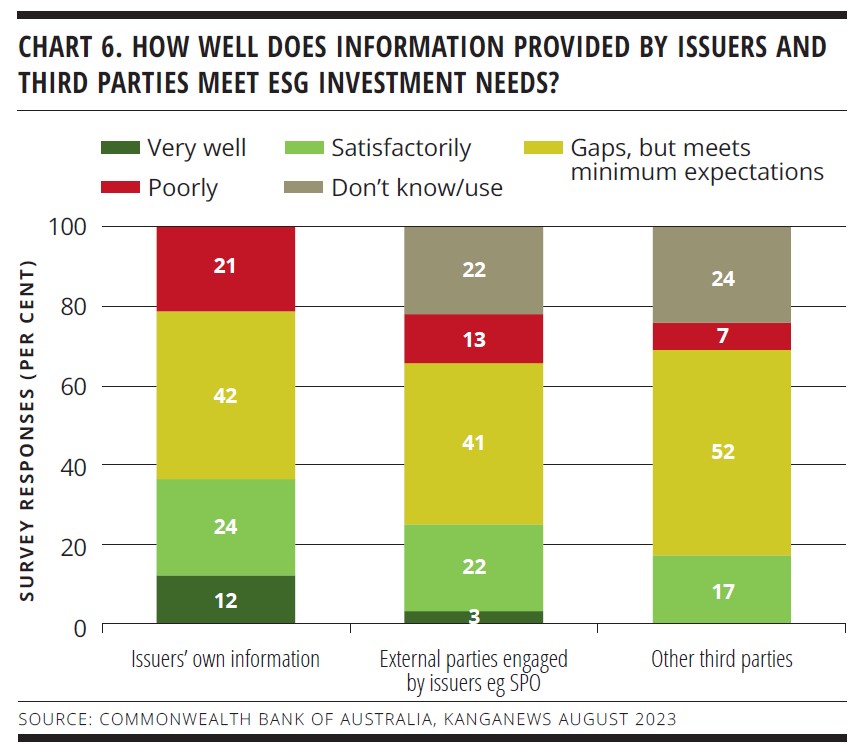

The development of an Australian sustainable finance taxonomy could also help deal with another issue the CBA-KangaNews survey highlights: that investors are far from fully satisfied with the information they receive, even when it comes direct from issuers. Nearly two-thirds of survey respondents suggest issuer data generally has, at least, gaps – including more than 20 per cent that rate it as outright unsatisfactory (see chart 6). Data from external providers is no more reliable, investors say.

David says: “A big chunk of Australian corporate bond issuance comes from privately owned borrowers and, even when the owners are high-credentialled funds, the disclosure we get can be lacking. We always say to companies that we want to spend our time understanding their business rather than just trying to get information about it, and we always prefer to go to the source document where possible.”

Richards adds: “There are several thousand potential ESG variables, yet the data sets have significant gaps, varied time frequencies and inaccuracies. If we apply standard models we will not get meaningful information.”

The situation is likely even more challenging in the private debt space. Bielczykova explains that the sector lends itself to advocacy and engagement approaches because access to management is typically part and parcel of lending arrangements. But this work is often qualitative in nature because there is very little available data. “There are rarely credit ratings, let alone ESG ratings, on the loans and the borrowers we deal with,” Bielczykova confirms.

Data provision by issuers and third parties may improve symbiotically. Lauren Holtsbaum, head of ESG DCM origination at CBA in Sydney, says many issuers are making a concerted effort to make more information publicly available in preparation for mandatory climate reporting and to satisfy stakeholders including rating agencies. ESG rating providers rely on publicly available data – and if an issuer is not providing this data on a public platfom its rating may not accurately reflect its ESG credentials.

Having a sustainable finance taxonomy in place should help standardise many aspects of data provision, potentially easing the resource burden on issuers. Davis believes Australia’s forthcoming taxonomy will help provide a common standard and a credible framework to guide the allocation of capital. Mandatory climate risk reporting, meanwhile, should help bring data laggards up to at least a minimum standard of disclosure.

ACCESS TO CAPITAL

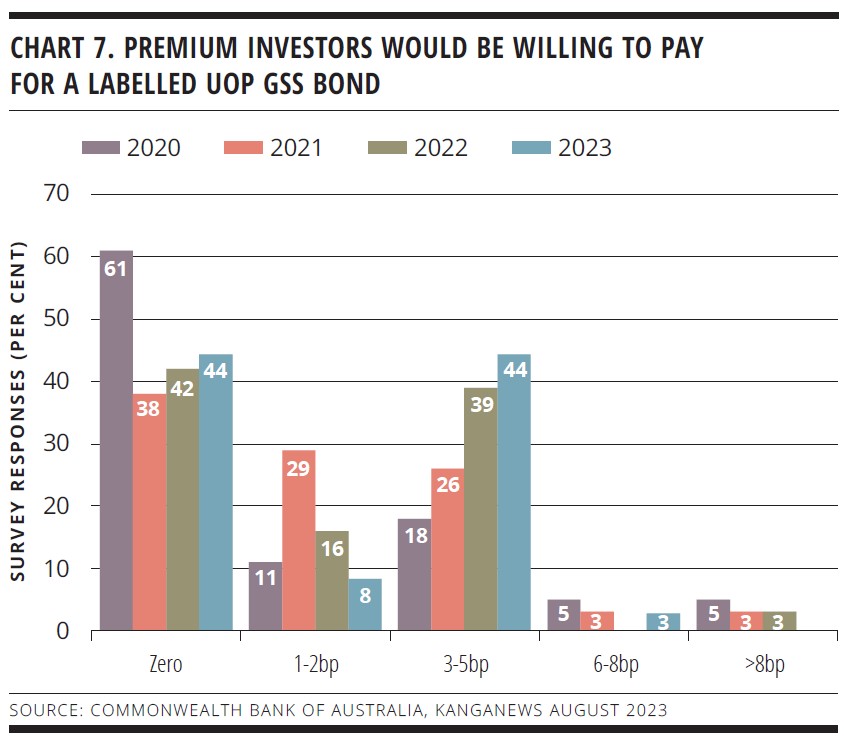

Overall, the survey and investor commentary suggest there is a divergence in opinion on the ‘greenium’ attached to labelled bonds. More than half of respondents would be willing to pay a premium, the majority of these in the 3-5 basis points range (see chart 7). CBA believes the willingness to offer a premium is likely to be driven by ESG mandates that support a buy-and-hold strategy, while those not willing to pay more are likely to be general funds that are more return focused.

There is a relatively stable level of willingness to pay a greenium for labelled use-of-proceeds (UOP) green, social and sustainability bonds. The proportion of investors that will not do so fell significantly between the 2020 and 2021 surveys, and while it has climbed slightly since it remains well below the 2020 level.

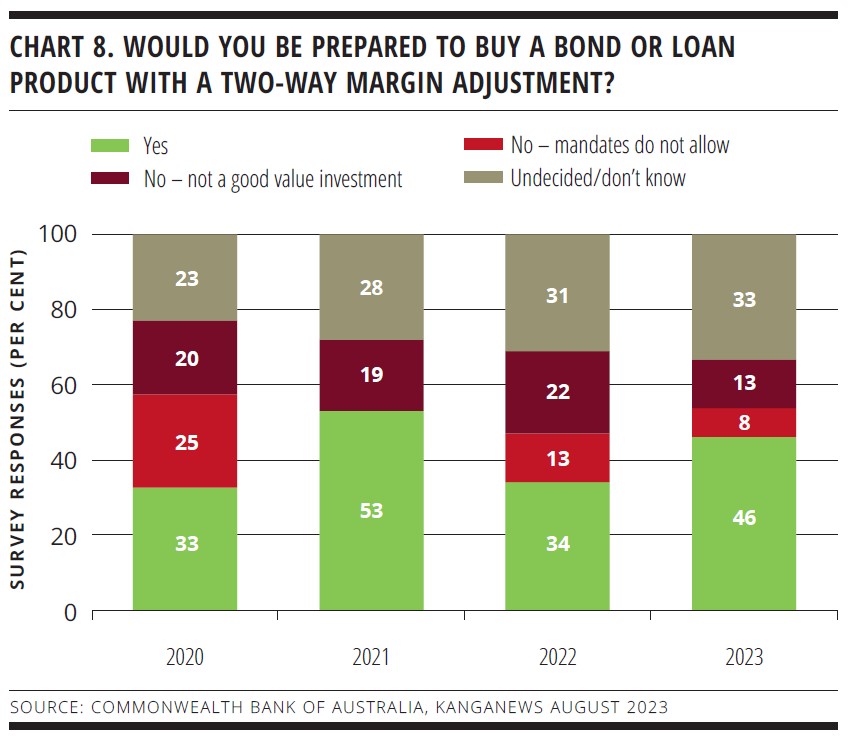

Almost half of investors are willing to support two-way coupon adjustments for sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs), up from 2022 and broadly in line with 2021 (see chart 8). In addition, the number of investors outright rejecting the concept n the basis that it is not a good investment has fallen, suggesting the buy side is open to the concept where it incentivises outcomes.

There is still a good level of in-principle support for SLBs. David says: “There are some companies that ordinarily we would not want to invest in, because the carbon risks are too high or the transition is going to be beyond what we think they can deal with. But if such a company came out with a transition product that, in our view, addressed the risks we perceive in its business or the way it operates, this could allow it to become a name we will invest in. We believe it is possible for risks we identify through our ESG process to be addressed through a product.”

The challenge lies in delivering a transition-aligned product that all sides can agree reflects an ambitious decarbonisation pathway. Doing so has proved easier in the loan market, but Gacis explains: “The loan market is easier because of the relatively small number of investors involved. A step-up and step-down SLB mechanism is hard because it is difficult to get a consensus among a large number of bond investors about what they want in an instrument.”

There is clearly a lot of work still to be done. Davis adds: “The key question is how we define credibility in transition. This starts with what decarbonisation pathway an issuer is going down but there are layers of nuance to it – it’s possible to keep digging deeper and deeper. I don’t feel we have yet coalesced around consistent themes in this respect.”

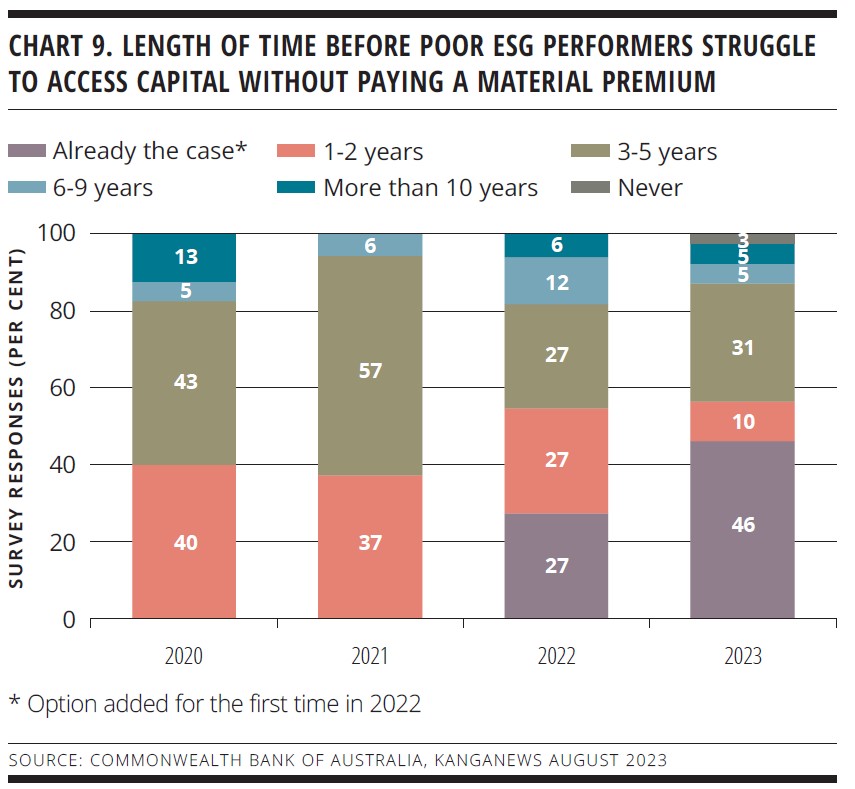

On the other hand, Australian investors are much more confident that poor ESG performers are already incurring elevated cost of funds to the extent that there is a material impact on access to capital. Nearly half of survey respondents believe this is already the case and most of the rest believe it will become so within the next five years (see chart 9).

This response matches Medeiros’s analysis, which breaks the Australian corporate bond market down into higher-emission issuers, vanilla issuers and ESG labelled bond issuers. He says there is a growing relative discount or widening of spreads for the higher-emission entities, even relative to early 2023.

“The market is becoming more aware of ESG costs, which gives investors a greater opportunity to explore transition as well as an incentive for issuers to reduce the relative discount,” Medeiros concludes.

Investors at the roundtable agree. “We are certainly witnessing a pricing differential emerging for higher-emitting borrowers – and it is also leading to changes in behaviour,” Gacis says. “This could mean increasing the volume of recyclables in its products or introducing new targets. Capital market pricing is undoubtedly driving change.”

The phenomenon extends beyond the investment-grade sector, too. Bielczykova notes “very material differences” in pricing even within sectors in the private debt market. As an example, she points to a recent transport company deal where a significant proportion of the borrower’s clients were miners and the collateral was things like trucks that have been purpose built for coal transportation. The deal priced materially wider than otherwise comparable leveraged loans and where the market would be for a transport company without the underlying exposure to mining.

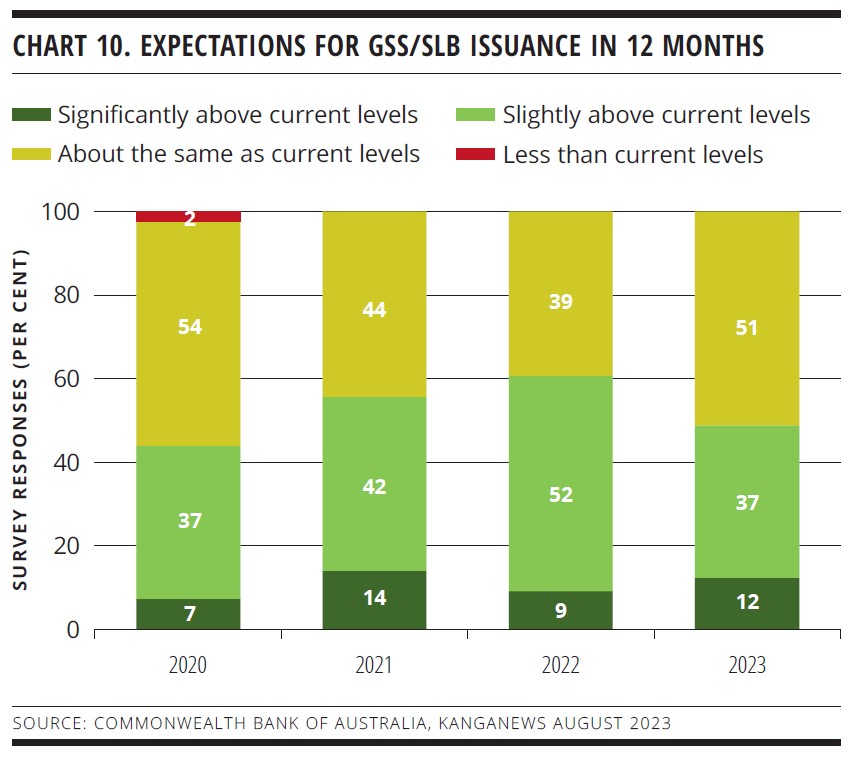

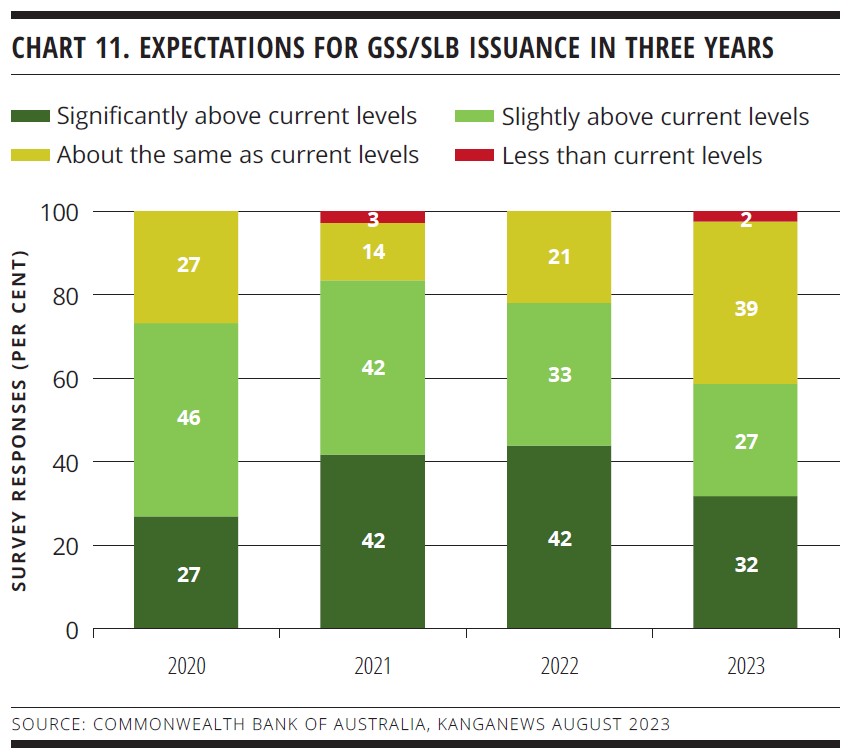

The data all appear to be pointing in one direction: that the integration of ESG analysis in the mainstream credit process is well underway, even if it has some way to go to reach full maturity. In this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that expectations on the outlook for labelled securities – whether in UOP or SLB format – are of gradual rather than exponential growth in supply.

Almost no survey respondents anticipate a reduction in issuance, while nearly half expect it to grow in the next 12 months and nearly 60 per cent in the next three years (see charts 10 and 11). But while just 12 per cent of survey respondents forecast a “significant” increase in labelled supply in the coming year, this number jumps to 32 per cent over a three-year horizon.

"Some issuers are questioning whether they should be issuing labelled securities or just coming to market in vanilla format and promoting their positive ESG credentials. If the issuer has resource or capacity constraints to maintain a labelled programme, the vanilla path can make more sense at a particular point in time.”

Investors suspect further growth in issuance of labelled product will be limited by supply-side factors rather than lack of demand. “There is certainly demand out there for labelled bonds,” Richards insists. “SLBs are a little more challenging, although they offer incentives for issuers and investors and I certainly think they are a great product.”

Jo Lyn Tan, executive director, ESG DCM at CBA in Sydney, comments: “Having capacity to source quality data and commit to additional reporting is a challenge for issuers considering whether to issue labelled bonds. I suspect this will mean some struggle to justify the cost. It would be great if there were more support mechanisms or tools.”

Tan points to the Singapore government’s scheme that makes grants to cover the cost of external reviews available to issuers as the type of support that might facilitate labelled bond issuance in Australia.

She adds: “There is scope for further development in transition financing. Considering the scale and pace of investment needed to address the climate crisis, there is a significant opportunity to deliver both returns and impact.”

In the meantime, Holtsbaum says: “Some issuers are questioning whether they should be issuing labelled securities or just coming to market in vanilla format and promoting their positive ESG credentials. If the issuer has resource or capacity constraints to maintain a labelled programme, the vanilla path can make more sense at a particular point in time. This discussion will continue as the ESG market evolves, and I don’t think every issuer will come to the same conclusion.”

Some issuers opt to convey a strong signal to the market regarding their ESG commitments and ambition, Holtsbaum continues. This is the case particularly for companies with well-defined top-down sustainability strategies and which want to align financing with their overall approach. In this case, the issuer may consider resourcing a labelled transaction to be a part of its everyday operations.

While volume may not have exploded, investors are generally pleased with the way labelled product has evolved. David suggests some of Australia’s first green-bond issuers had very good green credentials but, on occasion, were not as strong on social or governance areas. But he adds: “Since the pandemic, the labelled market has matured with more issuance from a wider range of companies. This provided more choice, so we were able to buy some deals while still avoiding those that were strong in one area but weak elsewhere.”

"If a company has an operational edge associated with emissions reduction it could become a competitive advantage that may be interpreted as a creditworthiness edge – if the company is able to reduce ESG operational risks or demonstrate a stronger emissions glidepath relative to comparable issuers.”

In general, investors believe labelled product has a role but are wary of giving it a universal green light. Gacis explains: “I believe labelled bonds have a place until transition is complete – and this is going to take some time. We will continue to see, and support, this type of issuance for the foreseeable future. On the other hand, not all green-bond issuance is the same and we will have to analyse each and every one that comes to market.”

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2023

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.